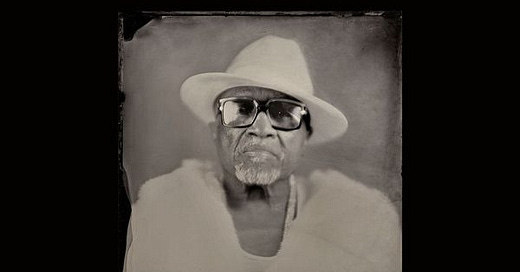

Swamp Dogg - Blackgrass

Charles on a fantastic new album from a true original, with thoughts from the man himself

(This is part 2 of Swamp Dogg Week. I earlier talked about 16 songs that I love from earlier in his career, and you can read that here.)

In her masterful recent book My Black Country, Alice Randall describes Swamp Dogg as an enduring symbol of “Black Country eccentricity.” For Randall, these “eccentrics of Black Country refuse to be seduced into a false sense of belonging achieved by adhering to established codes of aesthetics arising from either their home communities or the dominant culture.” Additionally, they “exploit the reality that Country is a hybrid form that draws from African, European, and Indigenous American influences. A global feast of myth, iconic stories, and elemental archetypes is offered up in their songs and life stories.”

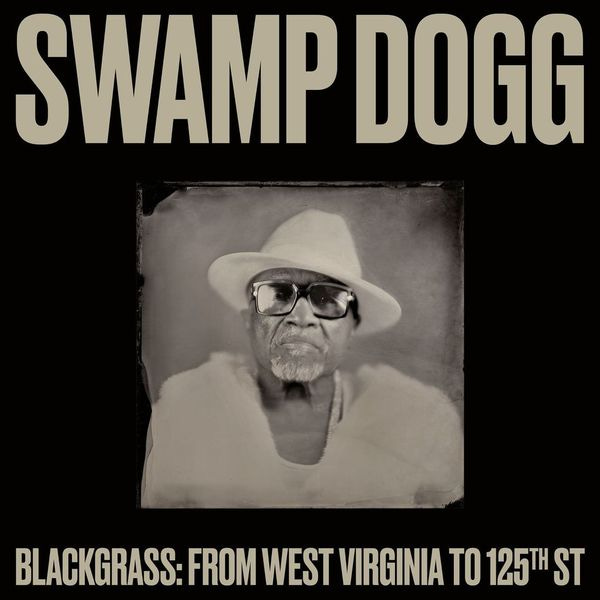

It's hard to imagine a better description of Swamp Dogg’s wild and wonderful career, now in its seventh decade. His new album, Blackgrass: From West Virginia to 125th Street, adds yet another chapter to that still-expanding legacy. It finds this musical explorer heading in another new stylistic direction while reaffirming the roads that brought him here. From its Afro-centric, migration-minded title through material ranging from songs he loved as a kid to new material written with younger collaborators, Blackgrass claims space outside and alongside the boundaries that Jerry Williams, Jr. – as Swamp Dogg or otherwise – has traversed and transgressed as he’s forged his own iconoclastic path.

First thing’s first: Swamp Dogg has always been country, and his career has been marked by both the possibilities and limitations of this most racialized musical genre. It was the first music he heard growing up on radio and recordings. The first song he sang in public was a talent-show take on Red Foley’s version of “Peace in the Valley”; he followed that up with a performance of Bill Nettles’ “Hadacol Boogie.” His work as a songwriter included “She’s All I Got,” a pop and R&B hit for Freddie North that became a country smash when recorded by Johnny Paycheck in 1971. Still, when Williams and his co-writer Gary Anderson (a.k.a. Gary “U.S.” Bonds) won that year’s BMI Song of the Year Award, they somehow weren’t invited to the award ceremony, an omission that he recalled long afterwards.

That same year, he crossed paths with the one Black performer to attain superstar status in country in that era. “I had tears in my eyes shaking Charley Pride’s hand,” he told me in a recent Zoom interview. “Meeting a real country star. I think my eyes watered up because he was Black, and he was at the top. The very top.” But Pride’s success didn’t mean that the doors swung open more widely, a fact that Williams recalled to me with characteristic bluntness: “They always let one succeed,” he told me in 2009. “They let a black guy in to sing country, and the motherfucker went all the way to the top. And they’re like, ‘We’re not letting any more of these cocksuckers in.’” Even with his BMI award and Paycheck paychecks, and despite making such great and gloriously “eccentric” music, Jerry Williams – like many others – couldn’t break through in the country music he loved.

In 1981, he recorded an album in Los Angeles – “I should’ve at least gone to Bakersfield to cut it,” he laughs now – that was set to be released on Mercury Records Nashville before being pulled. Later released as part of his reissue series, this “lost country album,” now titled Don’t Give Up on Me, revealed the Dogg’s facility with the slide-and-glide of contemporary country in that moment and further emphasized his facility with earlier honky-tonk and Nashville Sound traditions. In 2020, after a late-career resurgence fueled by a new generation of fans and friends, he signed with Oh Boy Records (the label started by John Prine, whose “Sam Stone” he covered powerfully in 1972), came to Nashville, and released the acclaimed, country-infused Sorry You Didn’t Make It.

