The story of Stax Records has settled into the realm of legend. In the 1960s and 1970s, Stax’s artists not only helped define the sound of R&B and soul music, but more generally transformed popular music around the world. The company’s history – from neighborhood label in South Memphis to national symbol of integration to international symbol of Black accomplishment – has become a well-known (if sometimes simplified) shorthand for the Civil Rights era and the promise of music as a mechanism for cultural progress. And its legacy continues, not only through the work of the Soulsville Foundation and Stax Museum of American Soul Music, but through new generations of musicians across genre who celebrate Stax music and collaborate with its creators. It’s an epic story, one as rich and beautiful and challenging as the city it emerged from.

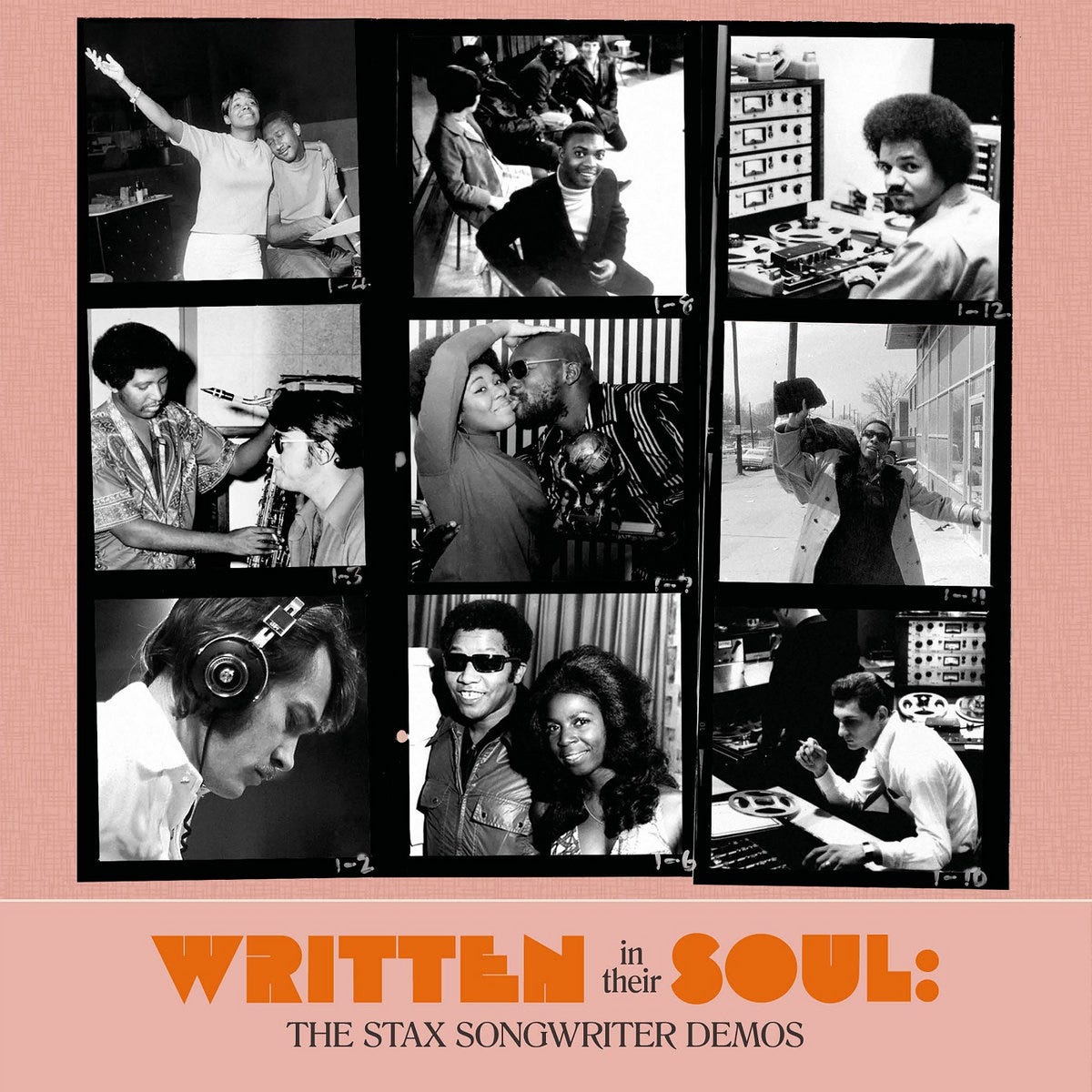

A remarkable new collection adds multiple new chapters, if not entire volumes, to that story. Written in their Soul: The Stax Songwriter Demos is a revelation, a seven-disc alternate history of the label that manages to simultaneously demystify its celebrated output and make it seem all the more remarkable. Spotlighting demo recordings made by songwriters to model their compositions, Written In Their Soul documents the process through which musicians at Stax – famous names and forgotten figures – built their esteemed reputations one song and one session at a time. On this box, Stax’s work is both a noun and a verb.

The box captures the company’s musical roots – from gospel and blues to pop and country – and how the Stax sound developed into new realms of sonic experimentation and funky truth-telling as the years went on. Many of the cuts capture what sounds like the off-the-cuff joy of something special coming together, including occasional rough edges like a flubbed lyric or out-of-tune guitar. As with any good collection of demo recordings (and this is one of the very best I’ve heard), part of the joy is in hearing Stax classics like “Respect Yourself” or “I’ll Be the Other Woman” being born.

But there’s just as much joy – if not more – in the less-familiar and never-before-released songs that make up the majority of the collection. And, in these supposedly rough drafts, there’s often a remarkable precision and polish. Songs like Bettye Crutcher’s “Sugar Daddy” or Mack Rice’s “Come on Down” sound radio-ready even in their supposedly rough-draft form. Regardless, hearing them like this forces the listener to move past expectations and (re)discover the pleasures hiding within. (A small but