Stevie Wonder: A Love Letter in 16 Songs

David picks his Wonder-ful favorites in honor of the singer's 75th birthday

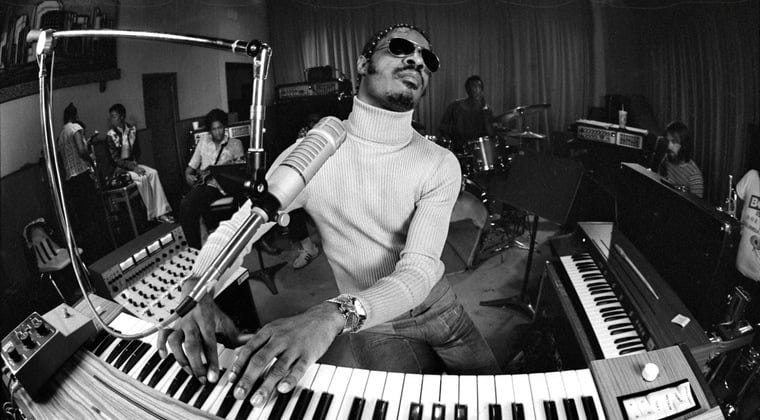

Stevie Wonder is one of the most influential and enduring artists of the rock & soul-era. He became the music world’s major black superstar, and arguably the most significant popular artist period, at just the moment that Sly Stone began to disappear. I’m guessing you don’t need much of an introduction. Born Steveland Morris, in Saginaw, Michigan, and raised in Detroit by his mom (and occasional cowriter) Lula Hardaway. Signed to a recording contract when he was still only 11, Little Stevie Wonder, as he was first billed, grew up hanging out at Motown and absorbing the lessons of studio musicians like drummer Benny Benjamin and keyboardist Earl Van Dyke. One peculiar aspect of Wonder’s catalog is the way his early recordings, even his radio successes, didn’t always closely adhere to the Motown Sound associated with labelmates Martha Reeves, the Supremes, or the Four Tops. His music was always of a piece with Hitsville USA but also, from his career-launching live hit “Fingertips–Part 2” to his interest in politically charged songs to just the sonics of his records, something apart. That distinctiveness was only heightened after he gained artistic control over his career with 1972’s Music of My Mind.

Wonder was a great album artist and a great singles artist, but like most other people my age, I heard him first on Top 40 radio and only came to his albums later. Even then, my first Stevie Wonder albums, picked up as an undergrad, were the hits collections Original Musiquarium 1 and, his entry in Motown’s “Anthology” series, Looking Back. I don’t have any Stevie album hot takes, really. I don’t think Songs in the Key of Life, the consensus critical pick for his masterpiece, is his very best—nothing against Key, understand, it’s just that Talking Book and Innervisions are standing right there. I guess the other bit of common wisdom I’d want to push back on, jut a little, is the one where Talking Book is his first legit great album. As you’ll see, I think his pre-independence Signed, Sealed, Delivered remains wildly underrated.

Charles will drop his deep cut album track considerations here on Friday. Today, with my 16 picks below (Why 16? Why not?), I stick almost entirely to Wonder’s singles, my fave favorites among so many. What did I miss?

1. “Blowin’ in the Wind” (from Up-Tight, 1966)

All popular music is implicitly political, but no one has succeeded with explicitly political music on the radio more often than Stevie Wonder. Throughout the ‘70s and into the early ‘80s, Wonder scored politically charged hits, several of which I’ll be getting to soon enough. Stevie’s first political statement, and Motown’s, came with his 1966 version of Bob Dylan’s famous folk-revival anthem. Clarence Paul, Stevie’s mentor at the label, heard him singing the Dylan song, encouraged him to record it, then lobbied hard for its release against significant resistance from the Motown brass. According to critic and historian Nelson George, label pushback didn’t entirely subside even after the song topped the R&B chart and cracked the Pop Top Ten. Not for the last time, Stevie’s recording takes a standard and entirely reinvents it. While Dylan’s original muses from a philosophical distance about troubles that’ve been entrenched forever and look to remain so, and where Peter, Paul & Mary’s hit version of the song can feel a bit as if it were patting itself on the back for facing what no else sees, Wonder’s version feels like the Civil Rights Movement itself—fueled by the gospel impulse, driven by Paul’s call-and-response backing vocal, and with a rhythm that’s deliberate but energizing and on the march. Freedom is blowing in the wind, Wonder’s buoyant version shouts. Together we can catch it.

