Dolly Parton and "White Limozeen": a conversation with author Steacy Easton

Charles talks to the author of a new book on artist and album

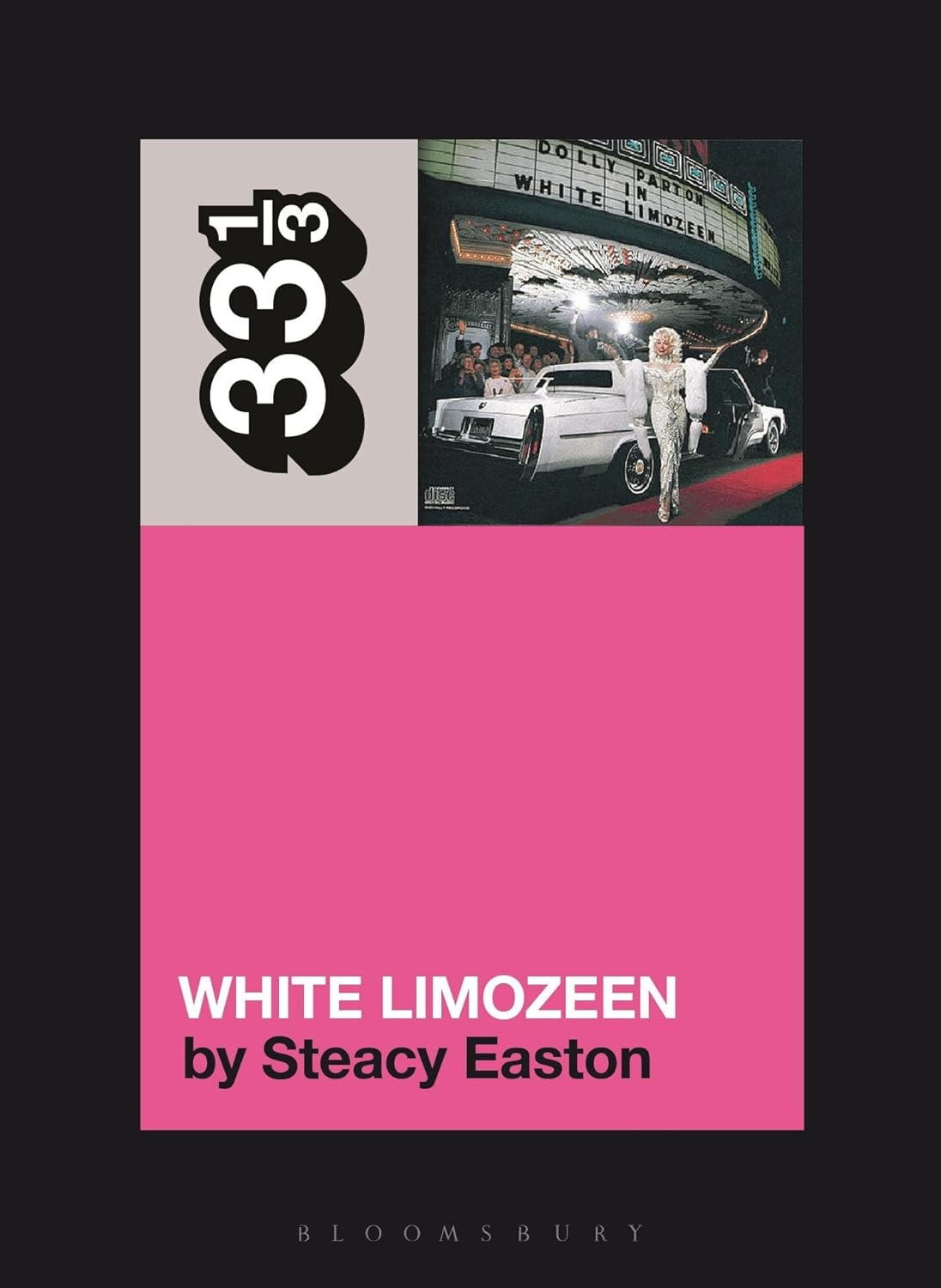

Steacy Easton is one of our favorite country critics and analysts. Their vivid and uniquely insightful writing on country and its contexts - paying particular attention to questions of gender, sexuality, and performance - is like nobody else’s, and they are one of the essential voices in the contemporary conversation. (They’re also an acclaimed memoirist whose Daddy Lessons was released in 2023.) Their newest book, an entry in the venerable 33 1/3 series, takes a deep dive into Dolly Parton’s 1989 album White Limozeen, as well as drawing in a much wider set of contexts and consequences for the album, the artist, and the moment in country music. It was a thrill to talk with them about the book and so much more.