Beyond these milestones, both good and bad, country has remained crucial to Swamp Dogg’s sound. He’s covered country (and country-adjacent) songs. He’s written country-rooted songs, too, many of which (like “I Was Born Blue”) gain resonance from the racial juxtaposition in both sound and theme. And this expert producer and arranger has always noted the country roots of his sound, from the twangy rasp of his singing voice to his choice of instruments. “Everything I write and sing comes out country, and that’s why I have to take so much time in arrangements and instrumentation,” he attested in 2009, “because if not I’d just be cutting a bunch of country records on black people. And we know that black people are not makin’ it in country.”

Fifteen years after those comments, it’s still very hard for Black people to make it in country. The racial barriers remain tenacious and enforced, even in the aftermath of breakthroughs both famous and more significant. In other ways, though, country music might finally be coming around to Swamp Dogg’s way of thinking and being. Not only have the last few years seen a renaissance in Black country from radio-friendly pop to rootsy Americana, but they’ve also produced a growing recognition of Black musicians’ historical and contemporary centrality to the genre. And thanks to writers like Alice Randall and Francesca Royster, both of whom discuss Swamp Dogg in their pivotal works of reclamation, the larger Black country history that Jerry Williams represents has come closer to the foreground. In this context, Blackgrass feels less like a daring intervention and more like a welcome message from an elder who helped forge pathways and now gets to walk them alongside the younger folks following in his example.

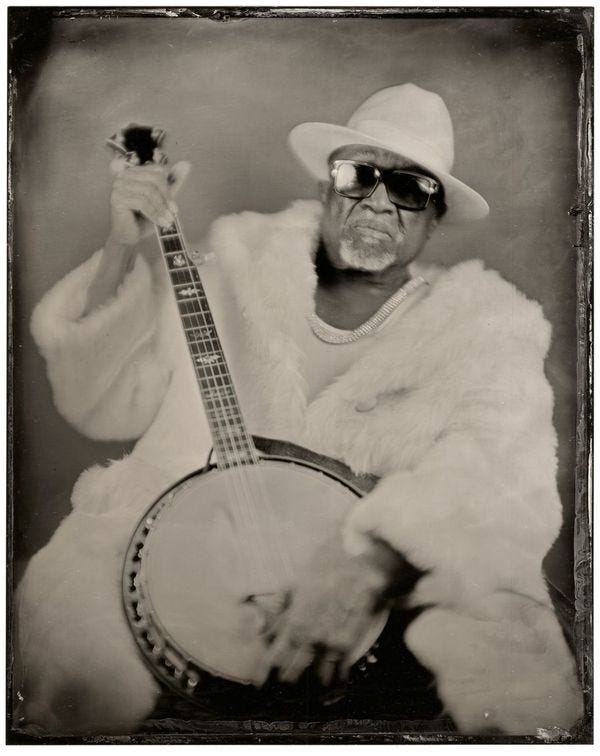

All that is important, but the primary reason why Blackgrass is so valuable is because it’s fucking great. Recorded in Nashville with an all-star group of musicians, the record explodes with the sparkling energy that’s always characterized the best Swamp Dogg recordings. The string-band arrangements are a perfect new addition to his sound (which has included everything from calypso to autotune-assisted drone), and he gives particular pride of place to the African-descended instrument that sits, and thrums, at its stylistic center. For Swamp Dogg, the banjo is both a prerequisite for bluegrass – “You can take Fats Domino and put a banjo on his records – man, you got some bluegrass, you know?” – and a reminder of the Black banjo traditions that (thanks to Our Native Daughters and many others) have been recuperated and amplified in recent years. The banjo, which Swamp himself is pictured holding on the album’s back cover, but which is played here by Noam Pikelny, centers tracks from the opening hoedown “Mess Under the Dress” forward.

He surrounds the banjo with a mix of fiddle, mandolin, and guitars that gives Swamp Dogg the most fully acoustic context of his career. (Notably, he also mostly doesn’t bother with horns this time: “You gotta be careful of how you use the horns in bluegrass. Or blackgrass.”) And what a lineup of musicians have joined him. He brings all three of Marty Stuart’s Fabulous Superlatives – guitarist Kenny Vaughan, multi-instrumentalist Chris Scruggs, and drummer Harry Stinson (who appears here singing high-tenor background vocals) – as well as mandolinist Sierra Hull, dobro master Jerry Douglas, fiddler Billy Contreras, and utility player Rory Hoffman. At times, as on “Your Best Friend,” the band is a fireball, achieving a polyrhythmic analogue to the Dogg’s funky 1970s recordings. At others, like the stately “Curtains on the Window,” it cradles Williams as he dives into ballads of personal heartbreak and societal longing.

