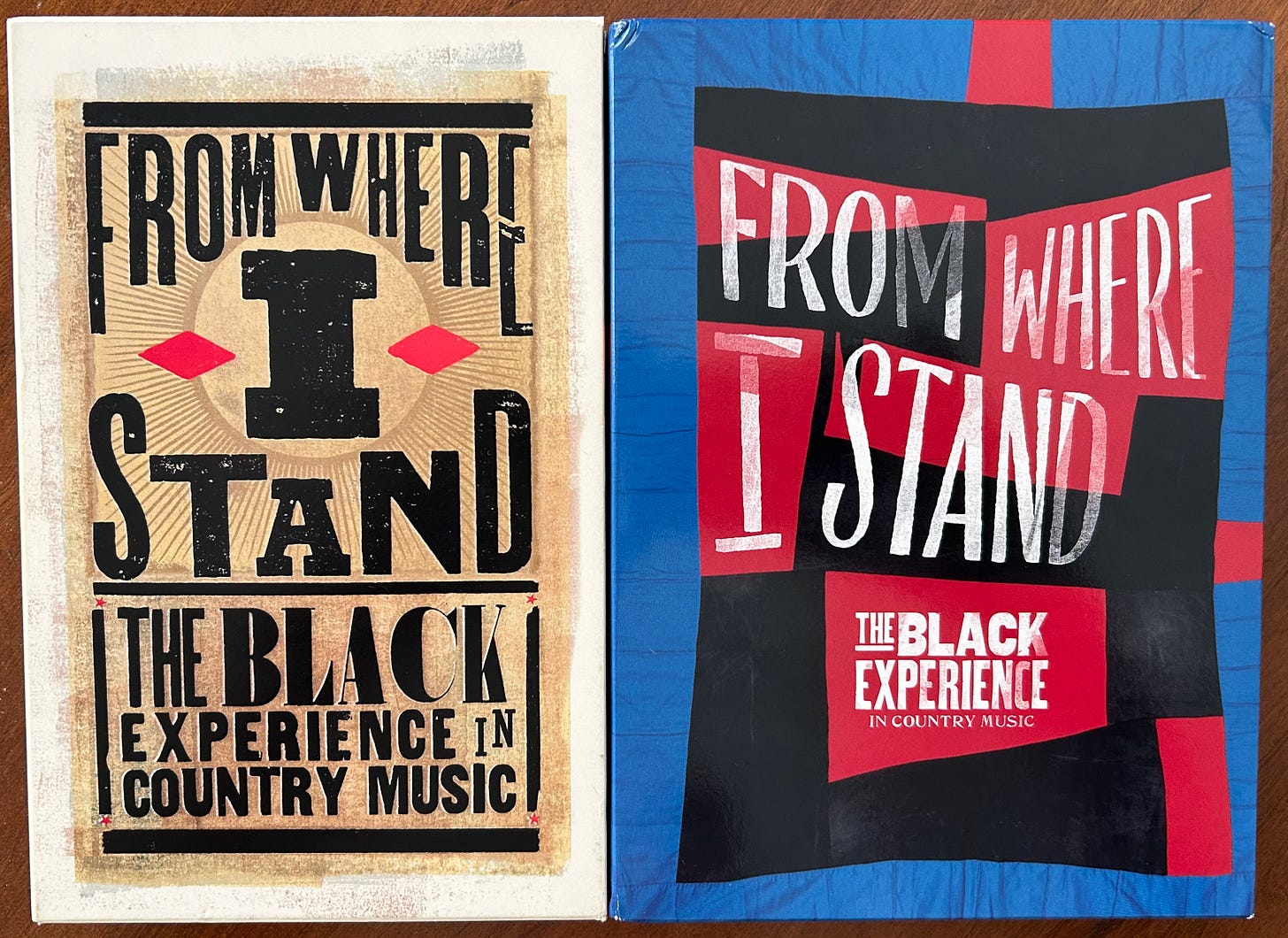

From Where I Stand: The Black Experience in Country Music

David considers the reissue of a classic country music box set--and wonders where we go from here

From Where I Stand: The Black Experience in Country Music, a three-disc box set first released in 1998, goes on the short list of essential country music compilations because it was a game changer. The role of Black musicians in country music—as influencers, as ongoing participants, as foundational creators—had been standing right there in plain sight since… forever. Typically, though, the Black experience in country music didn’t get mentioned at any greater length than I just summarized it in the previous sentence. Toss in a quick nod to Charley Pride, DeFord Bailey or Rufus “Tee Tot” Payne and, for far too long, you were good to go. From Where I Stand helped to change that.

Back in ‘98, remember, the Country Music Hall of Hall of Fame (who created the box and released it in association with Warner Brothers Records) wouldn’t get around to inducting Pride, its first Black member, for another two years. And the Hall was then still seven years away from inducting Grand Ole Opry legend Bailey and nearly a quarter century shy of welcoming 2021 inductee Ray Charles. As Rhiannon Giddens notes in “A Reckoning,” her essay contribution to a new, expanded edition of From Where I Stand, since 1998 we’ve gotten “a bit better at talking about the African American co-creation of country music and absorbing the idea of a creolized culture of the South rather than pockets of white and black that only met in violence.”

