Johnny Rodriguez, one of country music brightest acts for most of the 1970s and the genre’s first Mexican American star, died last month. He was 73.

Rodriguez’s movie star good looks and vocal charisma pointed, at first, to tremendous crossover potential. His earliest albums made Billboard’s Top LP’s & Tapes chart, and three early singles cracked the Hot 100. He appeared on an episode of Adam-12, was once a dreamy special guest on The Dating Game and performed on a country-themed episode of The Midnight Special while still promoting 1973’s “Ridin’ My Thumb to Mexico,” just his third single. “Ridin’…,” which Rodriguez wrote, became his second No. 1 and signature song.

Though he certainly had the voice and the records to crossover (check out his lush call on 1977 single “Savin’ This Love Song for You”), Rodriguez never saw the superstardom he seemed poised to achieve. Even so, he changed country music forever—though probably not for the reason you think. The lede in each of his obits (including mine above) justly proclaims his trailblazing status as the first country hitmaker of Mexican heritage. It’s the right call. Yet it’s important to note that, just as Charley Pride, the format’s first black hitmaker, didn’t burst down the door for other black country stars, Rodriguez’s success didn’t pave the way for other Latinx country singers on the radio. Freddy Fender, Johnny’s fellow south Texan, was an exception that proved the rule within an industry that made sure it would stay all but entirely segregated. In a piece published just this week, NFR’s good friend Jewly Hight, in conversation with Salvadoran American artist and Country Latin Association founder Angie K, reminded how “the country music industry treat[s] Hispanic artists as though they were interlopers in the genre, or like they were interchangeable, or ignore[s] them altogether.”

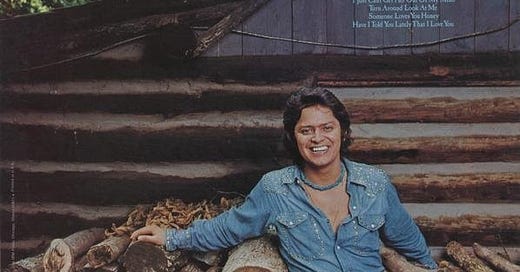

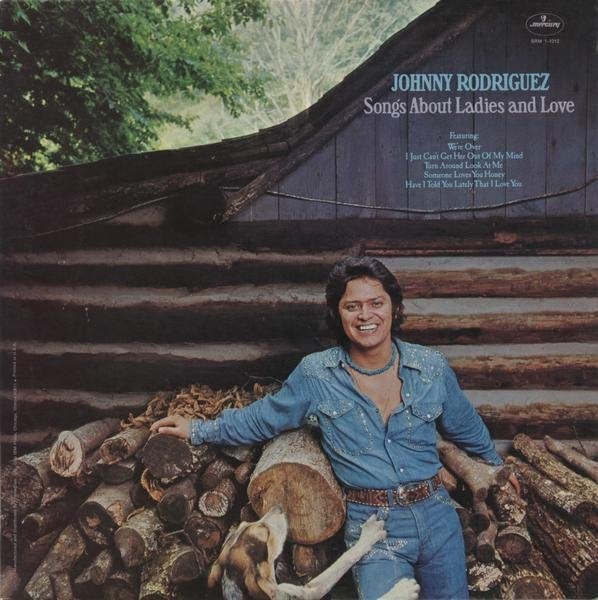

Rodriguez’s most enduring impact, then, alongside that of Tanya Tucker who he often toured with early on, was the foregrounding of a modern (read: rock) sex appeal that drew countless younger fans into the country tent.

