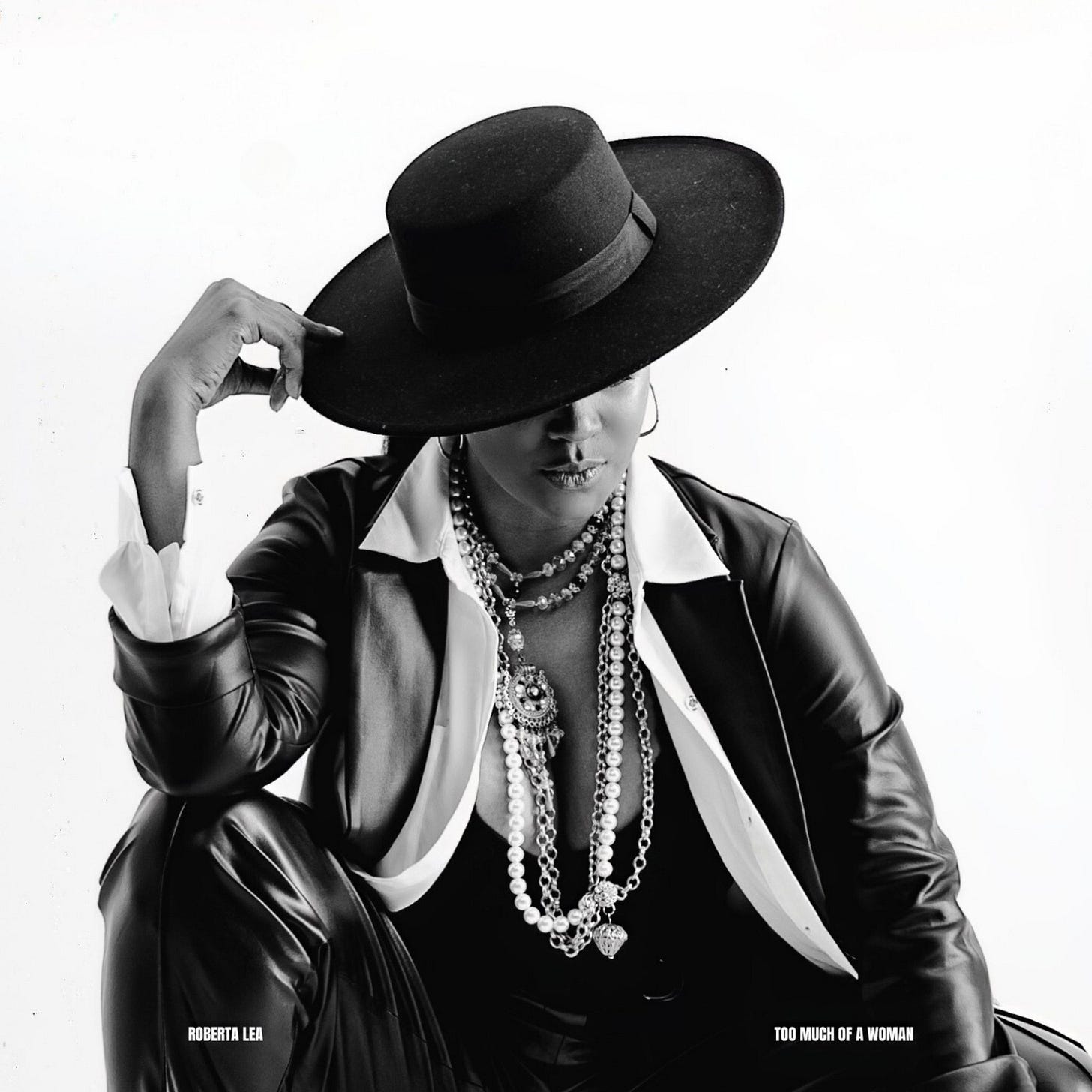

Roberta Lea’s Too Much of a Woman, out today, is one of the best albums of the year. Her debut full-length makes an emphatic artistic statement: she stakes her claim to the wide-open spaces of country music and places herself within multiple intersecting musical traditions. It’s also a stunning piece of music, filled with memorable songs and linked by a loose but clear concept in which Lea tells the story of a woman who learns to embrace and celebrate her wholeness in spite of those (including herself) who would try to convince her otherwise.