From Where I Stand was by no means solely responsible for the more expansive and integrated country canon taking shape, however slowly, in our new century. And it hardly gets all the recognition for the sharper ways race and country music are now talked and written about by many music journalists, critics and academics, and by artists and fans too. The bulk of that credit must go to Black country musicians and writers themselves. There’s no doubt, though, that FWIS helped to jumpstart countless conversations that might not otherwise have taken place. The very idea that there existed a significant Black audience for country radio, and country music generally, was revelatory back then—at least to most white folks.

According to Bill Ivey, the Hall’s director at the time, part of the project’s inspiration came directly from Black country artist Cleve Francis. A founder of the Black Country Music Association and a country singer whose 1992 single “Love Light” is included on FWIS’s Disc 3, Francis made a point to share revealing polling data with the Country Music Foundation: 24% of the Black adult radio audience listened to country. For the box set, that insight was underscored in biographical liner-note essays from two esteemed elders of Black country journalism: “Digging Country’s Roots” by Claudia Perry and “This Is My Country” by Ron Wynn. Perry (who passed away in May) began her essay by contrasting “white” country shows she attended, where she would inevitably be asked several times “what I’m doing here,” with Black country shows in Houston, with “3,000 cowboys and cowgirls… in full western regalia.” Neither Lil Nas X, taking his horse to the old town road, nor Cowboy Carter, atop her white stallion, could tell Perry’s Houston Black country community nothing.

While the original From Where I Stand opened minds and sparked conversations, the new FWIS is understandably less groundbreaking. It will prove essential, even so, for the way it documents where we stand today, and how we got here. That’s thanks especially to FWIS’s all-new, all-21st century fourth disc, titled “Reclaiming the Heritage.” Ditto for that new essay from Giddens and another, “Soul in My Country, Country Down in My Soul,” from singer and “Color Me Country” radio host Rissi Palmer. (The box’s original essays—by Perry and Wynn, plus Bill Ivey and Bill C. Malone, as well as artist bios by John Rumble—are all reprised here and were collectively nominated for a liner notes Grammy in 1999.)

I won’t go through each of the discs in detail. (You can check out complete track listings, liner notes and more here.) But I do want to note key revisions to the new set. Disc One, “The Stringband Era,” is unchanged from the box’s 1998 edition. As I put it back in the day for No Depression, this first disc collects “artifacts of a period when the great pool of shared American song and sound had only just begun to be redlined into marketing niches of ‘hillbilly’ and ‘race’.” (Read my review here.)

The new second and third discs, on the other hand, make some minor but smart revisions. Disc Two, “The Soul Country Years,” still focuses on Black artists doing R&B or soul versions of country-identified songs but has now switched out Al Green’s hypnotic 1972 reading of Kris Kristofferson’s “For the Good Times” for what was the original set’s most glaring omission, Ray Charles’ “I Can’t Stop Loving You.” That was a tough call, I’m sure, but the right one. Charles’ smash cover of Don Gibson’s country classic was so much more than another great record. In “Black Experience in Country Music” terms, it was world historical.

Disc Three, “Forward with Pride,” once again opens with several cuts from Charley Pride himself, then continues with tracks by artists who followed in Pride’s mainstream country footsteps—albeit without anywhere near Pride’s pioneering success, to put it mildly. (I’m guessing this disc was where many younger listeners first encountered Linda Martell, whose “Color Me Father” remains a standout here. Her Color Me Country wouldn’t be reissued until 2014.) This time out, though, there’s one less Pride entry (his exquisite “I’m So Afraid of Losing You Again”) and Fats Domino’s contribution to the disc (“Whiskey Heaven”) is gone too, though as Domino is already represented on Disc 2 (with his version of Hank Williams’ “You Win Again”) that seems fair enough. In far greater need of exposure, Ruby Falls (“Show Me Where”) and “female Charley Pride” Lenora Ross (“Lonely Together”) fill in deservedly.

It’s the addition, though, of the entirely brand-new Disc 4, “Reclaiming the Heritage,” that should steal headlines. The original FWIS was thrilling, in part, because it argued that Black country music and musicians were as old as the genre itself—a once controversial claim that today, finally, thankfully, is the conventional wisdom, or getting there anyway. The new FWIS, and Disc Four particularly, is thrilling because it documents, if incompletely, how Black country music and musicians have asserted themselves in this century. And what a Black country century it’s been!

Cuts including “Ruby, Are You Mad at Your Man?” by Rhiannon Giddens’ former neo-string band the Carolina Chocolate Drops, and “Touch My Heart” by Mavis Staples (the title cut from the Robbie Fulks-produced, 2004 Johnny Paycheck tribute) testify powerfully that earlier Black country styles persist even now. But the thrust of the story here isn’t retro in the least. With 2008’s “Don’t Think I Don’t Think About It,” the first country No.1 by a solo black artist since Charley Pride in 1983, Darius Rucker dragged nineties rock sounds into the country mainstream. Kane Brown, with “Worldwide Beautiful,” and Breland, with “Cross Country,” have done the same with downhome versions of Babyfacey R&B. “Black Like Me,” by pop-country diva Mickey Guyton, is perhaps the modern “Black Experience in Country Music” anthem.

