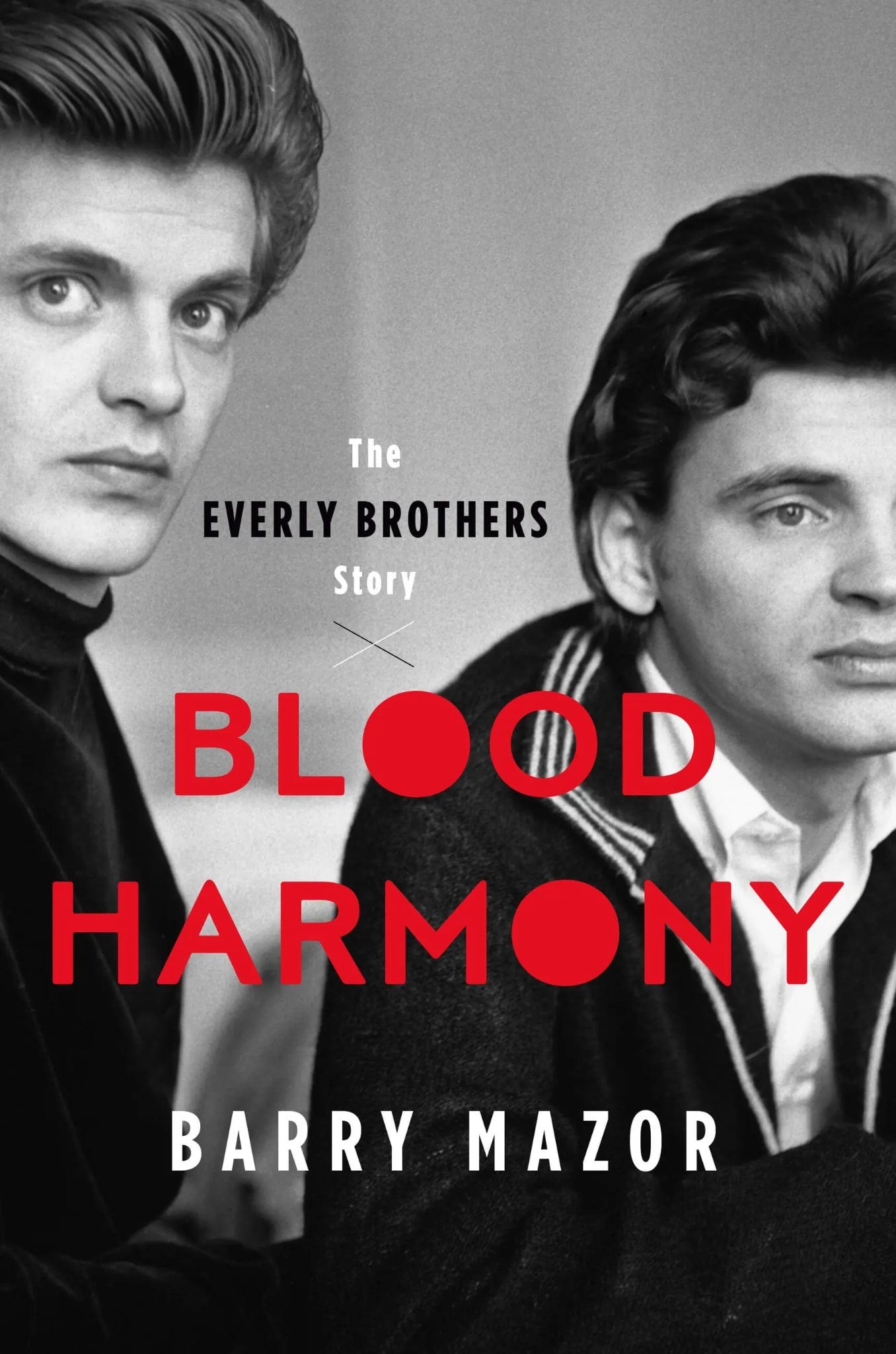

Blood Harmony: A Conversation with Barry Mazor

David talks to the author of a new biography of The Everly Brothers

Barry Mazor is one of our favorite music writers here at No Fences Review, so we’re beyond pleased he was able to answer a few questions for us about his career and, especially, about his latest book, Blood Harmony: The Everly Brothers Story.

