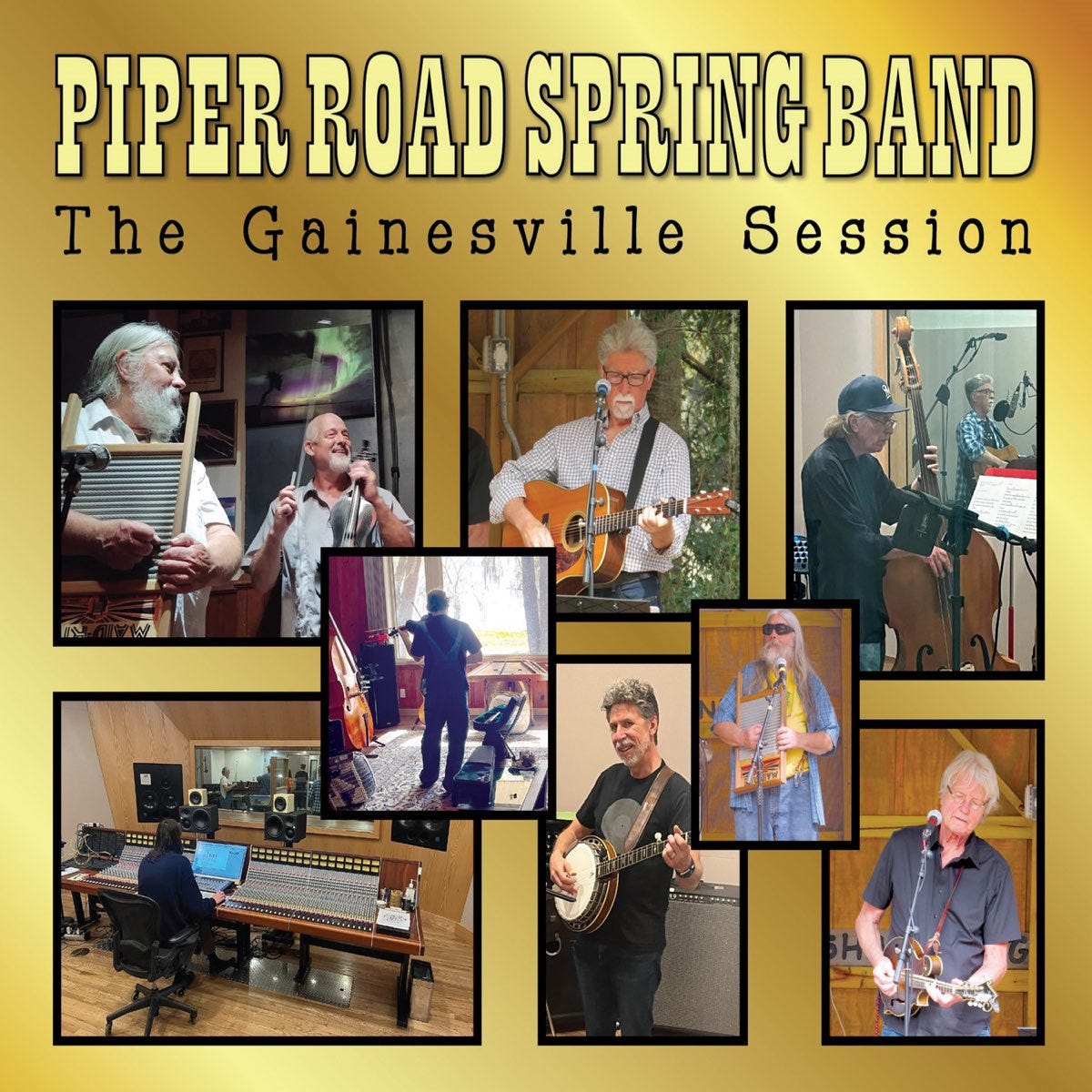

Piper Road Spring Band - The Gainesville Session

Charles Hughes on a new album with a close connection to his heart

It’s not an overstatement to say that I’ve been listening to the Piper Road Spring Band, a Wisconsin-based bluegrass group currently celebrating its fiftieth anniversary, for my whole life. Now, sometimes this kind of relationship emerges due to cultural ubiquity or some sort of inexplicable connection, but in this case there’s a simple reason for this. Bob Mason, the group’s co-founder, mandolin player, one of its primary singers and songwriters for the entirety of its long run, is my uncle. So, from a time before I can remember, I not only heard their recordings, but engaged with them as live performers and real-life people in a way that has remained sustained and sustaining as I’ve traveled as listener, musician, and person.

Even outside of my personal connection, their story draws some familiar arcs. Originally an electric rock band, the group explored acoustic music after being inspired by the Grateful Dead’s acoustic turn and other overlaps between the psychedelic ‘60s and the country, bluegrass, and folk traditions increasingly emergent in the aftermath. After a power outage at one of their regular venues forced them to unplug for the evening, they realized that their bluegrass form was both more rewarding and more popular. Throughout the 1970s and into the 1980s, they played consistently in Wisconsin (sometimes multiple times a week) as well as on the national circuit that helped bridge the transition between bluegrass’ founders and the counterculture-influenced next generation of which they were a part. They played the Opry and shared stages with Dolly Parton, Roy Orbison, and most of the key players of bluegrass’ first and second eras. They also released a few albums, including 1977’s sparkling Kettle Moraine, which became as close to a hit as they ever had. At least so far.