The sheer variety of Black country collected here is impressive: Yola’s Americanapolitan, Cowboy Troy’s heavy-metal hick hop, Blanco Brown’s line-dancing throwdown. I’m particularly glad to see Giddens, Rissi Palmer, Allison Russell, Valerie June, and Miko Marks all spotlighted here. First because they’ve been doing the work for so long, and so well, but also because they point to how the story, and the work, is ongoing. It’s no coincidence that each of these women contributed to one of the essential (and just one of the best) releases out this year—on an album dedicated to yet another groundbreaking Black country elder: My Black Country: The Songs of Alice Randall. (Charles wrote about Randall’s book here; we wrote about some of our favorite tracks from the project here.)

Of course, there’s so much more great modern Black country that could have been included. I say that, in part, because a few the omissions are sore-thumb obvious. Beyonce’s “Daddy Lessons,” the song (in versions with or without the Chicks) most often cited as the key launching pad for what Giddens, in her essay, terms “the Black country renaissance,” is missing here. So is the record that rocketed the renaissance into orbit, Lil Nas X’s “Old Town Road.” Like “I Can’t Stop Loving You” previously, the absence of those records is likely explained perfectly well by an inability to acquire the rights, but that doesn’t make their absence any less glaring. Similarly, not giving a tip of the hat somewhere here to Holly G. and the work of the Black Opry represents a frustrating hole in any “Reclaiming the Heritage” narrative.

On the other hand, those omissions will get covered somewhere along the way. (Charles and I wrote up a few of Beyonce’s Black country forebears here.) It’s worth remembering that the original FWIS’ “Soul Country” disc inspired later collections itself: The Dirty Laundry anthologies from Trikont and the Where Country Meets Soul sets from Kent, for examples, not to mention the dozen or so CD-R’s I assembled and burned for myself. “Reclaiming the Heritage” seems destined to seed more anthologies, more box sets—and personal playlists galore.

The next frontier for recounting the “Black Experience in Country Music,” I think, or one of them anyway, is to conceive of that experience more expansively, more genre fluidly, and to lean into the knowledge that what we call country music has always been a synthetic genre, “creolized,” never pure. The Black country experience certainly includes those moments, as Disc 3 demonstrates, when a Black artist records in a style clearly connected to sounds already identified as country; it also includes, per Discs 1 and 2, the times when Black artists perform songs already closely associated with the genre. But the Black influence on country music has always gone far deeper.

Just a couple of quick examples of what I have in mind. It’s great that Ivory Joe Hunter is represented twice on From Where I Stand with his cover of the Ray Price hit “City Lights” and with a live version of “He’ll Never Love You” cut at the Grand Ole Opry in 1972. But Hunter’s 1950 hit “I Almost Lost My Mind” is far more representative of how white country acts quickly absorbed Black mid-century balladry, and his “Since I Met You Baby” is maybe the greatest proto-Nashville Sound record I can think of. Or take Dobie Gray. His “From Where I Stand” provides the box with its title track, pulled from a country album that he cut in 1986. But Gray’s signature hit, “Drift Away,” was cut in Nashville with Nashville studio musicians and its gentle country rocking style is far more predictive of where country music was headed in the mid-seventies and, for that matter, just about ever since. (I wrote about both Hunter and Gray’s contributions to the Best Country Albums of 1973 here.) Same thing goes for Arthur Alexander, represented here by his great cover of “Detroit City,” but whose most profound and enduring contribution to country are the country-soul hits, like “You Better Move On,” that he cut in Muscle Shoals with white session players who later took that sound to Nashville. Put it another way: If any of the replacement singles I suggest above had been cut originally by a white vocalist, we’d already deem them plenty country enough.

This way of thinking can help us to appreciate that country is a much bigger country than most of us have previously allowed—and that just about every country song, somewhere back there, is at base a Black country song. That’s a bigger discussion than I’ll take on here, obviously, but that’s the place we need to head to, I think. It’ll move us closer to fully appreciating “The Black Experience in Country Music,” helping us better understand the rich complexity of country traditions and their contemporary currents. And it will make for another hell of an essential box set.

If you like what you’re reading here, please think of subscribing to No Fences Review! It’s free for now, although we will be adding a paid tier with exclusive content soon. Also, if you’d like to support our work now, you can hit the blue “Pledge” button on the top-right of your screen to pledge your support now, at either monthly, yearly, or founding-member rates. You’ll be billed when we add the paid option. Thanks!

Enjoyed reading this and especially glad to see the fourth disc, although I agree with you on the omissions. I didn't realize Claudia Perry had died; I worked at the Houston Chronicle for 18 months while she was at the Post and saw her at a few shows. She was always kind and willing to chat. RIP.

I learned so much reading this, thank you! So much to listen to.... Listening to Al Green's 'For The Good Times 'now and can't believe I never heard this gem before. I wrote a bit about the black history of country music a while back too, you might enjoy: https://locarmen.substack.com/p/black-pearls