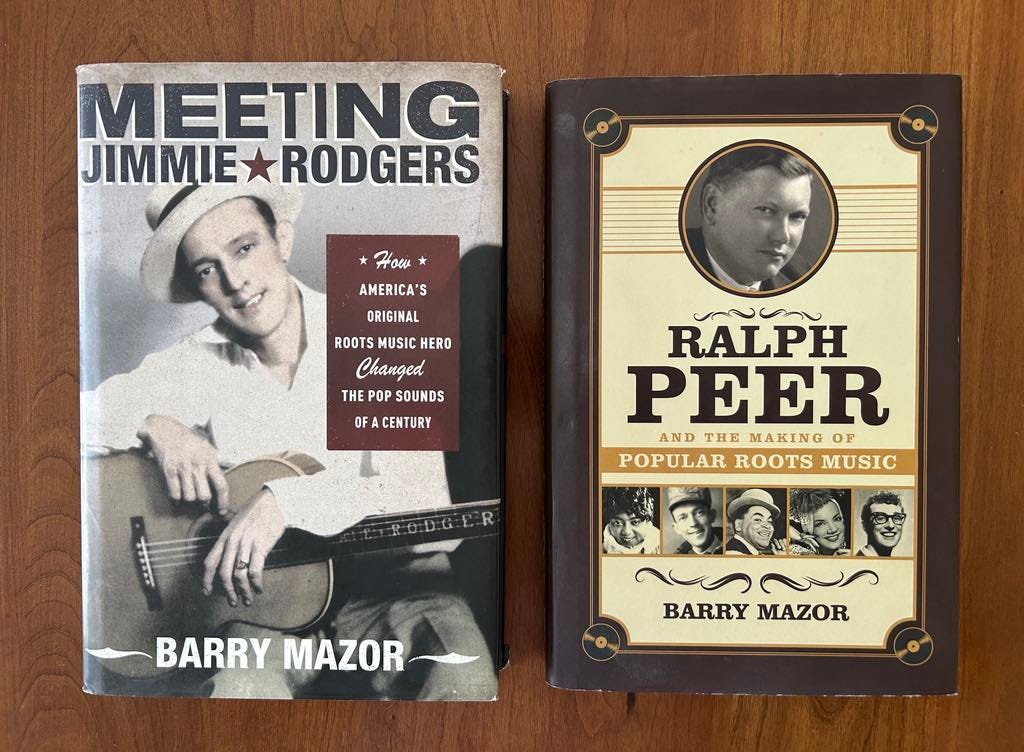

I first met Barry back in the mid-1990s on the “Postcard2” listserv, an online fans-and-critics community devoted to that moment’s emerging alternative country scene; we’ve been great friends ever since. (He wrote about the not quite legendary “P2,” as it was more often called, in a 2015 essay.) Barry had written for both Crawdaddy and NYC’s SoHo Weekly in the 1970s, but the alt.country scare of those years helped prompt for him what became a full-time career as a music journalist. He was a senior editor at No Depression magazine for much of its original print run, has been a regular contributor to The Wall Street Journal since 2003, and has now authored several books, including: Ralph Peer and the Making of Popular Music (2016); two volumes on the recordings of country singer Connie Smith for Bear Family Records; and a book I’d put on the country-music-book short list, Meeting Jimmie Rodgers: How America’s Original Roots Music Hero Changed the Pop Sounds of a Century (2009). His Everly Brothers biography, Blood Harmony, is out July 22.

David Cantwell: First off, Barry, what led you to the Everlys as a subject? What was your history with them and what led you to think, “Wow, that’s not just a good idea for a book; it’s a book particularly well suited for me to write?”

Barry Mazor: The immediate starting point was an online conversation with author-singer Elijah Wald, over three years ago, who was asking a question so many of us who do serious research and writing on American music had been asking: Why wasn't there a deep biography to turn to on the Everlys, the only original inductees in the Rock & Roll Hall of Fame without one—or more. My very astute literary agent, Paul Bresnick, caught this back and forth and asked, on the side, "Then why don't you write one?" And my very fast answer was, "Why don't I?"

But that response came so automatically because I'd been listening to them and loving so much of what they did at every stage of their long career, starting with their "Bird Dog" on a transistor radio, when I was eight. The sort of music they made, riding and crossing the lines between various flavors of roots music and pop, is what's always especially grabbed my attention, as an audience member, and then as a writer. How people work the push-and-pull between pop's need to “make it new" and roots music's to "keep it in conversation with history and place" often makes for some drama—a good story. And Phil and Don saw a lot of push and pull.

