Start Creating Feeling

Charles Hughes on Stop Making Sense

The reissued Stop Making Sense is part of a busy season for concert films. Taylor Swift’s massive Eras Tour dominated the box office in October, Beyonce’s Renaissance seems sure to do the same in December, The Last Waltz is back in theaters for its 45th anniversary, and the Talking Heads’ 1984 documentary has also achieved a modest but still successful run in theaters. These documentaries have clearly tapped into a zeitgeist beyond artist prominence, weighty anniversaries, or – in the case of Stop Making Sense – the imprimatur of hip studio A24. Perhaps it’s about the post-pandemic trend towards event moviegoing, and it’s also probably about the way that live concerts grow increasingly unaffordable and inaccessible. The success of the reissued, spiffed-up Stop Making Sense also speaks to the enduring influence of the long-dormant band and their recent move (especially David Byrne’s) into the role of the beloved cultural elders from which they once represented a generational break.

The renewed love also reflects the fact that the movie is fucking great. A lean 88 minutes, Stop Making Sense captures the show’s feverish energy and unique staging, and presents it through a distinctive cinematic aesthetic. Director Jonathan Demme, the band, and their respective crews use techniques from sources as wide-ranging as Japanese Noh theater, German Expressionist film, and the sweaty energy of R&B performances to create something that is both a representation of the band’s acclaimed 1983 tour and something else entirely. A boisterous blend of motion and music, Stop Making Sense has earned its celebrated position among concert movies, even as nearly two generations of filmgoers haven’t had a chance to see it as it was originally intended.

I’m one of them. After years of watching it on a cruddy VHS, then a nicer DVD, both on a regular-ass TV without any notable sound system, the restored big-screen version is exactly the revelation that I hoped it would be. The picture is bright and vivid, managing to gleam while still maintaining the original’s seam-showing honesty. And the new mix is truly remarkable, pulling elements up and out to fully reveal the interplay of the ensemble as it grows from the stripped-down songs at the beginning to the compounding catharses of its final section. I know these songs and these images very well after thirty years of Talking Heads fandom, but this still feels like a gloriously new experience.

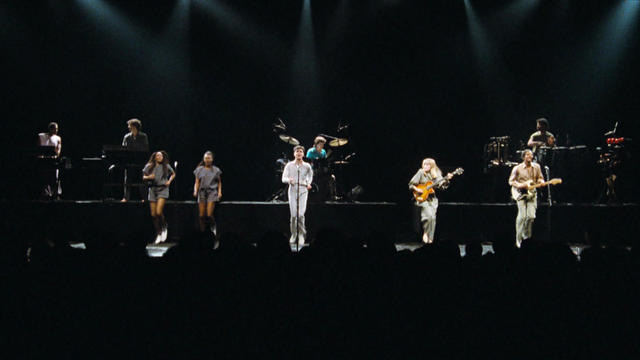

The movie (and the live show it documents) moves along a clear narrative path, with a first act that shows the band and set being built piece-by-piece on a bare stage. David Byrne enters first, with acoustic guitar and boombox, for their early “Psycho Killer,” which climaxes with Byrne balletically stumbling around the stage as stagehands work behind. Then bassist Tina Weymouth arrives and they skip ahead in the band’s chronology to “Heaven,” a beautiful invocation of a place where the party doesn’t stop, they only play your favorite songs, and – crucially – “nothing ever happens.” In the context of what follows, “Heaven” sounds like an invitation to the audience, welcoming them (us) into what begins when drummer Chris Frantz comes on next and the group’s original trio gallops through “Thank You For Sending Me An Angel” like an art-school Tennessee Three. Then guitarist/keyboardist Jerry Harrison – who joined for their first album – comes aboard, and then they’re joined by the tour’s astonishing roster of additional musicians: vocalists Ednah Holt and Lynn Mabry, percussionist Steve Scales, guitarist Alex Weir, and keyboardist Bernie Worrell. This crew – who collectively represent a legacy encompassing P-Funk, The Family Stone, Chic, and the Brothers Johnson, among others – doubles the band’s size, reflects the increasingly layered arrangements of their records, and makes the rest of Stop Making Sense into a near-continuous flow of sound.

As great as all the players are individually, and as central as their musical conversations are collectively, it’s hard not to single out Tina Weymouth. With her bass clear and crisp in the new mix, Weymouth is both anchor and engine to the group’s rolling polyrhythms as they emerge and complexify. Stepping to the backline to play synth bass only emphasizes this, as she grooves alongside Frantz, Scales, and Worrell. When she steps forward to sing Tom Tom Club’s enduring “Genius Of Love,” she reveals herself a compelling frontwoman whose playful poise serves as both counterpoint and complement to Byrne’s wiry pantomime. (The fact that she often doubles his dances while carrying and commanding a bass is truly a backwards-in-high-heels situation – same goes for the point where Holt and Mabry pause their windshield-wiper motion across the microphone and each other to nail their stabbing, soaring backgrounds.) One of the pleasures of multiple viewings of Stop Making Sense, in any format, is to focus on a different musician each time – from Worrell’s funk oracle to Harrison’s genial pro – but my eyes and ears kept being drawn back to Weymouth.

