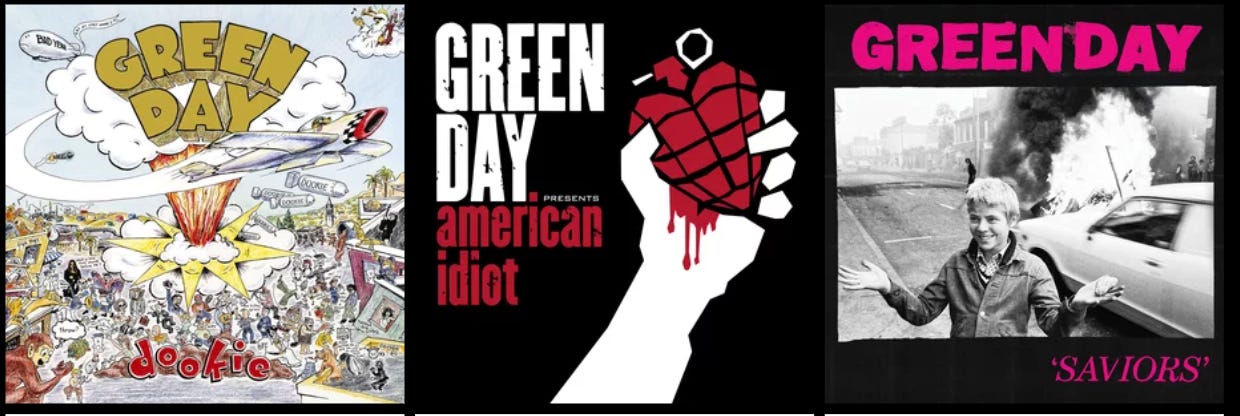

Green Day: Dookie, American Idiot, Saviors

Charles Hughes on three albums from the band's past and present

Green Day has been with us for 37 years. The fact that the Bay Area goofballs who mixed punk grime and MTV glam at the height of Alternative Nation to such popular (and initially controversial) effect have managed to become such lifer rock ‘n’ roll heroes really shouldn’t be that surprising. Combining the lessons of the Clash and the Ramones, they’ve always been adventurous classicists in both influence and form. Drawing from AM radio pop-rock as much as many of their punk forebears did, they’ve always centered sturdy songcraft and big-hearted gestures. And they’ve always espoused a seemingly sincere belief in the enduring and liberating power of rock ‘n’ roll.

It’s a big year for the band, still composed of Billie Joe Armstrong, Mike Dirnt, and Tre Cool. Dookie celebrates its thirtieth anniversary this month, American Idiot turns twenty later this year, and they’ve got a brand new record called Saviors. They’ll tour that new album in a stadium run this summer, where they’ll also play both anniversary albums in their entirety. These linked milestones, and the band’s seeming desire to place them in conversation, offers a good chance to consider them together. So let’s rock.

Dookie (1994)

There aren’t many opening lines that capture a vibe and sensibility better than the self-aware, slight-smirk question at the start of “Basket Case”: “Do you have the time to listen to me whine about nothing and everything all at once?” But the power-drive of “Basket Case” captures the album even beyond this microcosmic lyric. Dookie is all big feelings and big hooks, an overdriven bubblegum blast where almost every song is about growing up (whether to, how to, why to, at what cost) and structured around a massive chorus. There’s plenty of no-future rumination here: sickness, angst, and desperation fueled by factors both internal and external. There are “broken homes” and unfriendly streets, boring lives and sexual frustrations. But, even at its scuzziest, Dookie is never a soundtrack of negation. Sure, Armstrong tosses off sentiments like “to me, it’s nothin” or “fuck off and die” to suitably impertinent effect, but he never really sounds convinced of this easy nihilism. Rejecting the lazy stereotype of punk as disaffection and embracing instead its ethos of rock ‘n’ roll as an engine of community, they’re too invested in “Having a Blast” (the title of my favorite Dookie deep-cut), even as they also recognize, as in that song, that “no one here is getting out alive.”

