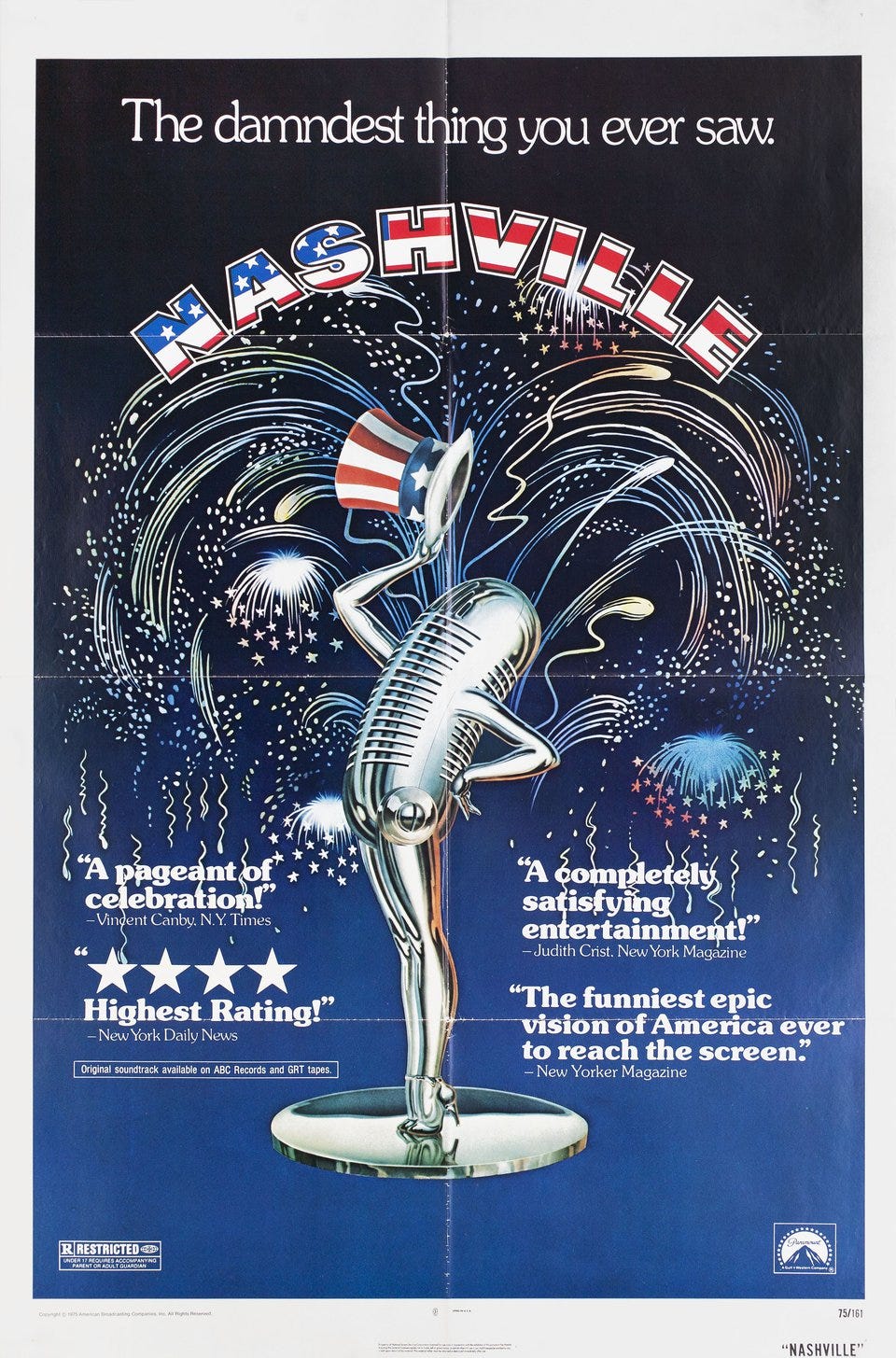

Nashville: Robert Altman's Film Turns 50

Charles and David go to the movies--and talk about it!