2. “A Place in the Sun” (from Down to Earth, 1966)

Wonder followed up his version of the unmistakably political Dylan number with “A Place in the Sun,” which was also political, albeit a little on-the-down-low. Written by Motown house songwriters Ronald Miller and Bryan Wells, and originally intended for labelmate R. Dean Taylor, the song fits comfortably into that long-gone commercial category “Inspirational,” alongside universalist standards like “You’ll Never Walk Alone,” “I Believe,” “Somewhere Over the Rainbow,” or “The Impossible Dream.” In that familiar context “A Place in the Sun” couldn’t possibly have been any less controversial: It became Wonder’s debut entry on the “Easy Listening” chart. On the other hand, close listeners couldn’t miss the record was a sly anthem for civil rights, with lyrical details, such as “like a long, lonely stream I keep running toward a dream,” that clearly called back to Sam Cooke’s “A Change Is Gonna Come.” Fast forward to a different sort of freedom song and the famous destination in Bruce Springsteen’s “Born to Run,” “We're gonna get to that place where we really wanna go and we'll walk in the sun,” was inspired by Wonder’s dream. Stevie would testify more fiercely many times ahead, but the smooth, measured croon he uses here, plaintive yet effervescent, remains undefeated.

3. “I Was Made to Love Her” (from I Was Made to Love Her, 1967)

Speaking of Stevie and fierce testifying… Most Motown acts had developed their (often) melismatic singing styles as kids at church, but such gospel-bred vocalizing was something Wonder picked up primarily only when he was older, mostly by mimicking sounds he heard on the radio. Ahead of the session for “I Was Made to Love Her,” producer Henry Cosby (who co-wrote the song with Stevie, Stevie’s mom, and Sylvia Moy) famously took Wonder to hear a local Detroit minister, urging the young singer to mimic the preacher’s cadence and tone. The 17-year-old Wonder was a quick study—though it would be characteristic of his mature style that what he took for himself was a kind of declarative, preacherly shout and, as for the note-bending associated with most soul singers, not so much. His child’s voice had deepened now, and you can sense his delight in the passion his instrument’s new textures allow him. The sound of the record anticipates where he’s headed in other ways, too: His signature chromatic harmonica sound is here, and the record also marks Wonder’s first studio use of the clavinet. “I Was Made to Love Her” is a rough and funky pop wonder, pun intended, though credit is also due to the indomitable bass line (best heard on the breakdown at the bridge) from Funk Brother James Jamerson.

4. “I Don’t Know Why” (from For Once in My Life, 1968)

In his 1986 biography, Stevie Wonder, John Swenson describes Wonder’s vocal on “I Don’t Know Why” as “obviously inspired by Otis Redding.” I hear that, though I have to say Wonder’s soulful final testifying puts me more readily in mind of Ray Charles. At the same time, I appreciate what Steve Lodder, author of Stevie Wonder: A Musical Guide to the Classic Albums, is getting at when he describes Stevie’s performance here “as almost like a fusing of McCartney and Jagger—unfunky phrasing, but nonetheless impassioned.” If we consider these takes to be complementary rather than competing, maybe what they point to is how Wonder’s music at this still early point in his career was already becoming unclassifiable. The deep, haunted-house clavinet up top; a blues impulse narrative of sticking with a lover who treats him like a fool, kicks him when he’s down, and yet he can’t shake her; the intensity building into a sound that synthesizes the shimmering and the scuffed, rock and pop and soul together, that doesn’t sound all that Motowny but does sound like one person and one person alone. Stevie generis.

5. “Signed, Sealed, Delivered I’m Yours” (from Signed, Sealed & Delivered, 1970)

In pop music, catchiness is job one, a goal that trumps all other values, a quality itself sufficient to greatness. By that measure and all of his other Wonder-fullness aside, Stevie Wonder is a great pop artist. His hooks stick and stay stuck, and his two dozen or so biggest singles are masterpieces of the It’s-Got-a-Good-Beat-and-You-Can-Dance-to-It aesthetic. Wonder’s first solo production credit, “Signed, Sealed, Delivered I’m Yours,” just might be his catchiest of all, which is to say his greatest. It’s a banger. “I done a lot of foolish things that I really didn’t mean,” Stevie pleads guiltily. It’s his melody, though, and the indelible, irresistible bass line from Bob Babbitt (Stevie’s touring bassist, on his debut Motown studio session), that transforms Stevie’s regrets into a perpetual motion machine for fun.