Dookie sounds like they’re having way too much fun to stop now. It wasn’t their debut, but the record sounds like a band discovering just how good they could sound remixing their influences around such jubilant hooks and sledgehammer arrangements. “Longview” is Kinks-to-Buzzcocks horndoggery with a fittingly ejaculative hook and a repeating riff that owes as much to KISS as anyone else. “Chump” ends in a clatter of Who-style guitar windmilling and drum cacophony. “Pulling Teeth” brings together Fab Four harmonies and chiming Byrds guitars. The blooming power-pop of “She,” built around Dirnt’s rapid-heartbeat bass and soaring high harmonies, uses Armstrong’s invitation to “scream at me until my ears bleed” as a generous inversion of the question at the opening of “Basket Case,” which directly precedes it. The album’s biggest hit, “When I Come Around,” skips along with the nervous rush of the song’s young-lover protagonist in a post-Operation Ivy groove that anticipates the SoCal and ska-revival bands about to flood the pop zone.

The album starts to blur together near the end. (There’s a reason why Tre Cool’s bonus-track goof “All by Myself” is the most famous song of the album’s final third.) It’s nowhere near perfect and there are better albums from this moment of tuneful punk breaking into some version of the mainstream. (Rancid’s …And Out Come the Wolves is still my pick for the masterpiece.) But Dookie owes its endurance both to the fact that its songs remain such sustained, sustainable pop-rock gems and because, despite the band’s early mud-chucking impertinence, the little snots figured out a way to grow up.

(Interlude 1: I was a junior in high school when “Good Riddance (Time of Your Life)” came out, which means that I was in the epicenter of its use as an anthem of instant nostalgia. And in that moment, before the song became the bane of every open-mic and dorm room, the song felt like a poignant glimpse of a coming transition, both in terms of its good-luck-and-goodbye lyric and in how its acoustic guitar and washing strings signaled a new facet of Green Day’s musical interests. Calling it a new “maturity” both would and would not be bullshit. What I’ll call it instead, especially now that “Good Riddance” has cuddled up into its role as canonical oldie and tear-jerking encore, is something like a sonic recognition of how one could hold the past and the future simultaneously in one small, sweet moment. Sing along – you know how it goes.)

American Idiot (2004)

At the end of 2023, Green Day performed on a New Year’s Eve TV show. During their rendition of the rushing title track from this smash album, Armstrong altered the lyric from not wanting to be a part of the “redneck agenda” to instead denying the “MAGA agenda.” There was the predictable reaction from right-wingers who clearly hadn’t been paying attention in the same way they haven’t paid attention to songs by Bruce Springsteen, Rage Against the Machine, and so many others. But beyond that, this incident offered a welcome reminder of just how scathing American Idiot sounded when it emerged in the year of George W. Bush’s re-election. In that bleak time, Green Day eschewed irony or subtlety in favor of a full-throated, full-throttle state of the nation. As both a statement and a listening experience, American Idiot is a scream.

It doesn’t hide its ambitions: a rock-opera narrative focusing on a central character, the Jesus of Suburbia, whose personal turmoil is mirrored and accentuated by the societal tumult that surrounds him. Like most such things, the storyline gets a bit weedy down in the details. But, like the best such things, Green Day doesn’t let the storyline get in the way of other lines – guitar, melody, rhythm – that matter far more. The reliably gigantic choruses are cranked up here even further than before, matching both the heavyweight subject matter and a mix that pushes the sound right down your throat. And even the slightest songs are anchored by a memorable hook – or, in the multi-part tracks that stretch out sometimes into nearly 10 minutes, several memorable hooks. This marriage of pop and prog sensibilities might’ve earned some snickers at the time, but – as grandiose as it is and aims to be –American Idiot never gets swallowed in pretense or ponderousness. When it’s really working (as it is almost all the way through its 58-minute runtime), the hooks amplify the galvanized, angry spirit at the songs’ core. They attach melodies to great lyrical ideas – the way Armstrong’s voice falls into resignation at the end of “In the land of make believe that don’t believe in me,” the circling “I don’t care if you don’t care” and the escalating, Tre Cool-driven punch of “I leave behind the hurricane of fucking lies,” and those are just in the early track “Jesus of Suburbia” – and the varying lengths allow them to get in and out for just as long as individual songs (or segments) require. The obvious influences are there – Clash, Ramones, British Invasion – along with touches of everything from girl-group pop and surf rock to invocatory tablas and arty chorales.