Beyond the core musicians, a few of the Dogg’s high-profile friends show up for the Blackgrass party. Margo Price and Jenny Lewis each offer playful duets. Lewis’ take on “Count the Days” (originally a hit for Inez & Charlie Foxx) is particularly effective as she bounces off of Williams in call-and-response while the Cactus Blossoms and Justin Vernon each offer supportive harmonies. The most striking appearance comes from Black Rock Coalition co-founder and Living Colour guitarist Vernon Reid on “Rise Up,” a song that Williams originally wrote (and produced) for the Commodores in 1976. He wrote “Rise Up” to emphasize the band’s ability to “tear the house down” with their instrumentals, which made up the core of the Commodores’ early albums. (He does note, with satisfaction, that “I was one of the people who helped make Lionel Richie believe he could sing,” a poignant detail given Richie’s success as a solo superstar and country-R&B crossover hitmaker.) In keeping with the era’s assertive, celebratory soul, the Commodores’ “Rise Up” rides a bubbling MGs groove that makes the shouted title phrase sound like an invitation to get both party and revolution started.

Here, Swamp Dogg and his Nashville A-team reinvent “Rise Up” as a country rave-up suitable for any barn dance. Sawing fiddle and circling banjo dance between major and minor sections, with the joyous “Rise up!” chorus kicking up dust along the way. And then, about two minutes in, Vernon Reid comes in with a trademark screaming electric solo. “The first couple times I heard it, it scared the shit out of me!,” Williams admits now. “He listened to some Swamp Dogg, and he had heard of Swamp Dogg, but I wanted Vernon Reid. I wanted the Vernon Reid that had hit albums and shit. I didn’t wanna turn him into one of Swamp Dogg’s musicians.” Reid’s solo – “which takes us to another dimension” – nods to the Black Rock tradition (and its funk and jazz corollaries) that reclaimed the sounds of rock ‘n’ roll as a Black-centered, future-minded enterprise in a similar way to the work that Swamp Dogg and his crew were working on as he did “total destruction to your mind” from 1970 forward. It’s kind of surprising that the two had never worked together before, but what a debut for this dream team.

As great as the playing is, the album ultimately – and appropriately – remains a showcase for Swamp Dogg’s voice. At eighty-one, his singing has never sounded better, a sustained and flexible tenor that fits the high-lonesome setting. He wrings all the emotion out of Floyd Tillman’s country classic “Gotta Have My Baby Back” and “Have A Good Time,” originally a 1954 hit for Tony Bennett, which draws both on Bennett’s smoothness and on an additional influence: Williams modeled his delivery of the word “time” after Sarah Vaughan, “one of the greatest singers that I have ever heard.” He offers a distinctive take on his “To the Other Woman” (which he and Gary “U.S. Bonds” Anderson wrote for Sandra Phillips, who recorded a smoldering version in 1970) and sounds both ageless and older-and-wiser on his yearning original “This Is My Dream.” He gives a harrowing spoken performance on “Murder Ballad,” which he co-wrote with a young rapper and which offers a bracing contribution to another section of the country canon. And lest you think the album eschews the raunchy fun that’s always been part of the Swamp Dogg experience, tracks like “Ugly Man’s Wife” find Williams winking at the hokum continuum with suitable trickster aplomb.

His most affecting performance is “Songs to Sing,” which – uncoincidentally, perhaps – is the song most deeply rooted in Swamp Dogg’s life story. The ballad was originally recorded by Charlie Whitehead, “my best friend,” who grew up nearby in Virginia and whose striking voice reminds of Wilson Pickett while possessing a twangy moan all its own. Williams recorded Whitehead a lot in the 1970s, when the Dogg took up residence in Muscle Shoals as both artist and producer. “Songs to Sing” is probably the best of their collaborations, now collected on a fine anthology. A plea for justice and peace over Otis Redding-recalling church chords, it’s delivered by Whitehead with a kind of quiet desperation that befits the song’s dream of a song that could change the world by its performance. “I just wanted to include him some way in this album,” Williams says now. “I wanted Charlie to go with me, that’s all. He was my buddy.” Swamp Dogg’s tender 2024 version aches with loss, most directly of his friend (who he honors in a spoken dedication at the end as the band swells behind him) but more widely of a yet unfulfilled promise of sing a better and more just world into existence.

Speaking of which, Alice Randall writes in My Black Country that Swamp Dogg “creates a rural Black center for the world” with his music and example. With its big sound and even bigger vision, rooted in tradition but unwilling to stick to expectations in either form or content, Blackgrass renders Randall’s insight even more perceptive. The album is equally profound and playful, filled with songs and performances that honor the music and redefine how we might hear it. Which, at his best, is what Jerry Williams has always done. I don’t know where Swamp Dogg will go next – he tells me he has “four more genres” that he wants to try, “but only if I can keep them black.” But I know this: Wherever he goes, whatever songs he chooses to sing, whatever myths and histories he expands and explodes, I’ll be right there with him. I hope you can make it too.

Special thanks to my brilliant friend Kandia Crazy Horse, for many Dogg-related things (and more) over the years.

(Photo by David McMurry)

If you like what you’re reading here, please think of subscribing to No Fences Review! It’s free for now, although we will be adding a paid tier with exclusive content soon. Also, if you’d like to support our work now, you can hit the blue “Pledge” button on the top-right of your screen to pledge your support now, at either monthly, yearly, or founding-member rates. You’ll be billed when we add the paid option. Thanks!

Can't wait for the (possibly un)authorized Swamp Dogg bio.