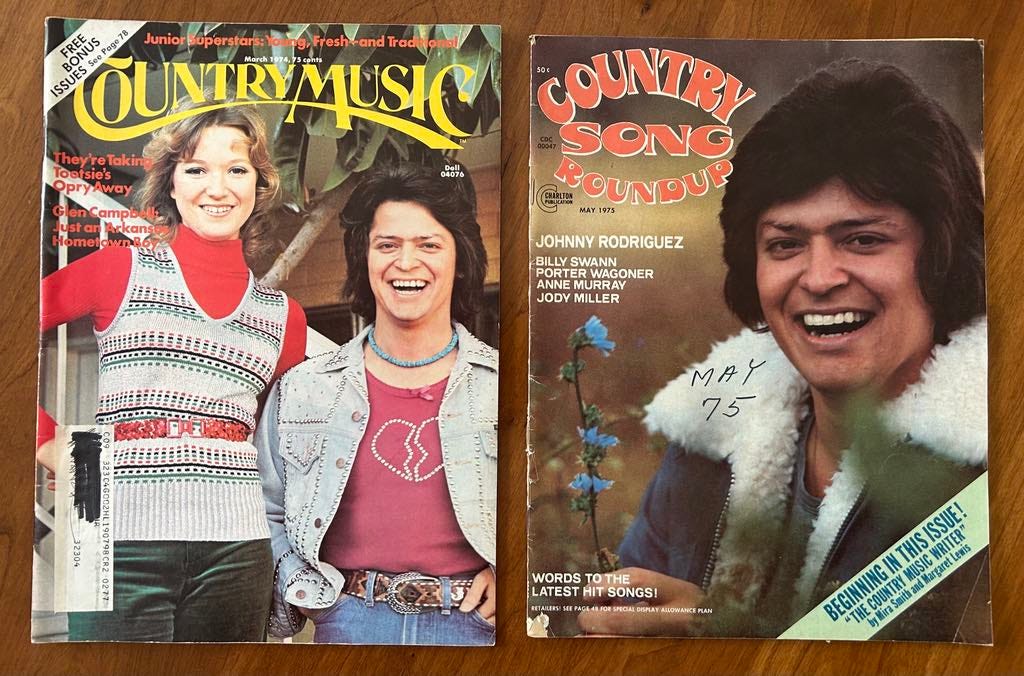

That was the lede in the day. For example, in the May 1975 issue of Country Song Roundup, a music journalist credited only as Micmarsus [Sic? Anyone know?] began a Rodriguez cover story, “Supermex Turns Superstar,” like this:

“When Johnny Rodriguez slides from English into his mellow Spanish mid-song, the women of the audience slide a little further off the edges of their seats, craning their necks and oohing and aahing all the while. Rodriguez, whose legion of teen and female followers is fast approaching the numbers experienced by pop artists, has a distinctive style that strikes a responsive chord to a wide variety of listeners. Most of his music is solid country, but his appeal is universal.”

A chunk of the story is then devoted to tales of the many times horny young women mobbed him after shows—and even during them. “When I was retrieved by the security people,” Rodriguez recalls about one scary incident, “my shirt was torn, I had some bruises, and I was scratched up pretty bad.”

Billboard began a 1973 report, “Johnny Rodriguez Posing New Country Teen Pull,” this way: “A five-foot eight-inch Mexican American, Johnny Rodriguez… may well prove to be the youth shot-in-the-arm country music has long sorely needed, if early indications bear out.” A year later, in Country Music magazine, a J. R. Young-penned cover feature, “How Come the Kids Are into Country? Tanya Tucker and Johnny Rodriguez… That’s How Come,” attempted to suss out Rodriguez’s appeal: “Face it. It’s difficult for an eleventh-grade girl to fall giggly in love with Johnny Paycheck… But if you’re young and lovely and you can dream of Johnny Rodriguez… well, that’s something else again. Yes indeed, and it is happening all over the country, and to girls who may have never listened to country music before.”

There was a key difference in the way Tucker and Rodriguez performed their sexual appeal. Tanya the “Teenage Teaser” (as she was dubbed in a 1974 Rolling Stone cover story by Chet Flippo) rocked her hips and strutted rhythmically about the stage like her hero and chief role model Elvis Presley. Johnny tended to stand stationary, or even to sit and strum, during performance a la his main man Merle Haggard. Even so, sensuality oozed from his bright smile, his smoldering vocals, and a head of hair many women, and men too, wanted badly to run their fingers through. Along with Puerto Rican American star Freddie Prinze, Rodriguez was an early Latino sex symbol within seventies pop culture generally. While I was researching this piece, my wife, who was unfamiliar with Rodriguez, asked me why I was spending so much time looking at pictures of Erik Estrada, a slightly later Teen Beat-heartthrob. I guess what I’m trying to say is that Johnny Rodriguez was a smoke show. Going forward, country music would develop an ever-increasing preference for those.

But wait, there’s more. Besides being a hunk, Johnny Rodriguez was a fantastic songwriter and among the genre’s greatest vocalists, however underrated and overlooked he is today. He was born in Uvalde, Texas, in 1952, the eighth of his parents’ nine children. Uvalde was a south Texas hill-country town where Anglos and Chicanos were in many ways segregated but were tightly intermingled in others: Young Johnny grew up bilingual, linguistically and culturally, an approach he adapted to his singing and song selection. He formed a rock and roll band in his teens, and though we don’t know exactly what they played, the handful of old rockers he covered on his albums over the years seems likely to wave at the younger man’s setlists: “C. C. Rider,” “Will You Still Love Me Tomorrow,” “You’ve Lost that Loving Feeling,” “I Fought the Law,” “Down in the Boondocks,” “Don’t Let Sun Catch You Crying,” “Stagger Lee.”