Charles Hughes: Dolly Parton has so many memorable records, both celebrated and under-appreciated. What led you to write about White Limozeen?

Steacy Easton: I think from most cynical to least cynical. The 33 ⅓ series does not really publish books about country music and they tend to publish work that is slightly odd or strange–seemingly less interested in the canon, so it seemed it might fit. There is this term that Jean Cocteau invented, in 1949, un film maudit, or “a cursed film” – a film that was so fucked up that it was a kind of auteur’s failure; and my first thought was wondering if Dolly ever had one of those. There were a couple–the album before this, Rainbow, being less successful, and also the album she made after 9/11 – For God and Country. I did not want to write about the American culture of patriotism after 9/11, and I thought about pitching Rainbow, but the thing about the film maudit is that there has to be something in its failures that is worth retrieving. I don’t really find anything about Rainbow worth writing about. It’s not only a failure of an album aesthetically, it’s a boring album. Those were the most cynical records.

I am really interested in how artists construct personae, how they build up a public showing, and Dolly is really good at that–the making of personae against a person is hard work and its own artistry; in 1989, she was doing really well and then she was crashing and burning. It’s the only time in Dolly’s history where the seams show, where there is an anxiety about not knowing exactly what to do next: she succeeded, then all of a sudden she had a few projects in a row that completely failed. With White Limozeen, you can see how carefully she built herself up again. I admire artists who are cynical, who know how to work an audience, and who fight hard—this was a really good example of that. Also, I think of Dolly as a singles artist, though she has great albums. I knew there were a cluster of Dolly song types–the hillbilly song, the fuck song, the Jesus song, the bucolic arcadia—and this album had all of them. Plus, related to the Jesus song, I really wanted to write about her 1990 Dove Awards performance of “He’s Alive,” and this let me do that.

Sort of related, part of me knows there are a chunk of country albums, mostly made by women, that would be really interesting as 33 1/3rds–but because of the insular nature of Nashville, I don’t know if they will ever be allowed, maybe because they are just not hip. So in a coded part of my head and in early drafts, this proposal let me write about, let’s say, Barbara Mandrell’s Moods, or Connie Smith’s God is Abundant or Skeeter Davis’s It’s Hard to be a Woman or Terri Clark’s Terri Clark, or Tammy Wynette’s Womanhood or Kitty Wells’ After Dark, or pre-Beyoncé Linda Martell–and I bet every country critic has a dozen similar lists.

CH: You’re such a deft critic and analyst of gender and sexuality in country music, and Parton provides such an interesting opportunity to delve into that relationship, both in terms of the sound and the symbolism. What does Dolly Parton teach us about sex and gender in country, especially in the period of her career represented by White Limozeen?

SE: Oh, this is such a difficult question. I think that one of the gifts of Dolly Parton is that she tries really hard not to teach us anything. Sarah Smarsh’s book She Come by It Natural is how much the kind of high femme pink artifice of Dolly is in itself a political act; there are some of us who would like her to say the actual words to articulate a working-class feminism that is less slippery, and less capitalist. But, in the words of Mick Jagger, you can’t always get what you want but sometimes you get what you need. I like how open Parton is about sex—she’s really funny about sex, earlier in her career more than now, one of the things about watching forty years of talk show appearances for this book and for a couple of other things, like her friend Fran Lebowitz, she repeats her jokes. (Or like Whistler to Wilde: you will, Oscar, you will.) I like how complicated her relationship to sex work is, and how readily she is willing to give whores credit for her aesthetics and often her ethics. I love that she doesn’t really spend a lot of time arguing for the relational possibilities of her close friend Judy Ogle.

I once wrote a long essay, that was impossible to place, which traced the phrases/words “vulgar” and “tawdry,” in relationship to Dolly—"vulgar,” which is Latin for the people like St. Jerome who translated the bible into the common tongue; and “tawdry,” from St Audrey’s Day, an English feast day where in the medieval era on June 23, the relics were considered again common, too public, and eventually, something that you bought on St Audrey’s Day was considered badly made or in poor taste. Like her song “Bargain Store,” Dolly is a sanctified commonness, a bawdy/bodily commonness, and I think about the class anxiety of my grandmother, my mother, and how much power there is in saying “fuck it” and just be common.

I think of the cult of “Dylanology,” and of the Beatles, and other male geniuses though, and how little we consider both the writing by Parton, and the construction of her personae, as worthy of that work; mostly, perhaps, because it is common.