This is her first album, but the Virginia-based Lea has been making great records for a while now. David and I are both big fans of her remarkable 2021 EP Just a Taste. (Her single “Ghetto Country Streets” is a particular favorite, a warm reminiscence driven by her deft guitar work.) Lea is part of the larger crew of artists connected to the Black Opry, the wondrous emergence of which has both expanded country’s borders (sonic and otherwise) and claimed necessary space within them for musicians who make an outsized share of country’s best music right now. Too Much of a Woman, a product of a Kickstarter campaign and the outgrowth of years of development and performance, is both culmination and kick-off for an artist who’ll be part of the conversation for a long time.

The album’s title – and title song, whose knockout-punch rhythm matches the boxing iconography Lea used for its video – offers a thesis statement for the larger project. Lea explores how women learn to survive and thrive within the mistreatments and misrepresentations forced upon them by an unfair world, by past traumas, by no-good men, and – importantly – by the internalization of negativity. A former teacher, she brings an educator’s awareness of narrative and structure. Each song opens with a short declarative statement about the main character – “She is fed up,” “She is healing” – a scene-setting device (reminiscent of Lemonade, among many other things) that builds her argument through the songs’ various takes on love, struggle, and joy. Fittingly, it comes through strongest at the end, in the heart-swelling ballad “So Much More,” when the spoken introduction gets longer and lays out the complicated beauty of the supposedly too-much woman to whom Lea has introduced us. “I am she,” Lea assures, “and she is me.” In the song, Lea’s “so much more” shifts from being about the character herself to also defining the partner who loves and supports her because, not in spite, of her rich complexity. What some would call “too much,” in this case, turns out to be just enough.

Lea’s protagonist finds several such spaces of sanctuary on Too Much of a Woman. On the twilight-time ballad “Dinner, Sunset, and Nina Simone,” Lea pays tribute to the North Carolina-born artist as part of a peace-bringing evening ritual that she shares with her partner. She finds refuge on the joyous “Girl Trip,” where she finds comfort (and rowdy fun) with a group of friends. On “Stronger This Time,” she notes how therapy, faith, self-care, and those same circles of friendship help her find clarity in a way that alcohol can’t match. (Not that she’s giving up the good times, shouting out Black-owned companies Uncle Nearest Whiskey and Black Girl Magic Wine as favorites.) She finds peace within – on “Threw It All,” she recounts a woman learning to live with past trauma, welcoming what Dolly Parton (who shares Lea’s gifts for guitar-based storytelling and shining pop arrangements) calls the “light of a clear blue morning” as the swelling arrangement blooms around her.

And, on “Small Town Boy,” she finds community in “the hearts of my global neighbors.” As David wrote here a while back, this celebratory kiss-off and its unstoppable chorus gained extra unintentional relevance thanks to our recent unpleasantness. But, outside of this topicality, Lea’s ode to the worldwide version of the “big backyard” that Molly Tuttle recently sang about is not only a compelling testament to freedom (placing Lea in a longer artistic tradition of Black artists – especially women – who celebrate such mobility as a crucial part of their identity) but also a compelling and joy-filled counterpoint to all of those white-dude country songs that seek to limit country identity (especially for their “girls”) to a mythical small town and the supposedly small minds who inhabit it. Lea will have none of this, boy, charting her journey (some of which is autobiographical) from Dublin to Yokosuka to Lagos and beyond. But, even as she celebrates where she’s been, she also remains rooted in where she is.