It’s worth noting, of course, that the core band is all white and the additional musicians are all Black. This matters in terms of staging dynamics – although the group’s circling choreography and rotating positions mostly avoid the too-common setup of white-people-in-center-and-Black-people-on-margins – and it’s additionally relevant given that Talking Heads’ incorporation of Black sounds from across the diaspora literally and figuratively propelled their emergence into the band presented here. The funk infusions, Afro-pop textures, dance rhythms, and gospel voicings that make Fear of Music, Remain In Light, and Speaking In Tongues such rich experiences all get their due here in ways that – for me, at least – don’t cross the line into feeling particularly appropriative. Even the riskiest moment avoids this problem. Their cover of “Take Me To The River” embraces its gospel roots and engages the crowd in call and response while avoiding the racial mimicry that too often accompanies (even unintentionally) white-led live versions of Black-originated material. (On the other hand, Chris Frantz would do well to turn down the white-boy-MC routine in “Genius of Love” by a few notches.) The shots of a multiracial crowd help too, seeming less like the camera searching for diversity and more like a fair representation of the audience at Los Angeles’ Shrine Auditorium. What’s most helpful, though, is the film’s spirit of mutual musical adventure, a continuous joyous vibe that exemplifies the central and intended irony in the key lyric of “Life During Wartime,” performed here as the furious capper to the first half. This sure is a party. It sure feels like a disco.

And what a party/disco it is. Watching and hearing it on the big screen, I relished anew the moments and images that are deservedly legendary: the wave pattern of Byrne, Harrison, and Weymouth as they dance through the end of “Found a Job”; the lit-from-below nightmare ecstasy of “What A Day That Was”; the lamp dance in “This Must Be The Place”; the aerobic fire of “Burning Down The House” and “Life During Wartime.” These greatest hits offered specific moments of collective joy among the audience: the appearance of Byrne’s famous big suit at the beginning of “Girlfriend Is Better” got a legit cheer from the audience. But I also found myself struck by some less obviously iconic moments: the way Byrne’s stomping foot punctuates his triumphant “oh-OH”s in “Thank You For Sending Me An Angel”; the low angle that makes it look like Holt and Mabry’s voices are powering the (flash)light on Worrell’s face during “What a Day That Was”; Byrne’s goofy donning of a red baseball cap that someone had thrown on stage, adding an unexpected comic juxtaposition with his oversized pants; a sweaty Harrison waving goodbye and giving a small smile of satisfaction at the very end.

The first time I went, it was in a quiet and mostly empty cinema in the early afternoon. I didn’t mind this, since it allowed the sound and images to wash over me. But I’m really glad that my second viewing was the celebration that others have reported. This screening was nearly sold out, with a crowd that included more young folks than I was expecting – I ran into some former students, who told me their parents had introduced them as children to Talking Heads and they’d loved the band ever since. (One was there with her mother, in fact.) Beyond the applause and singing along, I noticed a few people dancing on either side of the theatre starting around the time of “Burning Down The House,” appropriate given both the song’s popularity and its role as the beginning of the film’s full-ensemble second act. There were lots of folks dancing in our seats, too, and even one or two who momentarily stood up and bopped a bit before considerately sitting back down or moving to the sidelines to continue. Around the start of “This Must Be The Place,” the stalwart dancers were joined by others to form small pockets of celebrants on either side of the theatre that grew through the escalating joys of “Once In A Lifetime,” “Genius of Love,” “Girlfriend Is Better,” and “Take Me To The River.” Finally, during the closing “Crosseyed and Painless,” a row of revelers danced in front of the screen, moving from left to right in something between a parade line and Rocky Horror-style audience participation. And then they danced back again. And then across again. And then back one more time before the last echo of the song’s pulsing chorus of “Still waiting” faded away and the credits rolled. I’d like to think they’re still dancing somewhere, maybe in “Heaven” where the party never ends. That must be the place.

The next day, I ran into someone who’s seen Stop Making Sense four different times in this theatrical run. He said that, each time, he’s felt better the next day. I know what he means. Same as it ever was.

(Thanks to Kenneth Burns)

If you like what you’re reading here, please think of subscribing to No Fences Review! It’s free for now, although we will be adding a paid tier with exclusive content soon. Also, if you’d like to support our work now, you can hit the blue “Pledge” button on the top-right of your screen to pledge your support now, at either monthly, yearly, or founding-member rates. You’ll be billed when we add the paid option. Thanks!