Lastly, I think Barry Mazor makes the point about my book and about Stephen Deusner’s book on Garth Brooks that both Brooks and Parton are essentially unknowable. Think about how little we know about her personal life, and think about how much we think we know about Dolly’s personal life, and how much she appears to be confessional, and says not much of anything, see how she battles expectations on those talk shows, and really still how little we actually know…that astonishes me.

Dolly’s slipperiness, her refusal to be didactic, her desire to be all things to all people, her lack of teachable moments, is central to this kind of unknowability, and that is fascinating to me.

CH: Throughout the book, you discuss the crucial and sometimes thorny dynamics between Parton, class, race, and region. This is such a hard thing to unpack, especially with an artist as significant and slippery as Dolly Parton – how did you approach it, and what did you learn?

SE: Maybe it’s my iconoclastic tendency, but there were first drafts of this, which were much angrier; a real instinct to talk about how there was no “there” there—which is absurd, the albums are so great. There is also a queer/trans reading in country music, where you get so hungry for actual content that you (me) as a critic might not see what is actually here. So, I wrote the angry version, and then I wrote a soft version, and then I let the material show me a middle ground. Dolly knows what she’s doing, she knows how to run a narrative, so working at an oblique angle to that narrative (see for example how she greases up the SNL performance of “White Limozeen,” or about how she made a lot of money on real estate with the Whitney Houston money, and how after the death of George Floyd and the rise of Black Lives Matter, she talks about that money like it’s an act of financial justice, but the real estate she bought was largely Black and now it’s not.

In my method, there has to be some biography, but there is also separation between artist and art, that great art can be made by people who have politics that are not yours. I think that we reserve this for like the novels of Heidegger or the novelist Céline or other white dudes, and we want Dolly to be good – and she’s a capitalist, she’s anxious about capital, she’s anxious about paying her rent. Especially on White Limozeen, where paying her rent (and other people’s rent–she had to pay a band, and a manager, and the whole little industry that surrounds her) was a real concern. I get some of this from some Marxist historians of the 1970s – people like Christopher Hill or Dorothy Thompson – who paid very close attention to workers on actual land and factories, I tried to do that a little bit, thinking about both the parts of women’s work, in country music, but also what it meant for Dolly as a boss.

I also wanted to note Joseph Thompson, in his book on the US and the military, in regards to county music. He read a bit of this and did some necessary corrections about my attitude concerning Appalachia, which I am grateful for. One of the things about Thompson’s book was that it could have been either a continuing of American propaganda, or it could have been a standard leftist paranoid style renunciation of it – but there were such difficult questions, so well considered, about what soldiers actually listened to, and how they were influenced in their listening. Thompson’s interest in what actually happened on the ground, and his belief that we can learn about that, that the archive has answers, and answers that might not be the ones we want–were really germane to my own methods.

I secretly want to be a historian, but I worry I am too much of a magpie for that – not careful enough and not patient enough. But there were some archival attempts here that really followed other historians' leads. (Yours too, Charles.)

CH: So much of Parton’s story is discussed in terms of musical “crossover,” especially between country and the shifting pop world. (It’s how I’ve written about her, for example, in ways that I wish I’d have had your book to help me make stronger.) What’s at stake when we talk about “crossover,” do you think, and how can we do it in a way that both honors a singular artist like Parton and puts her in the proper contexts?

SE: I love Dolly’s quote about this, found in Mitchell Morris’ brilliant book The Persistence of Sentiment: Display and Feeling in Popular Music of the 1970s. He quotes the 1997 interview that she did with Country Weekly:

Before I crossed over, when I was being so totally true to country music, I wasn’t making a dime. I couldn’t even buy panty hose hardly… People thought I was just rolling in dough because I was having these chart records. Number One records, “Coat of Many Colors”, “I Will Always Love You”, and “Jolene.” You know what? “I Will Always Love You” sold 100 000 copies, and “Jolene” sold 60, 000 copies. “Coat of Many Colors” didn’t even sell that… So I thought I’m going to broaden my appeal. I’m going to have to cross over—try to get into bigger television, stuff like that. I made that choice…and I got crucified…at the time. People thought I’d made a major mistake. But if I hadn't done that, I wouldn’t have any money now…” (182)

I think that one of the things we really under-consider about Nashville is how in the 1970s it was relatively small potatoes because of sales: The infrastructure was not there in ways we think they were, and it was built in the Urban Cowboy era and the Garth era. One of the things that I thought about in this book, and in that quote, and in the crossing over is that Dolly is ambitious in ways she could be considered greedy, but she was also essentially anxious. We don’t spend a lot of time talking about money in our culture, and we think people have made it when they haven’t necessarily. So, Dolly crossed over because she was worried about making rent–for her, for her family, for the people who worked for her.