These albums spotlighted their facility with the musical roots (whether they were covering primary sources or writing originals that recalled and remixed. And they made increasing room for the jammed-out, jazzed-up experiments that grew prominent in the “newgrass” age and beyond. At their best, the Piper Road Spring Band’s albums retain a fresh and memorable sharpness, with their expert interlaced playing always at the center. Their line-up changed, they weathered changes in music preference and drinking ages, but – by the early 1980s – they remained a full-time concern with a loyal fanbase in the northern Midwest and points beyond.

This is where I come in. I’m not sure when I first became aware of the Piper Road Spring Band, but it was early enough that they’ve always been a part of my conscious memory. I’ve seen them live countless times, including at my high-school graduation party, and traced changes in their sound and personnel along with them. I’ve listened to their albums a lot and followed the rabbit holes of their influences to discover artists both understandable and unexpected. (I’m pretty sure that the first time I heard a Little Walter song, for example, was in the sly version of “Dead Presidents” they released in the early-‘80s.) And I learned from them as a musician, as well. I started playing violin from a very young age thanks to my admiration of their fiddler, “Big” Al Byla, whose Cajun-influenced playing won championships and whose kind generosity made an equally significant impression on me.

My uncle’s example led me to later pick up the mandolin, and I can hear his influence – and the band’s more generally – in my guitar playing, songwriting, and approach to live performance. (For one thing, my band has played their arrangement of Mickey Newbury’s “Why You Been Gone So Long?” at every show we’ve played. Except the time we played a gospel church service – actually, we maybe should’ve done it there too.) Getting older, and getting to play with them informally a bit, has offered that rare opportunity to play songs I grew up on with the people who recorded them. One of those songs, appropriately, is “Me and My Uncle,” a Grateful Dead standard that was a staple of their shows for a while. They’ve meant a lot to me in many ways.

So you’ll understand why I’m taking this extended opportunity to celebrate their new album, released to commemorate their fiftieth year. Recorded in essentially one day, The Gainesville Session has the lived-in comfort and tight professionalism of a group of musicians who know each other well. Fiddler/vocalist Randal Harrison (who came aboard in the 2010s after Big Al retired) contributes “Whispers In The Morning,” a brooding stomp where Harrison’s fiddle and voice slide around Ken Baldauf’s banjo, and the steady thrum of guitar, mandolin, bass from recent addition (and co-founder of the Nashville Bluegrass Band) Mark Hembree. And, as throughout the entire album, the distinct syncopated washboard playing from Bill Kangaroo maintains a popping, dancing rhythm.

Harrison also leads “Jefferson Country Breakdown,” a Bob Mason original which the group previously recorded with Byla on their first album, a symbolic bookend and another the latest in a long line of fiery, fiddle-driven instrumentals that have become one of the band’s trademarks. The album boasts two co-writes between Mason and Shawn Camp, the acclaimed Nashville singer and songwriter who Bob has known and collaborated with since he moved to Music City in the early 1990s. They’re sung with wise sincerity by Barry Riese – the group’s original lead vocalist/guitarist who returned to the group in the 2010s – who also wraps his warm tenor around Michael Nesmith’s “Joanne,” a sincere and affecting nod back to the cosmic ‘60s. And it ends with a party, a loose-limbed take on “Deep Elem Blues” with Bob leading and directing traffic through an extended vamp that calls back to the traditions (“traditional” and otherwise) from which they emerged and sends The Gainesville Session out as the celebration it deserves.

Well, it doesn’t quite end there. Added to the end are two blasts from the past, a 45 from late 1978 that finds the group offering slightly gussied-up versions of two Bob Mason originals that they’d record elsewhere. It’s still disorienting to hear them with drums (!), but it’s a nice reminder (complete with popping vinyl left unedited on the digital transfer) of a bygone era that – thanks to their continued journey – doesn’t seem that far off. And which adds a chapter from right before I joined in.

I hope this isn’t the last new Piper Road Spring Band album, and I don’t get the sense that they plan it to be. But, regardless, it’s both a welcome summary of what’s come before and a fetching invitation to what might come next. As Bob’s original “Just Like a Dream” (maybe his best) suggests, the road may be long and the dreams may fade, but you can always “look back on what you learned.” I know I’ve learned a lot from them. Check out The Gainesville Session: it’s a fine record, a fitting summation of the group’s first half-century, and not a bad way to begin whatever’s further down the road for them. - CH

If you like what you’re reading here, please think of subscribing to No Fences Review! It’s free for now, although we will be adding a paid tier with exclusive content soon. Also, if you’d like to support our work now, you can hit the blue “Pledge” button on the top-right of your screen to pledge your support now, at either monthly, yearly, or founding-member rates. You’ll be billed when we add the paid option. Thanks!