In an oft-repeated tale, Rodriguez was arrested for goat-rustling in high school and, while in lockup, was overheard singing by an appreciative Texas Ranger who hooked him up with the owner of an entertainment complex called Alamo Village, where he was promptly discovered by Tom T. Hall. In truth, as Bill C. and Ann Malone documented as early as 1975 (in The Stars of Country Music: Uncle Dave Macon to Johnny Rodriguez, edited by Bill Malone and Judith McCulloch), this tale is as much P.R. creation as biography: It conflates arrest episodes, telescopes years into weeks and omits that Rodrieguez went to jail while his accomplices didn’t because, as the Malones hint, he was brown and they were white. In any case, Tom T. did hear him perform, encouraged him to move to Music City, and promised to do what he could to help him get started—with the caveat, according to Ken Burns collaborator Dayton Duncan, that he had to lose the stage name he’d adopted, “Johnny Rogers.”

Johnny Rodriguez wouldn’t take Hall up on the offer for another year. But when his father and his older brother died in close succession (his “Jimmy Was a Drinking Kind of Man” was partly inspired by returning home for his brother’s funeral), Johnny quit his construction job and headed to Nashville. Hall hired him more-or-less instantly to play guitar in his band the Storytellers. He also made the introductions that got the nineteen-year-old signed to Hall’s label, Mercury, and he wrote “You Always Come Back (to Hurting Me)” with the kid. That cowrite became a chart topper, Rodriguez’s first.

He had five more of those over the next few years, alongside fourteen Top Ten country hits. That chart run, combined with the way he prefigured a young country audience the format has largely been built upon ever since, plus his role as the genre’s first major Mexican American star, should make him a no-brainer for the Country Music Hall of Fame. (2024 inductee John Anderson, for example, notched one fewer No. 1 than Rodriguez and just one more Top Ten.) Now, I don’t expect Rodriguez to be inducted for several reasons (not limited to racism though don’t minimize that factor either). But he should be.

Of course, the final part of his case for induction, and for your listening time, comes down to his being so damn good for so long. To begin making that point, I’ve written about a half dozen of my favorite Johnny Rodriguez songs—and cite several more of his best sides, too, along the way, while also pointing you in the direction of what I’m calling his three (at a minimum) masterpiece albums. One of my picks is obvious, the rest much less so—Rodriguez has a deep catalog. (If you don’t already know 1975’s The Greatest Hits, or some best-of equivalent to, I’d start there.) But all of my choices, even the TV appearances I’d argue, are essential to any serious consideration of the best in country music from the 1970s into the ‘90s. These few selections are hardly definitive. But as country singers go, Johnny Rodriguez was about as definitive as it gets.

“Down on the Rio Grande” (from Pop! Goes the Country, 1979)

The song is a Rodrieguez original, his Top Ten debut single for Epic Records (produced by Billy Sherrill) after his career-defining run at Mercury. Here’s the excellent Billy Sherrill produced studio version of the song, but I’ve chosen to highlight this TV appearance from around the same time because it really lets you see his particular charisma: The way you can’t take your eyes off him even though all he’s doing is just sitting there and also the way he is clearly both a smiling entertaining and an in-the-emotional-moment performer with strong pop singer-songwriter vibes. Just a rock star.

“That’s the Way Love Goes” (from All I Ever Meant to Do Was Sing, 1973)

The first single from his second album, his chart-topping signature hit “Ridin’ My Thumb to Mexico,” balances sunny optimism and what-else-you-gonna-do fatalism in a vocal attack that makes clear that all those folks who called Rodriguez a Chicano Charley Pride weren’t just lumping the singers together racially. He wrote that one as he did “I’ll Just Have to Learn to Stay Away from You,” a great deep cut from the same album. It’s a testament to what a strong songwriter Rodriguez that he was quickly sharing material with the best of the best. “Me and Merle Haggard and Lefty Frizell and Whitey Shafter and Dallas Frazier and Lewis Talley were all sitting in a motel room in Nashville called the Continental Inn one night,” he recalled to journalist Tom Roland: “We’d been playing songs to each other, and the very last song of that night, Lefty was fixing to go home. He said, ‘I got one more song I want to play…’ Merle wanted to cut it, but he’d just finished doing an album.” That’s how Rodriguez became the first to cut the famous Lefty and Whitey co-write. (Haggard eventually scored a hit with the song himself, in 1983.) “That’s the Way Loves Goes” became Rodriguez’s third No. 1 in a row, and I share it because it helps us hear how Johnny was indeed influenced, vocally, by Lefty and Merle but also how he was his own man. In a lullaby version that doesn’t even last two minutes, he eschews the melisma his heroes often deployed, and, though singing comfortably, comes off as if he’s pushing himself toward the top of his range—the subtle effect is to heighten the stakes. He’s not just grateful for his lover’s support. He has to let her know he needs her.