Be warned: This conversation is riddled with SPOILERS!

Charles: David, you and I recently saw Nashville as part of its 50th-anniversary screenings at Nashville’s wonderful Belcourt Theatre. You hadn’t seen it in quite some time, and it seems like it really had an impact on you. What were your reactions after revisiting this film after many years?

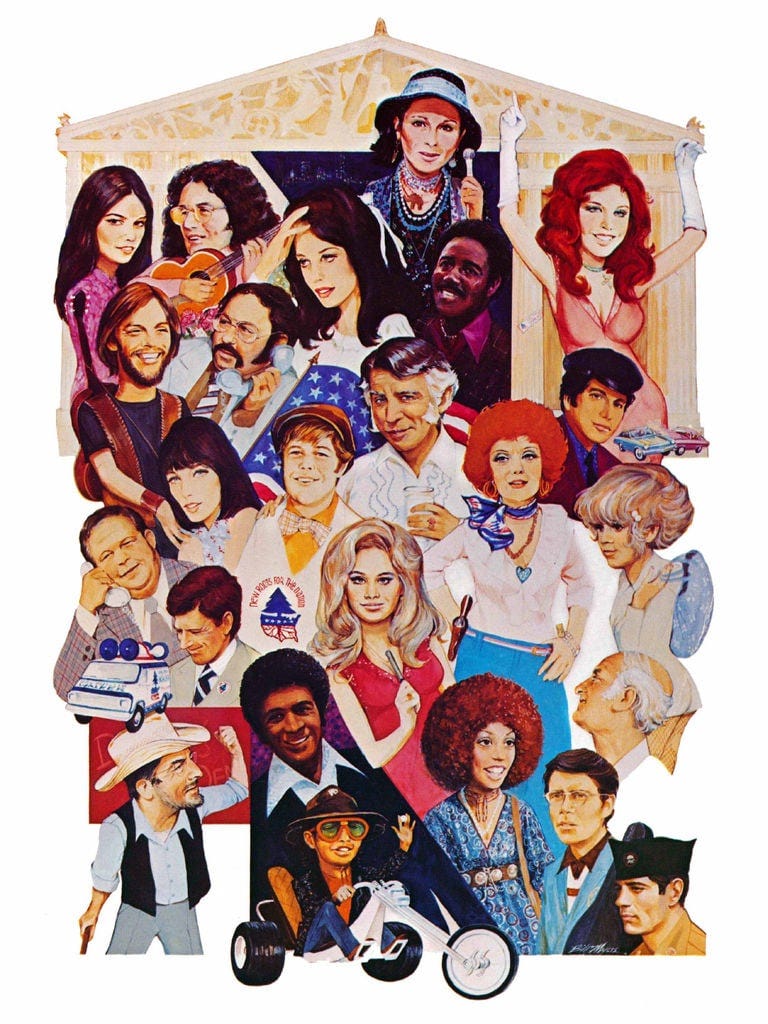

David: I’d only seen Altman’s film once before, on cable, maybe thirty years ago, and I didn’t really remember too much about it. This time, though, it hit me hard. I know the film is a kind of satire, as well as a singular sort of musical comedy, but my takeaway was the way it emphasizes just how lonely its characters are—and I guess just how such loneliness is endemic to American culture. Just about everyone in the film—the country stars, the would-be country stars, their fans, the politicians—all mask their loneliness by running around in a constant state of entrepreneurial frenzy. But the point in the film when loneliness as a theme snapped into focus for me was the quiet Sunday church sequence, Altman taking us from high church to low. It’s not played for laughs in the least, and at the end of it, the Keenan Wynn character leans over to tell the kid in the armed services next to him, unprompted by anything other than a need to connect, that his dying wife is staying on the same floor of the hospital where Ronnie Blakely’s country star character is staying. He wants so badly to feel connected to something larger than himself. So many of the characters are a little crazy, a little desperate, like that in their own lonely ways. Gwen Welles’ character, the terribly untalented wannabe country singer Sueleen Gay (whose hair and clothes somehow seem to be inventing Lana Del Rey decades too soon) is alienated from herself like that too. Barbara Harris’ Albuquerque character, who ran away from her husband to make it in Nashville, feels so alone throughout. At the end of the film, she’s up there singing with a black choir (the Fisk Jubilee Singers?) but singing mostly to herself and largely indifferent to their presence. Sueleen hugs a wall of the Parthenon and stares blankly. She humiliated herself for a chance at fame only to see her hero shot in front of her—and her shot at the big time killed too. What’s left of the horrified crowd gathers tightly together at the lip of the stage, traumatized by what they’d seen but also maybe just determined to get the show they came for. They shove in shoulder to shoulder but still each seem alone.