notable highlight is the fact that – given that many were written with particular artists in mind – the songs are sometimes sung by their writers using same-sex pronouns.) Songwriters sing their own songs and each other’s, while other singers stop by to show how Stax’s many gifted interpreters might deliver them. At its core, Written In Their Soul documents an ongoing, vibrant musical conversation between a community of colleagues.

The box is the product of years of work from producer Cheryl Pawelski and her team at Omnivore Recordings, who collaborated with Stax’s Deanie Parker (co-producer on the final product) and others from the Stax organization to assemble the tracks and learn their origins. (You can read more about the development of the project in this fine article by Burkhard Bilger in the New Yorker.) Lovingly presented and beautifully annotated with notes from Parker and Memphis-music historian Robert Gordon (also a co-producer), Written In Their Soul carries appropriate heft for a project of such artistic magnitude.

Deanie Parker’s involvement here is a welcome reminder of her centrality to the label’s history. From her executive work as its publicist to her stewardship of its legacy following its closure through the Soulsville Foundation, Parker is as responsible as anyone for Stax’s initial success and continuing importance. It is often literally her words in the promotional materials that helped sell listeners and shape knowledge about Stax, and her thoughts in these liner notes sparkle with the same piercing insight that she’s demonstrated throughout her career. But it is as a songwriter and performer – which first brought her to the label – that Written in Their Soul perhaps does her the greatest service. Parker’s known for compositions like “Ain’t That a Lot of Love” (co-written with Homer Banks) and she cut a few records at Stax herself. (Her “My Imaginary Guy” is one of their best nods toward the girl-group sounds of the early 1960s.) Written in their Soul makes an excellent case that she could have sustained a successful career as both singer and songwriter. She soars on the ballad “I’ve Got No Time to Lose,” recorded by Carla Thomas, while “Spin It” swings around the dance floor in a way that allows Parker to both flirt with and command her listeners. She forges particular connection with Mack Rice, with whom she recorded as March Wind. Here, on the bopping “Do the Sweetback,” pulsing “Nobody Wants to Get Old”, and strutting “Until I Lost You,” Parker and Rice sound ready to join Otis and Carla (or, up north, Marvin and Tammi) at center stage.