Amidst this rush of sound and fury are several centerpieces. “Boulevard of Broken Dreams” and “Wake Me Up When September Ends” – power ballads that pull off the neat trick of being simultaneously bombastic and tender – return to their favorite theme of the search for oneself in an alienating world, this time fueled less by angsty self-involvement and more by the contexts of an imprisoning society. Then there’s “Holiday,” the slashing track that most directly attacks the War on Terror and – like the album more generally – cracked through into the mainstream during the height of support-the-troops censorship. (I remember well talking to several frowning Boomers in this period who claimed that there was no anti-war music coming from this generation. In other words, my generation. Beyond the hundred other reasons why they were wrong, I always asked if they knew that Green Day had a Top 20 hit with the lyric “Sieg Heil to the President gasman/Bombs away is your punishment!” They did not. People try to put us down.) Like most of American Idiot, “Holiday’s” cry of “I beg to dream and differ from the hollow lies” isn’t necessarily nuanced, but its desperate insistence felt right then and still does now.

Like Dookie, American Idiot flags a bit at the end. There’s nothing wrong with The Who riffs and Rocky Horror pastiche in the suite “Homecoming,” but it may just be that the combined weight of all these crash-bang rockers can’t help but start to lose a little impact after nearly an hour. And after the rousing, shouted close to “Homecoming,” the album ends with the mid-tempo atmospherics of “Whatshername,” a move that makes sense if you know the plot, but ends this very dramatic album on a somewhat anticlimactic note.

American Idiot felt important at the time, especially when it became a huge hit. Whether it actually was important is debatable. But I reckon that it sounds even better now than it did when it came out – it remains explosive and epic, and its specific pleasures haven’t dulled one tiny bit. Plus, as evidenced by the reaction to Armstrong’s altered “American Idiot,” it still has the potential to piss off the right people. For a rock ‘n’ roll song nearly old enough to drink legally, that’s not bad at all.

(Interlude 2: In 2005, I saw Green Day on the American Idiot tour, accompanied by two people my age and one friend who’s a few years older. We were easily the oldest people in our section, other than the parent/guardian-types accompanying their tweens and teens. The crowd was amped the whole time, but there was a noticeable difference in the excitement of the younger fans for all the American Idiot tracks versus their excitement for the band’s older songs. And that made total sense: it was nice to see this band from our heyday - *sob* - connect with a new group of fans just entering theirs. And despite the generation gap enacted around us, my 23-year-old ass, my friends’ 23-year-old asses, and our friend’s 40-something-year-old-ass were on our feet for every reminder of how these reinvigorated arena heroes got their start. Did we get some strange looks from the kids when we shouted along to “She,” “Hitchin’ A Ride,” and even hits like “Basket Case?” Maybe. Did we feel old? Yes. Did we care? Not one fucking bit.)

Saviors (2024)

The little snots have still got it. Saviors loses none of the bombastic, anthemic fun that unites Dookie, American Idiot, and nearly every element of their discography. In the twenty years since American Idiot, they’ve taken big swings (the even more rock-operatic 21st Century Breakdown, the Broadway version of American Idiot) and come back to their scrappy roots (the three-part Uno! Dos! Tre!, the return to form of Father of All…). Throughout, they’ve both cemented their status as elders and offered some admirable (if not always successful) attempts to destabilize their legacy phase. The new Saviors works on each of these registers, and proves that – whether big or small – Green Day is still coming out swinging.

They haven’t lost their nerve. “The American Dream Is Killing Me” is a shotgun dropkick that recalls The MC5’s similar call to arms “American Ruse” as much as it evokes American Idiot’s title cut. Like the mirage described by the Detroit rockers, the dream here is both a fallacy – as evidenced by the unhoused and unemployed – and a burden. (I find it both noteworthy and unsettling that this song is coming out 20 years after “American Idiot” sounded the alarm about Bush’s re-election, as we all stare down the real possibility that the “MAGA agenda” will be sent back into power in November.) The urgent, Clash-esque “Coma City” notes that “they bankrupt the planet for assholes in space” while ignoring the epidemic of gun violence. They even offer a future-shock double-shot of “Strange Days Are Here to Stay” and “Living in the ‘20s,” but helpfully avoid “good old days” grumbling as they settle into middle age.