We could probably say a lot more about that ending, huh? I know you’ve seen the film many more times than I have, Charles–how did it hit you this time, in 2025?

Charles: I’ve seen Nashville so many times - it’s one of my favorite movies, and I return to it at least once a year if not more. But I’d never seen it in a theatre before, which made the Belcourt viewing so special. The big screen and powerful audio system added to the experience just in terms of size and scale: the way the sounds of the studio sessions and club scenes follow the camera across the room, the controlled chaos of those signature Altman ensemble set-pieces like the traffic jam or Haven Hamilton’s party; the striking appearance of the American flag across the entirety of the screen at the beginning of the climactic rally, et cetera.

David: If I’d been seeing it on a TV screen again, I know I would never have noticed that the book Barbara Jean has been reading while hospitalized is Faulkner’s Light in August!

Charles: Right! And hearing audience reactions was illuminating, too, especially the shifts from laughter to murmurs or even silence in the scenes where the mood transitions quickly. And I was even reminded just how quickly the film’s 160 minutes pass - I can get squirrely in a theatre even during great movies sometimes, but this was an eye-blink. Beyond that, I found the film to be newly powerful, hilarious, moving, provocative, and illuminating even after all my experiences with it. On recent watches, I’ve tried to focus on a couple of the characters as they move through this patchwork, and thus orient myself in what the film means with them at the (relative) center of the story. This time, I chose Geraldine Chaplin’s Opal (“from the BBC!”) and Keenan Wynn’s Mr. Green. An Opal-centered Nashville illuminates just how much the movie is about the perception of Nashville (and “Nashville”) as well as how Nashvillians from the powerful to the marginalized react to outsiders who move through the interlocking musical and political worlds symbolized by Barbara Jean’s return at the beginning and tragic participation at the Hal Phillip Walker rally at the end. Opal’s perhaps the most absurd and even offensive of the visitors - likening the Fisk-esque gospel choir to missionary work she saw in Africa, or pontificating about school buses in a junkyard - and Chaplin plays her with a perfectly comic (but also quite sad) kind of dizzy condescension. As you note above, Keenan Wynn lends Mr. Green a plain decency that offsets the scheming and dreaming taking place all around him. (The scene where he learns of his wife’s death catches me short every time.) And, of course, Gwen Welles’ performance is just masterful, right up to that devastating moment you describe in the final scene.

And yeah, the ending: many have talked about how it played in the U.S. of 1975, but how do you think it plays in the U.S. of fifty years later?