There is an element of flop sweat to White Limozeen: The hard work was evident, and the anxiety was evident, and there is this counterfactual moment – what if White Limozeen fucked up, what if it didn’t land? There is so much chaos to these decisions, and there are a few times where it strikes me that someone through pure force of will turn the ship around. I think we have to be really careful not to make that systematic, but it’s fascinating to me to think about what that means in terms of Dolly. You cannot help but be a little inspired that the idea of hard work, of that bullshit “American Dream” which fucks more than it rewards, may have actually done something. But the something that it did was because Dolly made a series of decisions which rested on questions of how do I make the most money, in the least amount of time. Artists aren’t supposed to think like that, and god knows I don’t think like that, but it’s nice when the dice rolls sevens and elevens, for working-class women of certain geographies. It’d be nicer if we didn’t have to roll those dice.

CH: You’ve written books about Tammy Wynette and Dolly Parton, two of the iconic women of country music, and you’ve challenged us to think both beyond and within the standard narratives about each of them. I’m not trying to put them up either as comparable or opposed, but I’m wondering how you think about them together now that you’ve done such crucial work on their respective lives and bodies of work.

SE: I think that Tammy didn’t have the control of Dolly. Dolly’s control is under-considered, and her will is under-considered. They both crafted a kind of personae, and the split between personae and personhood was key. Tammy tried really hard to make that happen, but the mess of her life always came to the forefront. Tammy also had the anxiety of all of it going away, and it did for her, that she had no double or triple backup plan. Dolly had the movies and the television shows and the Hollywood production gigs and the theme park. I think that Dolly recorded more and was more curious about the edges of production – she produced more interesting records. I think there was also a tenderness to each of them, a good humour. There is that story of Dolly doing Tammy’s makeup and hair when Tammy was in the hospital room – that story, about creation of self, and mutual aid of a sort, is one that I find incredibly telling and profoundly moving. I never felt sorry for Dolly, and I left writing the Tammy book feeling deeply sorry for her and the shittiness of her choices.

I also think that Dolly had luck with Carl Dean—that he didn’t want to be part of the machine, that he was quiet, that they’ve lasted as long as they have, that he was solid and disappeared. We know nothing about their marriage, but Tammy’s husbands depended on her for career and financial success – and, with the case of George Jones, artistic success. Dolly might have depended on Carl for a lot of things, but she made sure that dependency wasn’t public. The gap of Dolly as a domestic figure is a notable difference. (Dolly didn’t have children because she couldn’t, but her not having children I think was helpful for her career. The fact that Tammy and Loretta had to raise children in the middle of their successes might also express how the control and the capital worked differently for both of them. I am really curious about this kind of domesticity, because it is so alien to me.)

I also knew Tammy’s (and by extension Loretta’s) politics–Tammy and Loretta were attached to a white political southern-ness, a kind of Lee Atwater moment that made me disappointed in them, which is absurd and parasocial, and which a critic should know better than to fall into. Dolly refusing to state exactly what she thought, and her ability to be all things to all people, to not restrict her sales was key to this.

CH: I had a great conversation with Dr. Tressie McMillan Cottom a while back about the “daughters of Dolly,” as part of her brilliant consideration of Parton that you talk about in the book. What contemporary artists – of any gender – remind you of Parton, and in what ways?

SE: I don’t think there is one. I think that Dolly is sui generis. I think the industry has changed in such a way, that the structure of small markets to larger regional markets to Nashville to the world has shifted beyond recognition—maybe TikTok or Instagram has made that a little different, but I am also not sure if someone has had a lifetime career out of TikTok. Maybe too soon to tell. Carrie Underwood on American Idol in 2005 had some of that machine sheen, and Scotty McCreery too, but not the same capacity. I think there was also, in some times in Nashville’s history, a willingness to let more than one woman on the charts at the same time—see the dozen or so women in the countrypolitan era who charted, or the success of women post Garth, but it seems like we have kind of given up on that. The Americana place which Dolly landed around the Little Sparrow era is now its own ecosystem, with some commercial success but not the cultural ubiquity.

The obvious answer would be Taylor; and Taylor did the crossover better than anyone else, but I figure that crossover has some institutional memory, and I don’t know how much she has, the donations to the Country Music Hall of Fame aside. The other thing about Taylor, though, is that she has that tension between public and private personae and does it better than Dolly does. But Taylor has this kind of post-capital, blank childhood. She has the ambition, but she seems crafted entirely for capital: The Eras Tour may be like Dollywood as travelling carnival. She also is crafty about autobiography as a way of teasing the audience, in ways that seem less relational than Dolly.