One other thing: I grew up amidst a good many performers--actors, dancers, musicians, and though I'm none of those myself, I think it gave me a certain feel for the way they think and respond and what they want. At least, some have suggested as much to me!

DC: Would you talk a little about your research process, Barry, and your writing process too?

BM: What I meant to do, foremost, was get at who these brothers really were, what they were doing and thinking and feeling in any given time and place—to keep them on the page. This story is history now. It will startle some people to hear, but the first time the Everlys recorded a single was seventy years ago this November. Not a single person directly involved in the making of their big breakthrough hits on Cadence records—“Bye Bye Love," "Wake Up Little Susie" and "All I Have To Do Is Dream," etcetera--is alive today. So this mostly demanded research into what's been documented.

I always start with a timeline, with obvious, readily available material. For Blood Harmony, that meant pieces in rock and country encyclopedias, discographies, and in the fan-written books about them done 30-40 years ago. Then there was a solid year-plus of fleshing up those timelines, from national publications from the day, local and international paper and magazine reports archived and now more available online. and with some terrific help from the Everly Brothers International fan club. They'd kept the clipping books pieced together by dedicated Everlys fans all through the years, and they made all that available to me. Lined up, that material started bringing up themes I had to explore, questions I needed to try to answer. I hadn’t begun with a lot of preconceptions about Don and Phil's relationship or how they came to make the specific music they did, but putting the events in order, down to sometimes an hour-to-hour basis, revealed things about the experiences they faced.

An example: After a stint in the Marines and some dramatic personal events, including attempted suicide by Don, things seem to have calmed down and hits were still happening, if less often, as the calendar is flipping to 1963. Then the day before Phil finally gets married to long-time beau Jackie Ertel, the Beatles' "Please Please Me” is released in England—marking a new, less simple era in the Everlys' career. The Fifties they're so associated with are over.

About the interviews done for the book: A good many involved who are still around have been telling or embroidering the same stories for decades; they're in print and quotable, from back when. I mainly chose to speak with friends and co-workers who'd not been tapped before, which I think readers will find revealing.

DC: The Everly Brothers are on that still short list of acts inducted into both the Rock & Roll and Country Music Halls of Fame. One of the things your book is particularly good at, I think, is tracking how their understanding of themselves in relation to those genres was a kind of moving target across their career. Would you talk just a little about their relationships to country and to rock? I mean, particularly in terms of how they saw themselves.

BM: They certainly made a long-lasting contribution in bringing such country-derived harmony singing into rock and pop—played off against Don's thrashing R&B-influenced guitar slamming—the opposite of more typical R&B vocalizing/country picking in rockabilly. And the Beatles would be happy to tell us so.

How they described their own synthesis, and how they worked it, changed all through their 60-some years as performers. (No doubt influenced partly by who they were describing it to.) Their musical Daddy Ike, in truth, had made sure that, still kids in the '40s, they were as familiar with harmonious black pop groups like the Ink Spots as with hard country boogie acts like the Delmore Brothers. In Iowa, the format of the family’s radio show, aimed at early morning rural risers, needed to veer country and so, then, did Don and Phil.

But as the influence of R&B on them took hold and grew in the '50s, and the hits came, they tended to say they were "country" or were playing "beat music" about as often. When adult-oriented country radio dropped them for singing about teenage experiences too much, they were "rock and roll," though never exactly "rockabilly" in their own mind, and the record labels didn't mind pointing out their ease with old country songs to the folk revival. Off the charts, playing nightclubs, they'd say they were "entertainers." In the late Sixties, when they'd come back helping spur and certainly fitting in with "country rock," they'd say they had always been that, if you thought about it! Solo in the Seventies, Don would tell anyone who'd listen he was a mainstream country singer and always had meant to be—and when they had the mid-80s "Wings of a Nightingale" second comeback, they were on both pop and country charts again, because at that point the roots pop they were making had a home in both places.

DC: Did you discover any new-to-you Everly Brothers recordings or TV performances that you’d point people towards? Also, your book makes a low-key case for the Everlys as being pretty swell album artists, in addition to the great singles act everyone acknowledges. For readers who know the hits but who’ve never dived much beyond those in their catalog(s), is there an album you’d recommend as one to check out?

BM: Well, telegenic as they were, the TV footage is exhaustive, from every stage of their careers. I'd suggest people check out their 1964 Shindig performance of "Gone Gone Gone" for a terrific rocking example. The quiet ballad duos are endless!