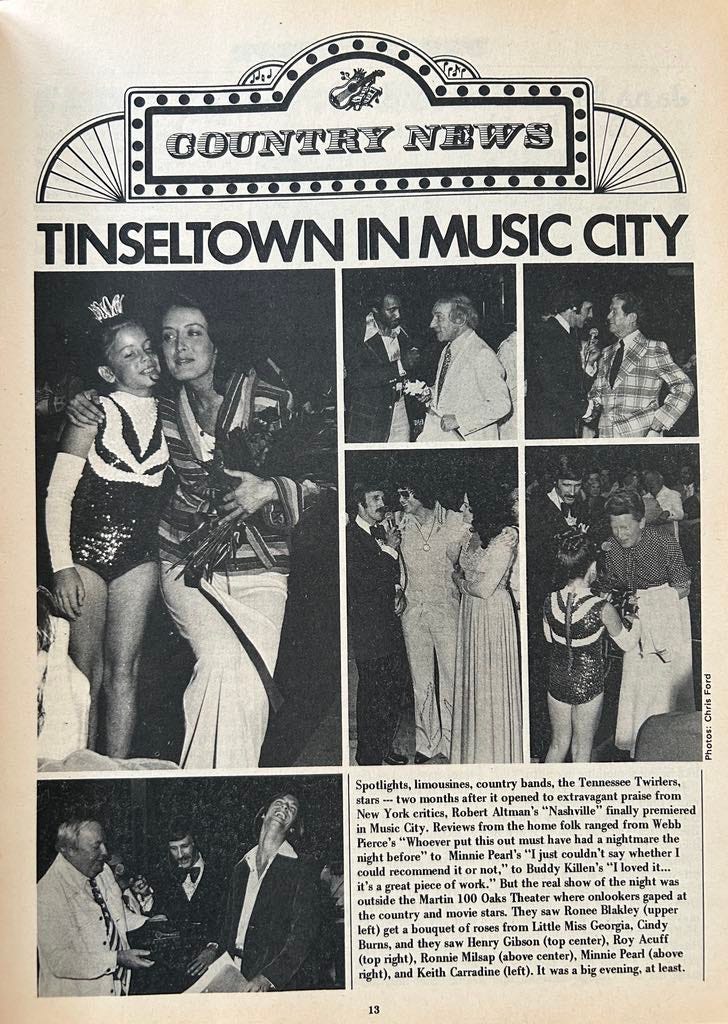

David: I guess there’s at least two ways to think about that. First, fifty years on, it’s so much easier to see the movie as a movie—and not to see it, as so many in Nashville did at the time, as an attack on country music generally and as mocking specific country stars. I pulled out some old copies of Country Music magazine to see how the film was covered in the moment. The longtime editor of the mag, Patrick Carr, liked Altman’s film very much: At the conclusion of a September 1975 piece, he praised the film and advised readers to “relax into the best movie ever made about country music.” At the same time, though, he reported that “Nashville seems to have put a few noses out of joint in Nashville” and, quoting from a Nashville Banner editorial, that “The movie… pictures country music entertainers as gushy phonies and portrays Southern lifestyles in less than complimentary tones.” A couple issues later, a brief report of the film’s Music City premier—both Nashville stars and Nashville stars were in attendance—documented takes from an annoyed Webb Pierce (“Whoever put this out must have had a nightmare the night before.”) and an at-least -trying to-be-polite Minnie Pearl (“I just couldn’t say whether I could recommend it or not.”)

At the time, too, there was some speculation that Ronee Blakely’s Barbara Jean character was a thinly disguised version of Loretta Lynn. In 2025, it’s obvious, at least to me, that her character is actually a composite of country’s biggest women stars in the moment: She does perform in a Loretta-style plantation dress but is also frail like Tammy Wynette and burbles cheerfully about her childhood a la Dolly Parton.

More directly related to seeing the film this year is the way Nashville seemed, at least in some ways, to anticipate our political moment even more than it reflected post-Watergate America. Campaign trucks with loudspeakers have given way to social media bombardment, but the faux folksy populist messaging of unseen presidential candidate Hal Phillip Walker—he heads the Replacement Party, is “for some replacing,” and runs on the proto-fascist slogan “New Roots for the Nation”—hit me as all too up to date as did the way a threat of political violence looms over much of the film. At the end, after the violence occurs, Albuquerque sings, “You may say that I ain’t free, but it don’t worry me.” That whole final moment of the movie teases a gospel impulse for collective change that we still desperately need, but that potential only teeters there before tumbling down–with freedom further away than ever and the characters feeling nothing but worry.

