Country Style! Tommy "It's All in the Game" Edwards Edition

David looks at one of the earliest albums of country songs ever released by a black artist

[“Country Style!” is an occasional series devoted to a subgenre of album I’ve been obsessed with for years—when a presumably “non-country” artist records an album full of country standards and then, often as not, titles it something like So and So Visits the Country! Or …Sings Golden Country Hits or …Sings Country Style! Please think of these entries more as notes for further study than definitive statements.]

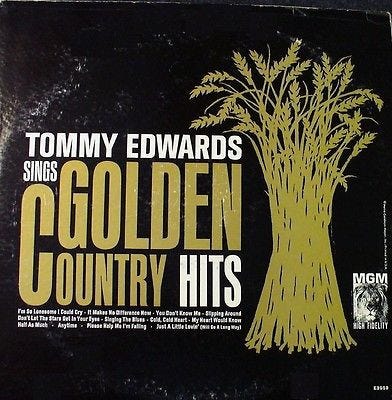

Tommy Edwards - Tommy Edwards Sings Golden Country Hits, 1961

Ray Charles’ Modern Sounds in Country and Western Music was an absolute juggernaut, commercially speaking, sitting at No. 1 on Billboard’s “Top LPs” chart for three and a half months in 1962. It proved a ridiculously consequential album, as well—particularly for the country music industry which drafted on Charles’ success to tweak its sound and expand its audience even as country radio stations refused to spin “I Can’t Stop Loving You” or any of the album’s other singles.

Because the album was famously such a game-changer, I must admit I just assumed for a long time, albeit without really thinking about it too much, that Modern Sounds must surely have been the first full-length album of country songs by a Black artist, ever. (I’m guessing I wasn’t alone?) But, as I’ve strove this century to become more intentional in seeing the role that Black artists and Black sounds have played in the country music story, I learned that Charles was not the first.

As far as I can tell, there were at least two LPs of country songs, strictly defined, by Black artists released before Charles released Modern Sounds in April 1962. The first was San Antonio Rose by the Mills Brothers, released on Dot Records on February 17, 1961. The second, Tommy Edwards Sings Golden Country Hits on MGM Records, was out in stores early in October that same year. There’s so much to say about the Mills Brothers’ influence upon, and their engagement with, country music, and I hope to devote some future essay to the group’s legacy. Today, though, let’s take a quick look at Tommy Edwards, his contribution to the subgenre I call “Country Style!” and his role as a Black country trendsetter.

Tommy Edwards (Thomas Jefferson Edwards officially, after his dad) was born in Henrico County, Viriginia, in 1922. He bounced around the fringes of the music scene there for years, but didn’t get his first break until, at 24, he wrote a song, “That Chick’s Too Young Too Fry,” that found its way to R&B star Louis Jordan who scored a No. 3 “Race Records” chart hit with it in 1946. For a time, he also fronted a little combo called the Tommy Edwards Trio.

Edwards eventually signed with MGM where, starting in 1951, he had a couple of dozen solo singles. All of these were in an agreeable, if indistinct Nat “King” Cole-style. More like Cole-lite actually, as they were missing King’s jazzy piano juice and as Edwards’ vocals were airier, thinner, more precisely enunciated than Cole’s warm tones and sandpapery texture. None of these early sides were particularly big radio hits—with one exception: A dreamy love ballad Tommy wrote himself, “All Over Again” was adorned with French horns, fluttery strings and flute fills that nearly swamped their singer’s whispery baritone but became a Top Ten R&B hit, albeit an extremely mainstream-pop sounding one. Edwards’ follow-up singles were all significantly less successful. But it’s telling that, in a moment when stars like Tony Bennett, Dinah Washington, Jo Stafford and many others were scoring hits with string-swollen versions of songs by Hank Williams, Edwards cut a couple of those himself. He had a middling hit, for example, with a version of “You Win Again” in 1952. Subsequent sides, including a 1953 mainstream pop take on Williams’ “Take These Chains from My Heart,” didn’t chart at all.

Then in 1958, as MGM was preparing to drop Edwards, his longtime producer and arranger Leroy Holmes suggested they revisit the song that had been the B-side to “All Over Again,” another swoony ballad called “It’s All in the Game.” (For more on the crazy origin story behind Edwards’ signature hit, check out Carl Wilson’s 2018 Billboard piece, “A Trailblazer’s Twisting Path.”)

This new version of “It’s All in the Game” added backing vocals that sounded more doo-wop-meets-the-Jordanaires-plus-the-Anita-Kerr-Singers than they did Hollywood soundtrack choir. Even more importantly, the new recording was driven by a restrained but prominent drummer and Edwards vocals felt looser, warmer, even a little twangy. In other words, Edwards and Holmes’ reimagining of the number was geared to pop’s new mainstream—post-rock and roll, leaning Nashville Sound—and it was an international smash. Edwards’ “It’s All in the Game” spent six weeks at No. 1 in the US, three in the UK, and became among the defining romantic ballads of the 20th century. Tender and patient and forgiving, and maybe just a little cynical, “It’s All in the Game” is pop perfection:

“It’s All in the Game” has also had a bit of an afterlife as, if not a country standard exactly, then at least a song always game for taking a day trip out to the country. “It’s All in the Game” has been covered through the years many times by country singers, including Johnny Bush and Bobby Bare, Slim Whitman and Freddy Fender, Narvel Felts and Tennessee Ernie Ford and Wynn Stewart, among them. Tom T. Hall had a No. 13 country hit with the song in 1977. Merle Haggard had a minor hit with his own version of the song in 1983. (Spoiler alert: It is lovely.)