On their recordings: It was a revelation to me, and think it will be for many others, how many quality songs on the dark side of things they recorded over the years, definitely not "Wake Up Little Susie" material. Example tracks, easily found now: "Even If I Hold It in My Hand," "The Drop Out," "The Collector," "Nancy's Minuet," "Man with Money," and particularly "Lay It Down," a potent artifact of their predicament and hurt as tensions between them festered. On albums: I think people are aware of the lasting importance of Roots, from 1969, but for those who want to dig in, check out Sing Great Country Hits and Beat 'N Soul from 1965, and Born Yesterday from 1985.

DC: Blood Harmony is a biography so there is necessarily plenty of time devoted to the brothers’ lives off stage, including sibling tensions and marital struggles, as well as the role in their lives of their mother—I believe the technical term for her is “a piece of work.” Along these lines, I was particularly impressed with the way you handled Don’s mental health troubles and suicide attempts—that’s a tough episode but you write about it so straightforwardly, eschewing the merely titillating entirely and taking up not even two full pages of the text. That said, you spend most of your time dealing with the Everlys as artist/entertainers and with the music they made together and apart. How did you negotiate that tension, Barry, between the biographical details and the songs, recordings and performances that are the only reasons anyone would ever care about those biographical details in the first place?

BM: I relate details of their personal lives, dramatic and mundane alike, to the extent that those affected their music and careers—and they did, of course. The truly tight connections between who they really were, how they related, and what music they made emerged for me in the course of writing the book. That's the crux of it. How to get at that? With my screenwriting/film school background, I'm trained to home in on the revealing scenes that add up to the story arc, and I've generally applied that to my narrative writing in general. It seemed to apply here well.

I don't hit readers over the head with it, but during their adult lives, long-term clashing temperaments and over-exposure to each other aside, when tempers really flared between them, it's when lead singer Don was improvising in a challenging way that Phil, for all his skill at it, can't possibly lock onto. Fistfights would happen. And that ten-year break up. Phil told several people late in life, "harmony singing is the purest form of love on earth." So, busting their "blood harmony" had to have felt like a personal, not just a musical, betrayal—even though each, understandably, would sometimes resent having their individual identities lost to being "half" of something. Brotherhood and duet singing can be complicated!

DC: At one point in the book, Barry, you refer to Phil and Don as being part of this or that moment’s “roots-pop convergence.” That phrase reminded me of “rootedness,” a term you used in your book on Jimmie Rodgers, who himself was maybe the OG roots-pop convergence guy? Put those works alongside your Ralph Peer biography, as well as next to long-form features you’ve written through the years on artists such as Little Miss Cornshucks, Gene Austin, Mac Wiseman and so on… It struck me that roots musicians who’re able to converge with pop while remaining deeply rooted is the great topic of your writing career.

BM: Heh; convergence or collision, it's certainly the topic that keeps on intriguing me, as does the culture's and music business's habitual insistence that performers be summed up on a very small bumper sticker. That doesn't work very well for interesting artists—and there's usually a story in that tension, too. Nevertheless, some talents can work the convergence magic. Phil Everly's comment when I interviewed him for Meeting Jimmie Rodgers was among the more quoted ones from that book, and it seems on point: “It's a shame, in a way,” Phil said, “that people think of Jimmie Rodgers as the root of just one thing, when he was the root for so many things.”

DC: Barry, we like to end these author convos by asking you to name a work you’ve read recently, or heard or viewed– music-related or otherwise – that’s really exciting you or speaking to you in some way?

BM: I don't think it will surprise you that the musical-convergence horror film Sinners struck me strongly; don't want to nitpick that at all. And Joseph M. Thompson's book Cold War Country, on the very fresh topic of the relation between the country music business and the military, has some careful, insightful history I'd recommend.

If you like what you’re reading here, please think of subscribing to No Fences Review! It’s free for now, although we will be adding a paid tier with exclusive content soon. Also, if you’d like to support our work now, you can hit the blue “Pledge” button on the top-right of your screen to pledge your support now, at either monthly, yearly, or founding-member rates. You’ll be billed when we add the paid option. Thanks!

This will be something I buy week of release - and I very rarely ever do that.

I’m excited to read this book! My mom loved The Everly Brothers to the point that I say they taught me harmony singing. Great interview!