Other Stax women are at crucial here, just as they were crucial to the label more broadly. Carla Thomas, who scored the label’s first hit with her elegant, self-penned “Gee Whiz,” has several songs featured, most powerfully perhaps the late-night blues of “Another Night without My Man.” Shirley Brown, Veda Brown, Wendy Rene, Mavis Staples, and others appear, but maybe the most significant star turn (other than Ms. Parker’s) comes from Bettye Crutcher.

Working solo and with co-writers in the team We Three, Bettye Crutcher became one of the label’s most successful songwriters in its second boom period. Written in their Soul offers a stunning demonstration of her range as both performer and composer. From the roiling blues of “Third Child” to the morning-after anthem “What You Did to Me Last Night” to the tender “Just the Way You Loved Me” and beyond, Crutcher captures the sweep of Stax’s catalog as well as any individual figure on this set or elsewhere. And she performs maybe my two favorite tracks on the whole thing. “The Yard Man,” written by Crutcher with Mack Rice and Arris Wheaton, is - in that great blueswomen’s tradition - a working-class anthem wrapped inside a sex joke. And she takes “Too Much Sugar for a Dime,” written by Homer Banks and Raymond Jackson (Crutcher’s We Three colleagues), and flips it into a snapping womanist rejoinder. Banks’ pleading version is here and it’s good, although not as good as “Heaven Knows” or “Grandpa’s Will.” But it’s in Crutcher’s hands and voice where the song takes flight.

“Too Much Sugar for a Dime” confronts the unfair politics of sex, love, and work, and it’s not the only song that has such a clear point to make. Even as Stax reached across audiences and aimed for widespread acceptance, the label also – especially in the second phase, led by Al Bell – didn’t shy away from political messages. The work of the Staple Singers is perhaps most famous in this regard, and the set features a run of demos from the group’s first album that is most notable for how deeply writer William Bell digs into the gospel moan of “Slow Train.” But the label extended its political vision in multiple directions. The Vietnam War is a presence here in prayers for peace like Willie Singleton’s “Love Treaty” and the enlisted-man frustration of Mack Rice’s “Three Meals a Day.” The power of community is there in calls ranging from Bettye Crutcher’s “Everybody Is Talking Love” (with its puncturing wah-wah guitar) to John KaSandra’s aching and still-relevant reminder that “We Don’t Need Stone Walls.” And there’s a bunch of discussions of work that doesn’t pay off, or at least doesn’t get the respect or compensation it deserves. This isn’t always gendered (see Mack Rice’s “It Don’t Pay to Get up in The Morning,” or William Bell’s “Can’t Make Enough”), but the mistreatment of (Black) women at the hands of partners and systems gives extra sting to songs like “Too Much Sugar for a Dime.” And, for that matter, it adds a smirking subversion to songs like “The Yard Man.”

There’s a lot I haven’t talked about. I haven’t mentioned Eddie Floyd, or the way his voice emerges from echoing arrangements on the Beatles-esque “Love Is You” or the original version of Wilson Pickett’s hit “634-5789.” I haven’t really talked about Mack Rice, especially the way that he employs clanging guitar in a way that calls out to contemporaries like Bill Withers. (And many of whose tracks – like the original “Respect Yourself” or “Nobody but You” – rock like hell.) I didn’t mention the duet between Eddie Floyd and Mack Rice on “Dammit,” where the two sing in close harmony and hit the title word with equal humor and power. I haven’t talked about the proto-disco tracks that show the label’s facility with what was coming next on the historical continuum of Black pop, or the way that the set both spotlights the work of Booker T. and the MGs and also reminds us of the many other musicians who produced the Stax sound. And on and on, ‘til the break of dawn.

So many other songs, and so many other stories, on Written In Their Soul. But you don’t need to hear about all of them from me. Go get it, put it on, learn some things, and find your own new roads through Soulsville. I promise that you won’t be disappointed. - CH

If you like what you’re reading here, please think of subscribing to No Fences Review! It’s free for now, although we will be adding a paid tier with exclusive content soon. Also, if you’d like to support our work now, you can hit the blue “Pledge” button on the top-right of your screen to pledge your support now, at either monthly, yearly, or founding-member rates. You’ll be billed when we add the paid option. Thanks!