Let’s talk about the music in the film for a minute. The actors, while working with actual Nashville musicians, did their own singing and mostly wrote their own material. What’s your sense of how well or not the music worked in the film?

Charles: Nashville is one of the great movie musicals, sometimes not included next to more obvious classics like Singin’ in the Rain or West Side Story for the obvious (and fair) reason that the songs aren’t directly embedded in the film’s plot or character development. But the music is so crucial to both story and characterizations. You’ve talked about “It Don’t Worry Me,” and we could also include Haven Hamilton’s stilted bicentennial anthem “200 Years” (which opens the film) or Tom Frank’s “I’m Easy,” which captures his charm and indifference so perfectly as it drifts across reaction shots from Lily Tomlin and others. Or how the Opry sequence serves as a standalone segment in the middle, pitched somewhere between a concert film and a “dream ballet.” As a stylistic representation of mid-seventies Nashville country, it’s actually quite comprehensive in its range from acoustic folk-derived balladry to polished pop.

The quality of the songs and vocal performances? Mixed, which I know earned particular ire among a country-music community that thought it to be a poor representation of “Music City” standards. And, sure, Henry Gibson can’t sing. Although, as you pointed out, he’s not that far from Bill Anderson or others.

David: Yeah, country music is full of stars who lack what anyone would ever call good voices but who are still good singers because they commit to and sell the performance. Good singers sell performances–that’s what good singing is, good acting too I guess–and, in that sense, all of the actors playing country singers in the film come off as good singers, or at least good-enough ones, Gibson included.

Charles: Right. And none of the songs are jokey, at least not in a way that sticks out from what one might actually find on a “real” country record of the period. On this viewing, I was impressed by how many of the actor-written songs work better than they need to. Beyond Keith Carradine’s Oscar-winning work on “I’m Easy,” I’m particularly thinking here about Blakley’s “My Idaho Home” and “Bluebird,” the showcase for the (kinda sorta) Charley Pride stand-in Tommy Brown, performed by the actor Timothy Brown and written by Ronee Blakley. “Bluebird” has a real bounce and Brown’s voice is suited to the friendliness of the melody, and Blakley’s “My Idaho Home” captures the Lynn-Parton synthesis for the Barbara Jean character that you describe above.

[Here’s Ronee Blakely/Barbara Jean singing “My Idaho Home.”]

All of this is helped, of course, by the fact that the musicians backing these performances are various aggregations of Nashville pros. (My favorite musical moment in the movie might be when Karen Black as Connie White looks at the camera and says “here’s the best…here’s Vassar” as she introduces a solo by the great fiddler Vassar Clements.)

I know you have thoughts about the music, both in terms of the actors/singers/writers and the studio and live performers who back them up. What’s your take on the music? Any songs or performances stick out?

David: Ronee Blakely is so completely present as the mentally-on-edge country star Barbara Jean, particularly as she sings “Dues” at Opryland, that questions of artifice v. realism just faded away for me, replaced by “Ssshhh! Barbara Jean is singing!” I was really impressed with Henry Gibson’s Haven Hamilton, too, particularly his Grand Ole Opry set, which was nearly pitch perfect. Hamilton presents as a stand in for Hank Snow, another short man who liked rhinestones and sported unabashed toupees, but in terms of his unctuous stage presence, he reads more in line with Whisperin’ Bill, as we’ve said. Haven’s first Opry number, “For the Sake of the Children,” is cornball and condescending in ways that fit right into the C&W tradition –he’s moralistically telling his cheating lover that she can’t stay because he has three kids—but, and this how country music often works, the gesture of the song will also hit close to home for many. And, indeed, we soon see Lily Tomlin’s character leaving Keith Carradine’s bed precisely because she’s got to get back to her family.

[Here’s Henry Gibson/Haven Hamilton singing “For the Sake of the Children.”]