Virginia is everywhere on this album. It’s there in the album-opening invocation of “Something in the Tide,” where strings wash in like waves and Lea calls up the region’s unique talents. “In a land that is for lovers, there is room for every kind,” Lea insists. “Every voice, every heart, every soul, and every mind.” It’s there in the saxophone that drives “Stronger This Time,” recalling the Norfolk-centered “beach music” scene of Gary “U.S.” Bonds or Jimmy Soul. (The instrumental, sax-driven outro would sound right at home in the hands of Bonds fan and student Bruce Springsteen.) It’s there on the snapping “Girl Trip,” where Lea and producer Calvin Merazh honor the legacy of Virginia hip-hop innovators like Missy Elliott, the Neptunes, or Timbaland, whose work with Bubba Sparxxx showed that he understood the same kind of banjo/drum-machine juxtapositions that Lea serves up here. And it’s there in Lea’s engagement with country music traditions, from string bands to twenty-first-century pop, as the artist draws together a range of country sounds that give the lie to easy stylistic distinctions even as Lea shows her expertise with each of them.

Indeed, this album is one of the most compelling examples yet of the way that the Black Opry moment both reclaims and reimagines. Too Much of a Woman shows not only how foolish it is for the country mainstream to deny the presence and potential of Black artists – and it’s so damned foolish; there are 5 or 6 songs on here that could and should be massive hits – but also how important it is to create communities who needn’t rely on traditional gatekeepers to celebrate themselves and each other. For many artists and fans, the Black Opry has been its own space of creation and sanctuary, related to the ones that Lea details here. And it’s been a historical project, as well, reaffirming how Black women, in particular, have always been crucial to country music whether or not they’ve been recognized as such.

Lea’s reinvention of “Papa Was a Rolling Stone” deserves particular attention in this regard. The one cover on the album, Lea offers the Temptations classic as a swaying country lament with loping drums, piercing banjo, and insistent background vocals. It’s not just a clever stylistic mash-up, though, or even a welcome gender shift that turns the song into the passing of wisdom between mother and daughter. Lea and the band find a different kind of yearning and anger in the song’s damning details, inside a subtly rocking arrangement that builds to a stadium-ready guitar solo in the bridge. (It’s not the only time that Lea rocks out – both “Make Up Your Mind” and the Jackie Venson-assisted title song build to blazing choruses and soloes.) Though not written by Lea, “Papa Was a Rolling Stone” is a perfect addition to the album and a powerful example of sonic script-flipping.

In a sense, Lea here most directly recalls artistic foremother Linda Martell’s similar remix of the Winstons’ R&B hit “Color Him Father,” which Martell released in 1970 as part of her remarkable (and still under-appreciated) album Color Me Country. A loving depiction of a far more supportive figure, “Color Him Father” in Martell’s version reveals the threads between musical styles, the specific affinity of country and R&B, and the historical ability of Black women artists to transgress genre categories even as their careers too often remain circumscribed by them. Lea’s “Papa Was a Rolling Stone” does similar work, succeeding both on its own terms and as a response to these legacies.

Let me be clear. I’m not just recommending this album so highly because it’s important or really smart, even though it’s both of those things. I’m recommending it so highly because it’s deeply pleasurable. Too Much of a Woman is filled with singalong (or shout-along) melodies, vibrant productions, and arrangements that blend textures and draw attention to Lea’s remarkable singing. The warmth and dynamism of Lea’s voice centers and propels each track, from the rave-ups to the cool-downs, from the piano-inflected new morning of “Threw It All” to “Midnight Matinee,” a restless call-out where Lea is filtered through an effect that makes her soft rumble additionally mysterious and assured. When Lea is plumbing the depths of heartbreak, haters, or self-doubt, she sings with an empathy and perseverance that neither ignores the pain nor is overwhelmed by it. And when the sun shines through – on “Girl Trip,” “Stronger This Time,” “Threw It All,” or the closing love songs – it feels like victory.

Too Much of a Woman is a star turn, a declaration of independence, and a convincing argument that Roberta Lea deserves her place among the most exciting artists in country or anywhere. I love this album, and I hope you will too. Check it out, and turn it up. - CH

If you like what you’re reading here, please think of subscribing to No Fences Review! It’s free for now, although we will be adding a paid tier with exclusive content soon. Also, if you’d like to support our work now, you can hit the blue “Pledge” button on the top-right of your screen to pledge your support now, at either monthly, yearly, or founding-member rates. You’ll be billed when we add the paid option. Thanks!

"I will gladly take the rest of the world

You can have your small town, boy"

What a line.

A fantastic celebration of a revelatory artist. Thanks for shining a light on this amazing musician!