6. “Heaven Help Us All” (from Signed, Sealed & Delivered, 1970)

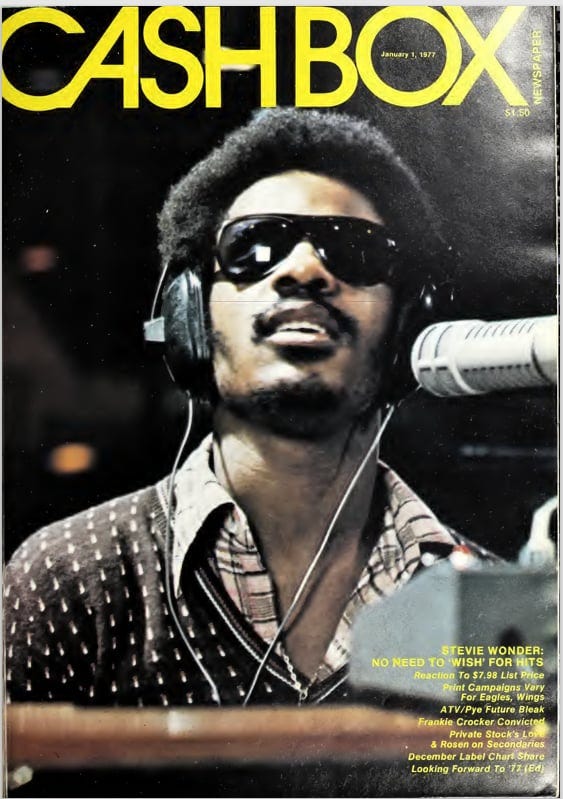

“As close to a gospel record as anything Stevie ever recorded,” per critic Dave Marsh. “[A]nother step into the total performer portrait that he has been cultivating,” per Cashbox. And the greatest socially conscious ballad performance of Wonder’s career, per me. Written by Motown songwriter Ron Miller (who also wrote “For Once in My Life”) the song is righteous and generous at once, politically brave too, both back then and right now. These days, its second verse—"Heaven help the Black man if he struggles one more day / Heaven help the white man if he turns his back away”—would be muzzled via executive order. The mass choir here, a still novel choice the year after “Oh Happy Day,” borrows the specific sounds of the black church to engage in universal call and response.

7. “We Can Work It Out” (from Signed, Sealed and Delivered, 1970)

The music Wonder created after breaking free of the Motown assembly line in the early 1970s, plus his move to writing (nearly) all his own material, were business and artistic triumphs. But we lost something in this evolution, too, as prior to the shift Wonder was a first-rate interpreter of other people’s songs. He regularly made old music new, covering everything from beloved standards to recent hits. At least before moving on he gave us his version of “We Can Work It Out,” which I hereby crown as Greatest Beatles Cover Ever. The Fab Four’s rational, calm reading of “We Can Work It Out,” for example, always sounds one-sided to me, like the guy in the song has all the power and knows it: He can stay up and work it out or he can say goodnight but, either way, he’ll be fine. Wonder’s version sounds committed, vulnerable, desperate. He pushes and pleads, sweet talks and screams, even weeps, and with Pistol Allen’s hard and loose drum work sounding as if he’s making his kit inch across the studio floor, the rocking rhythm amplifies the stakes. As the record fades, Stevie’s still fussing and fighting, still there working, and the sun’s coming up.

8. “Superstition” (from Talking Book, 1972)

Another example of Wonder being unconstrained by genre or, rather, being drawn to claim and remake any sound he digs. He supposedly wrote it for Jeff Beck, but it was such a modern rock track that in the mid-seventies I used to hear it regularly on my Kansas City album-oriented rock outlet, KY102. Playing it over and over again this past week, I have two takeaways. 1) That clavinet line and those punchy horns layer polyrhythms, of course, that make the song so itchy and irresistible but are also whole-new-song-deserving melodies of their own. “Superstition” is polymelodic. 2) In our era of conspiracy theories, alternative facts, and doing your own research, “Superstition” is more relevant than ever.