Later of course, it turns out Haven makes good on the facile positivity of his second Opry number, “Keep A-Goin,’” after the shooting goes down at the Parthenon. Finally, we open the film at a Haven Hamilton recording session, where he’s cutting an insipid patriotic anthem ahead of the nation’s bicentennial. It’s a classic country humble brag, as understated as it is prideful: “We must have been doing somethin’ right to last two hundred years.” The truth of that statement, including all of the questions it raises—Who is “we” exactly? What is this “something” we’ve done right? Will we last much longer?—just hangs over the violent finale in the same way that preposterously large U.S. flag dominates the frame.

Any other moments, Charles, musical or otherwise, that stood out for you?

Charles: There are always so many for me, but I’ll pick out a couple more before we close. First, to return to the great Gwen Welles performance, the way that Welles’ Sueleen Gay sings badly is just perfect. It avoids the humorous exaggerations or over-the-top irritation that so many “bad singers” have in movies, and instead convincingly suggests someone who thinks they’re good - and may have been told so by well-meaning friends - but truly lacks the talent that Gay thinks is going to take her to the top. (Although her songs - especially “I’ll Never Get Enough” - aren’t bad at all.) This matters so much as we follow Gay through the film, and makes our hearts ache for her all the more as her dreams fall apart. (It also gives both comic catharsis and real resonance to Robert DoQui as Wade Cooley in his final scene, when he urges his friend Sueleen to face reality before Nashville “kills you.” I hope she joins him on his promised departure for Detroit.) Welles does so much with the character, and this small touch is one of the most impressive. Second, I appreciate the way that the deafness of Lily Tomlin’s and Ned Beatty’s children becomes a pointed metaphor for the larger lack of communication between the family (city? nation?) without reducing the Reese kids to lazy “inspiration porn” tropes.

Finally, especially since I don’t think we’ve mentioned her yet, shout-out to screenwriter Joan Tewkesbury; although Nashville, like so many of Altman’s movies, was the product of much improvisation and collaboration, Tewkesbury wrote the original script, which was drawn partly from her experiences visiting the city in the mid-’70s, and helped develop the many characters that populate it. For all its baggy hangout vibes, the story is brilliantly structured, with characters crossing and re-crossing paths and themes emerging in sometimes surprising ways across its many scenes. Major props to Tewkesbury for building such a sturdy foundation and helping construct the many rooms that sit atop it.

Oh wait, one moreǃ I have to mention the work of Diane Pecknold, whose writing about the film and its contexts in her masterful The Selling Sound: The Rise of the Country Music Industry influenced my thoughts and observations about it, just as Pecknold has transformed my thinking about country music more generally. Given that we were in Nashville (in part) to celebrate Diane’s work at the annual International Country Music Conference, it seems fitting to end with some of her words, about the film’s sequence at the Opry:

“Altman’s quest for verisimilitude yielded an uncomfortably astute portrait of [country] audience and its self-conscious participation in country’s commercial enterprise…Looking into the lens, their staring eyes reveal both an awareness of their position as part of the entertainment commodity and a fascination, not with the down-home artifice of the performers, but with the spectacle of the commercial industry that provided so much of country’s fan appeal.”

I love Nashville, for all the reasons we’ve discussed here and many more. I’m really glad I finally saw it in a theatre, even gladder that it was Nashville’s great Belcourt, and gladdest of all that I shared the experience with you. Keep a-goin’.

David: A la Siskel & Ebert, I think it’s fair to say we give this movie two thumbs way up! Let’s make a point to go to the movies again sometime!

If you like what you’re reading here, please think of subscribing to No Fences Review! It’s free for now, although we will be adding a paid tier with exclusive content soon. Also, if you’d like to support our work now, you can hit the blue “Pledge” button on the top-right of your screen to pledge your support now, at either monthly, yearly, or founding-member rates. You’ll be billed when we add the paid option. Thanks!

I was going to sock this away for later but once I started I couldn't let go. One of the great American movies, and I need to watch it again immediately. Thanks, gentlemen.