For his part, Edwards seems to have sensed his signature song and the country numbers he’d been cutting all along would play well with one another. Edwards’ debut LP, It’s All in the Game, included his re-recordings of Hank Williams’ “You Win Again” and the Hank Snow hit “(Now and Then There’s) A Fool Such as I” (Edwards had first cut that one back in ‘53) and was filled out with country-enough numbers like “That’s All” and “The Morning Side of the Mountain.” Later that year, he released a 7” EP that followed the same genre-fluid pattern, including his versions of both the country classic “I Really Don’t Want to Know” and the close-enough “Don’t Fence Me In.”

Soon, he was going all in on the country stuff. In 1961, half a year after the Mills Brothers’ San Antonio Rose, and half a year before the appearance of Brother Ray’s world-historical Modern Sounds, Edwards released Tommy Edwards Sings Golden Country Hits. It’s unclear exactly what prompted the project. His label MGM, AKA Hank Williams’ old home, certainly seemed to be leaning in that direction itself at the time: A full-page MGM ad in Cashbox that fall featured Tommy’s album and another “Country Style!” set from pop singer Jay P. Morgan called That Country Sound as well as related titles like The Conway Twitty Touch and Folks Songs by Joni James. I wonder if Edwards (and MGM, for that matter) considered how groundbreaking and potentially controversial it was for a black man to cut an album’s worth of country classics just a few months after the Freedom Rides and only a year after the Nashville Sit-Ins. I wonder if that was maybe part of why Edwards did it.

What seems plain to me is that Tommy Edwards Sings Golden Country Hits was likely one part of the equation prompting Ray Charles to cut a country-song concept album of his own early the next year. Charles, who’d already had a hit single with his rousing version of Snow’s “I’m Movin’ On” in 1959, hardly needed Edwards to introduce him to the genre. But as a country fan for most of his life, Charles surely made note of Edwards’ new album when it came out that fall. Golden Country Hits had been out a couple months when Charles unexpectedly informed his producer Sid Feller (around Christmas of 1961, according to Charles biographer Michael Lydon) about plans for a country album. Edwards’ and Charles’ albums also share four titles: “You Don’t Know Me,” “My Heart Would Know,” “Just a Little Lovin’,” and “It Makes No Difference Now.” (Easy to imagine Charles also made note of the Mills Brothers’ country album that year too, of course, though that effort leaned hard into the singing cowboy side of the genre and includes none of the songs chosen by either Edwards or Charles, who both take a more “golden country hits” route.)

Of course, Edwards’ and Charles’ finished products sound completely different from one another. A few years on from It’s All in the Game, Edwards and Holmes’ country song arrangements have even more rhythmic drive than before, though more in the way of cha-cha-cha or other tame exotica than rock’n’roll’s big beat, and some staid electric guitar has been added as well. Otherwise, Golden Country Hits sounds pretty much like It’s All in the Game, at once both updated and already dated. Next to the big-pop and country-soul Charles would soon create for his Modern Sounds in Country and Western Music, Edwards’ album comes off more like Old-Fashioned Sounds in Country and Pop.

To compare Tommy to “The Genius” isn’t really fair, though, and sets us up to miss the charms of Edwards’ trailblazing effort and undersells the significance of this little-remembered black vocalist getting the idea first. Edwards’ readings of “You Don’t Know Me” and “Slipping Around” are knowing and playful and the arrangements, which resist toe-tapping but make the singer’s confessions sparkle like tears that never quite fall, are not like any others you’ve ever heard—no matter how well you think you know those songs. My favorite cut here is the single, released a month or so ahead of the album, “I’m So Lonesome I Could Cry.” Edwards doesn’t sing it lonesome at all. More like he’s crying tears of joy to finally be freed of lonesome thoughts all together. Falling stars streak thrillingly across the purple sky, the night’s never felt so long. Tommy sounds like he hopes it never ends.

Edwards died in 1969, just 47, possibly of a brain aneurism, possibly of cirrhosis of the liver. He didn’t get any obits in the New York Times or even the music industry trades, and if he’s remembered at all these days, it’s for his amazing “It’s All in the Game.” His Tommy Edwards Sings Golden Country Hits, meanwhile, has never been reissued (though you can stream it here) and remains all but unknown. I wish more people knew it and the rest of his country-song catalog. Tommy Edwards was a Black country music pioneer.

Want more “Country Style!”? Check out the “Steve & Eydie Edition” and the “Duane Eddy Edition” in the series.

If you like what you’re reading here, please think of subscribing to No Fences Review! It’s free for now, although we will be adding a paid tier with exclusive content soon. Also, if you’d like to support our work now, you can hit the blue “Pledge” button on the top-right of your screen to pledge your support now, at either monthly, yearly, or founding-member rates. You’ll be billed when we add the paid option. Thanks!

"It's All in the Game" has always been a masterpiece to these ears. I've never found the time to dig deeper into Tommy Edwards until now. Thanks for the tip and, as always, for the compelling read!

Unfortunately this isn't on Spotify :(

I love Merle's version too!