9. “Blame It on the Sun” (from Talking Book, 1972)

Wonder is widely recognized as a great rock and soul songwriter. What’s overlooked is that Wonder has made numerous modern contributions to that pre-rock-n-soul era tradition of sweeping, romantic pop balladry that fits, broadly speaking, under the title of the Great American Songbook: “Yester-Me, Yester-You, Yesterday,” “I Believe (When I Fall in Love It Will Be Forever),” “I Just Called to Say I Love You” (its holiday-by-holiday conceit sounds like something from Irving Berlin), “Never Dreamed You’d Leave in Summer,” “You Are the Sunshine of My Life,” and a dozen more. Talking Book’s brokenhearted frame to “You Are the Sunshine…,” “Blame It on the Sun” is one of Wonder’s best in this tradition, an anthem to the confusion following falling out of love that was co-written with the woman who would soon to be Wonder’s ex-wife, Syreeta Wright. You can easily imagine the song anchoring the first act of a stage or screen musical, moving plot and reinforcing the hearts and dreams of its characters—broken now, and lost, but still reaching for some bittersweet way to move forward. The closing “Your heart blames it on you this time,” by background singer Lani Groves, is the perfect theatrical tag.

10. “Living for the City” (from Innervisions, 1973)

As great as any song or recording in Stevie’s career—and, you know what, let’s just go ahead and delete the “in Stevie’s career” part of the claim. The 3:39 single edit is perfect, the four-minutes longer Innervisions version is better. The urgency of his country storytelling, the intensity of his big city rhythms, climaxing midway through for the intense eight seconds he holds that “livin’ for the cih-taaaaay.” The extended album version includes a still-hayseed-enough “hard time Mississippi” to “skyscrapers ‘n everything” melodrama that would launch a thousand hip hop skits. When we return to the song, Stevie’s voice is strangled by rage and fear. He worries the title line, “Living for the city—just enough,” until it sounds like a ticking bomb. Don’t push him. He’s close to the edge.

11. “You Haven’t Done Nothin’” (from Fullfingness’ First Finale, 1974)

Wonder’s clavinet line here is so funky, so sticky, and the “doo-doo-wop” hook (with the Jackson 5!) so irresistibly singalong, that I can imagine this one might have been a big hit minus any actual verses. With its lyrics about no-count politicians included, it went to No. 1, R&B and Pop, and has proven frustratingly timely ever since. “We are sick and tired of hearing your song, telling how you are gonna change right from wrong.” Nixon apparently resigned two days after it hit stores. Time to re-release.

12. “I Wish” (from Songs in the Key of Life, 1976)

No shortage of cuts from Songs in the Key of Life I might have chosen. I’m especially fond of “Love’s in Need of Love Today” and “As,” and also want to shout out my wife’s childhood Wonder favorite, “Sir Duke.” But “I Wish” is the one that sticks with me. I wish more people thought of it as the Christmas song it clearly is. Beyond its first verse about cherishing “the joy the day would bring” even when there were no presents under the tree, it was in the Top Ten Christmas week in 1976, on its way to No. 1 two weeks later. I also appreciate the way Stevie indulges some nostalgia for childhood days, not in any politically programmatic or reactionary way, but as a version of the blues impulse, acknowledging the losses that shaped him. It’s notable, too, that what Stevie misses here—poverty, getting in trouble at school, getting whipped at home, working on mysteries without any clues—is not some rose-colored utopia but simply a world where all the myriad limits were at least still familiar. I wish.

13. “I Ain’t Gonna Stand for It” (from Hotter than July, 1980)

Here’s where Stevie Wonder plays with elements of country music past and in the process predicts a future... You don’t grow up in mid-century Michigan without hearing your share of country music, and Wonder had recorded country songs here and there throughout his career. He cut Merle Travis’ “Sixteen Tons” in 1966, put a live version of Willie Nelson’s “Funny How Times Slips Away” on the B-side to his “Hi-Heel Sneakers” single the year before, crooned “By the Time I Get to Phoenix” on his second live album, and even appeared at the Grand Ole Opry in 1979. My second favorite Stevie-does-country moment: Early in a 1984 concert in Detroit, Wonder broke out a hyper jaunty version of Ernest Tubb’s signature hit, “Walking the Floor Over the You.” “You like that?” he asks the crowd when he’s done. “Yeaaaah!” “You wanna hear more more like that? “Noooooo!” Stevie tells them he’s sad about their reaction, but you can’t blame people who’ve paid to see Stevie Wonder if all they want to hear is Stevie Wonder songs.