The interesting thing is that I don’t think there is a cluster of people who try to sing like Dolly or consider themselves like Dolly… which is fascinating.

(There are obviously no black artists who are in this conversation. We all know why that is.)

CH: What’s your favorite song on White Limozeen, and why? What’s your favorite Dolly Parton song in general, and why?

SE: I love how angry “Why’d You Come in Here Lookin’ Like That?” is: horny and angry and funny and willing to forgive a man for fucking around. Also, how it comes pretty close to disco. I really love the title track, but I love the live version on SNL more—there’s a version at the Country Music Hall of Fame, which adds a riotous last verse, including throwing chicken out the sunroof of a vehicle, which is all-time. (Speaking of Dylan, again, we have endless versions of “basement tapes,” live versions, and assorted ephemeral copies. We don’t seem to have that with Dolly.)

I really love her version of “He’s Alive,” but the version she did on the Dove Awards, with its complicated history of Pentecostal singing and racial politics, strapped into a vulgar southern remake of a Busby Berkley production number, is better. Dolly as master of the fuck anthem is under-considered, and the erotic power of her presentation often elides the actual text. When she sings about how she wants to fuck, you absolutely believe her, and the Charlie Rich lushness of “Wait Until I Get You Home,” with Mac Davis, has a rapaciousness which amuses and arouses in equal measure. I also love how melancholy and small “The Moon, the Stars and Me” is with the plucked banjo and piano refrain.

Okay, so best Dolly songs—this was a really hard moment, because there was such a richness of them until about 2000, and then such a paucity after. The Dolly songs after 2000 –“Travelling Thru,” “Southern Accents,” “Seven Bridges Road” — she spent a lot of time with duets, burnishing her legacy, but they never quite hit it for me. It’s fascinating that she seems to have slid through her personae and had that be enough.

Before 2000, I don’t like “I Will Always Love You,” a song that I find saccharine, and over-sung, especially in some of the remastering. But I love almost all of her great crossover hits “Jolene,” “9-5,” “Dumb Blonde,” “Islands in the Stream,” “Coat of Many Colors.”

I love the abject dead child songs, especially but not limited to “Down from Dover,” “Me and Little Andy,” and “Applejack.”

There are so many others. I love the horny disco ones: “Two Doors Down,” “Potential New Boyfriend,” “Why’d Come in Here Lookin’ Like That?”, even “Romeo”…

The harmony work she did with Loretta and Tammy, plus the harmony work she did with Emmylou and Linda…

Bargain Store was the first cassette I ever bought, at a discount store called Biway, and I love the title track. The title has complicated and deepened from there.

Also, “Alabama Sundown,” “Light of the Clear Blue Morning,” “Travellin’ Man” (the 1975 version), “Do I Ever Cross Your Mind?”

Also also: the live version of “Mule Skinner Blues” that she did on Porter Wagoner’s show; the singing she did for Tammy Wynette’s funeral, the SNL performance of “White Limozeen,” the 1990 Dove Awards performance of “He’s Alive,” the performance of “Wabash Cannonball” in Sevierville in 1970, some live versions of “Rocky Top” in the last few years, “9 to 5” at the Oscars… There have been a few Dolly live albums, but she really needs a Basement Tapes.

CH: What’s something you’ve read recently – music-related or otherwise – that’s really exciting you or speaking to you in some way?

SE: Joseph Thompson’s book, as I wrote about earlier, Cold War Country; Francesca Royster on Black Country, Stephen Deusner’s Garth book, any reportage Marissa Moss does. My friend Ben Robinson’s 2024 book of poems, As Is, which is about Hamilton, Ontario, but made me reconsider how we write about place as settlers, and about the ongoing problem of kinship networks. Ann Powers book on Joni, Traveling, which I read in the depths of editing Dolly and made me seriously wonder what it meant to be an audience. Zane Koss has a new book of poems called Country Music out next year, and what I have heard just kills me. Niko Stratis has a memoir and listening diary out of University of Texas Press next year, and it’s really special, especially for its careful notes of the working-class west. Mercedes Eng. So much of the work in the Racket, the Minneapolis local.

Substacks: Michelangelo Matos, TA Inskeep, Carl Wilson, Marissa Moss and Natalie Weiner, this one, the Metis poet Chris La Tray, Brandon Taylor.

If you like what you’re reading here, please think of subscribing to No Fences Review! It’s free for now, although we will be adding a paid tier with exclusive content soon. Also, if you’d like to support our work now, you can hit the blue “Pledge” button on the top-right of your screen to pledge your support now, at either monthly, yearly, or founding-member rates. You’ll be billed when we add the paid option. Thanks!