They also haven’t lost their verve. “Look Ma, No Brains!” is joyous, self-deprecating nonsense. The stomping “Bobby Sox” describes a love that alternates between sweet-voiced coos and bratty shouts to fine and funny effect - Armstrong, who came out as bisexual in 1995, performs the dialogue equally plausibly as two voices or one fluid protagonist. (The video makes this even clearer.) “Dilemma” spins a “Basket Case”-style opening invitation into a deeply serious (and no less compelling) take on alcoholism. “Suzie Chapstick” is jangly power-pop longing, a broken-heart corollary to two of the most directly nostalgic songs the group’s ever recorded. “1981” pays hurtling tribute to a music fan who “bangs her head” and “throws punches to the beat” next to era signifiers of cable TV and the Cold War. The Cheap Trick-recalling strut of “Corvette Summer” is even better, befitting its classic-rock title and big-ass riff with a chorus that recalls the Beach Boys (“I can get around”) before promising to do things – “fuck it up with my rock and roll” – that suggest a punkier generation of surfer kids. As with the crassness of Dookie, there’s always a barely concealed sweetness in Armstrong’s cocksure delivery, especially when he sings here that he’ll be okay if only someone will “take me to urgent care or the record store.” At this point, friends, even my pure rock ‘n’ roll heart has very limited space for any more crunchy songs about how this music will set you free. But the snap-crackle-pop of these two are undeniable.

Like Dookie and American Idiot, Saviors falls off a bit in the home stretch. “Father of a Son” is a lovely idea, but it’s a bit goopy compared to the rest, and the same goes (to a lesser extent) for the Oasis-trionics of the title track that follows it. (In fact, I think it’d work better with the Gallaghers doing it and I’m not kidding.) But, just as “Basket Case” set the thematic table way back when, I can’t imagine a better summation for this point in Green Day’s career than the startling central line of closer “Fancy Sauce”: “We all die young someday.” In context, the line may be a declaration of live-fast fatalism, I guess. But – almost forty years in – it feels like the band is reminding us that life can and should be as sweet, joyous, and fleeting as a great three-minute rock ‘n’ roll song about nothing and everything all at once. I’m sure glad they didn’t die before they got old. Or before I got old. Because now, God willing, we’ll get to do it together. Rock on.

(Postscript: I tried to figure out a way to include stuff in here from Niko Stratis’ brilliant piece about Green Day and queerness, especially in light of the aforementioned “Bobby Sox” video and Armstrong’s recent statements in support of trans rights. But instead of sprinkling in a few references, I’ll just tell you right now to go read the whole fucking thing.)

Thanks to Brian Bischel, Kevin & Erica McCool, and Eric Schumacher-Rasmussen, who still know all the words. - CH

If you like what you’re reading here, please think of subscribing to No Fences Review! It’s free for now, although we will be adding a paid tier with exclusive content soon. Also, if you’d like to support our work now, you can hit the blue “Pledge” button on the top-right of your screen to pledge your support now, at either monthly, yearly, or founding-member rates. You’ll be billed when we add the paid option. Thanks!

BTW - great piece Charles!! Keep up the good work!

Dookie is a critical album for a number of other reasons beyond its sonic impact. Green Day emerged from a ROBUST East Bay punk scene in California that was rife with talent and very well developed DIY venues and bands. Originally called 'Sweet Children,' it was fairly obvious to everyone involved that this trio was meant for great things. Dookie's release in 1994 marked the full ascent of this underground scene to mainstream audiences, a process set in motion by fellow west coast rockers Nirvana with the release of Nevermind in 1991. By 1994, punk had gone mainstream - from 924 Gilman Street to selling our stadiums around the globe. Green Day both rode the wave that Nirvana launched and forged new commercial pathways for a host of bands that followed in their wake. And punk / underground music would never be the same, for both better and worse. From the perspectives of the underground activists who forged the scenes that incubated Green Day, this shift was not great. Green Day was ultimately banned from playing their local 'home' club 924 Gilman, and East Bay contemporaries Jawbreaker would pay a similar price with fans when their major label debut "Dear You" was released a year after Dookie in 1995. There is a great documentary on this history, produced by Billy Joe Armstrong, called "Turn It Around: The Story of East Bay Punk."