“Ramblin’ Man” (from My Third Album, 1974)

Conventional wisdom is that Rodriguez’s first two albums are his best but don’t be turned off his third set by its uninspiring title. His originals are excellent: “Dance with Me (Just One More Time)” was a No. 2 hit and “Bossier City Backyard Blues” is, in part, a tribute to old boss Tom T. Hall. His covers of country classics “Born to Lose” and “The Last Letter” are haunting while his mildly controversial Top Ten cover of “Something,” so humbly romantic, is one of the best versions of that oft-covered George Harrison song I know. That choice, too, underscores that one of the ways Rodriguez changed things was by expanding the country-music repertoire with rock material. He later recorded the Eagles’ “Desperado,” a Top Ten hit pulled from an album that also included his take on “Lyin’ Eyes,” and over the years he cut “Fire and Rain,” “Bridge Over Troubled Water,” “To Love Somebody,” Gordon Lightfoot’s “If You Could Read My Mind” and Randy Newman’s “Marie.” Here, his version of the Allman’s “Ramblin’ Man” brings southern rock seamlessly into the country fold—a good two years before Hank Jr. started cutting Toy Caldwell songs. Old school A-Teamers Bob Moore and Buddy Harman prove they can get country funky as you like while horns push things south of the border and, God help me, whoever lays down that fiddle solo improves on Dickey Betts. Johnny, meanwhile, really makes you believe he regrets hitting the road again at least as much he’s bragging about it: “I hope you’ll understand…”

“The Immigrant” (from Just for You, 1977)

Among so many other accomplishments, Rodriguez also must be counted among Merle Haggard’s greatest interpreters. He cut a number of the Hag’s songs throughout his career: “I Take a Lot of Pride,” “Somewhere Between,” “If I Left It Up to You,” “Love and Honor.” His version of “The Immigrant” is his most remarkable. As I discuss at length in my Haggard book, the song, which Merle wrote with his guitarist Dave Kirby, could certainly be better: “Merle turns his own version into an unaccountably jaunty sing-a-long” and “You wish Merle’s selection of Spanish rhymes and immigrant motivations (‘Take home dinero and buy new sombrero’) weren’t as impoverished as the immigrants he's singing about.” Still, “The Immigrant” is an endorsement of Mexican immigration and a full-throated condemnation of the U.S.’s exploitation of their labor, even noting “that it was rich gringos who stole ‘land from the Indian man way back when’.” But for sure Rodriguez’s version is the one you want. Closer to his subject, he “sings his version as a plaint, borderline embittered and beautiful because of it.” “Border patroller, don't stop the stroller,” Rodriguez demands. “Cause the Mexican immigrant is helpin' America grow.” Turn it up.

“Deportee (Plane Wreck at Los Gatos)” (from Hee Haw, ?)

What an honor that Johnny Cash, Waylon Jennings, Kris Kristofferson and Willie Nelson tagged Rodriguez to guest with them on their 1985 supergroup debut. But what the fuck they didn’t just ask him to join the group. This TV version, from some episode late in Hee Haw’s run, is even better, I think, because it’s a tad slower, because it’s all Johnny Rodriguez, and because he makes the still-on-point point of singing it in first person. “Some of us are illegal and others unwanted… They chase us like rustlers, like outlaws, like thieves…”

“Corpus Christi Bay” (from You Can Say That Again, 1996)

In 1996, a decade or since his last Top 20 hit, and nearly fifteen since his last Top Ten, Rodriguez released a kind of comeback album, You Can Say that Again, for the indie label Hightone. The entire disc is fantastic and was the direct inspiration for many alternative country types, me included, to track down his classic Mercury albums. Working again with Jerry Kennedy, his producer back then, he sings Merle Haggard and Whitey Schaefer numbers just as you’d figure he would but also kills on songs from Lucinda Williams (“Big Red Sun Blues”) and Dave Alvin (“Every Night about This Time”). He absolutely slays Robert Earl Keen’s “Corpus Christi Bay.” Is that tremor in his voice ambivalence about life choices he thinks he couldn’t have changed if he wanted to—or is he just fighting off the shakes before the day’s first drink? Next year, when I tally my picks for The Best Country Albums of 1996, I guarantee this one will near the top of the list.

R.I.P., Johnny Rodriguez. Put him in the Hall of Fame!

If you like what you’re reading here, please think of subscribing to No Fences Review! It’s free for now, although we will be adding a paid tier with exclusive content soon. Also, if you’d like to support our work now, you can hit the blue “Pledge” button on the top-right of your screen to pledge your support now, at either monthly, yearly, or founding-member rates. You’ll be billed when we add the paid option. Thanks!

Like Earl Thomas Conley, another great that everyone conveniently forgot about. Thanks for this. And thanks, Johnny ❤️

Thanks for acknowledging his HighTone album. It was co-produced by the great Roy Dea. I gave Roy the songs by Lucinda, Dave Alvin and REK for Johnny to record and he killed. I have said for years that Corpus Cristi Bay is my favorite rrack that we released in HighTone—as country as it gets.