My favorite Stevie-does-country moment is “I Ain’t Gonna Stand for It.” His hyper twangy impersonation of a country singer—he’s not making fun but is totally having some—in verses that play around with country (and blues) cliches about cheatin’ lovers are as gripping as they are unexpected. He plays with country sounds too: That opening guitar strum hints at a lot of Nashville records but I flashed first to some Kenny Rogers cut or other and Stevie’s tinkling piano fills put me in mind of, say, Ronnie Milsap. On the insistent chorus, though, he shifts to pushing against that sad state of affairs, and kicks up the groove too, laying down one of Wonder’s most impressive and busiest turns behind the kit. Back in the verses, the rhythm and twang, had me flashing on Blanco “The Git Up” Brown, who I hope cuts a modern country version of this one ASAP.

14. “Front Line” (from Stevie Wonder’s Original Musiquarium 1, 1982)

It’s unclear to me exactly when Stevie wrote this anti-Vietnam, pro-disabled veteran rager, but it was only released as one of a handful of unreleased cuts included on the indispensable collection Original Musiquarium. It’s worth noting that was in 1982, a full two years before Bruce Springsteen released his similarly themed “Born in the U.S.A.” Its R&B-with-rock-guitar arrangement, meanwhile (thanks to a blistering lick by Benjamin Bridges), was ahead of Michael Jackson’s “Beat It” and Prince’s guitar-centric pop breakouts, as well. How is it that “Front Line,” one of Wonder’s catchiest hooks, angriest singles, and pithiest lyrics (“They had me standing on the front line / But I stand at the back of the line when it comes to gettin’ ahead”) didn’t even crack the Hot 100? Play this record loud.

15. “Part-Time Lover” (from In Square Circle, 1985)

“Part-Time Lover,” with backing vocals by Luther Vandross, was a monster hit in 1985, topping the pop charts for a week and the R&B charts for six, and it goes down among Wonder’s most credible accounts of what’s bad for the goose also being bad for the gander. But the reason I had to include it here is that groove. As on “Signed, Sealed, Delivered I’m Yours” above (and also “I Just Called to Say I Love You,” a pop and R&B chart topper from the year before), Wonder’s synth bass line on “Part-Time Lover” rolls comfortably, gently, yet overwhelmingly forward—it has what tennis watchers call easy power. No wonder Boogie Down Productions (“Part-Time Suckers”), Tupac Shakur (“Part-Time Mutha”), and 50 Cent (“So Amazing”) each built jams of their own around Steve’s smooth groove.

16. “Positivity” (from A Time to Love, 2005)

Twenty years ago, Wonder released this upbeat gem, determined to summarize his work and his approach to life. Its bouncy piano reaches back to early J5 hits but also sounds like it’s spent time listening to “MMMBop” loud and on repeat. Maybe even some “O.P.P.” too: Stevie’s not rapping here, but his internal rhymes and motor mouth flow let you know he’s checked out plenty of hip hop. He sings that people always ask him, “What do you see tomorrow in the human plan?” If we’ve been paying attention, we should be able to predict his answer. Life can be rough but it’s better than the alternative; be positive but don’t fool yourself; we can find unity but only if we have a vision large enough to imagine it. He’s for “positivity, because that's the energy the world needs.” Thanks, Stevie, for the reminders.

(Want more Love Letters? I’ve penned them to Elvis Costello, Maria McKee, and Sammi Smith while Charles has written mash notes to Nanci Griffith, Ronnie Lane, Nick Lowe, The Roots, Sly & the Family Stone, Swamp Dogg, and Wilco.)

If you like what you’re reading here, please think of subscribing to No Fences Review! It’s free for now, although we will be adding a paid tier with exclusive content soon. Also, if you’d like to support our work now, you can hit the blue “Pledge” button on the top-right of your screen to pledge your support now, at either monthly, yearly, or founding-member rates. You’ll be billed when we add the paid option. Thanks!

I missed "I Ain't Gonna Stand for It" Tuesday when I played (and even danced to!) some of my Stevie favorites. Thanks David.

Speaking as a pretty near life-long Stevie acolyte--I'll plug my book Higher Ground about Stevie, Aretha and Curtis Mayfield--I couldn't have come up with a better 16, though I'd always make room for "As".