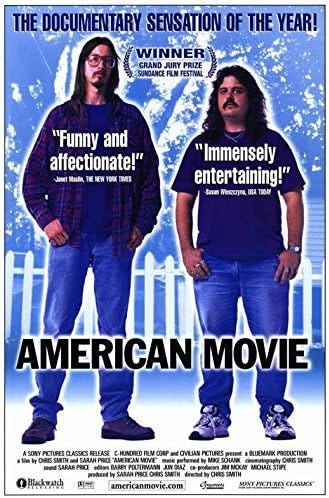

In the quarter-century that’s passed since the oft-heralded “best movie year” of 1999, one film has remained closest to my heart. The documentary American Movie chronicles Milwaukee filmmaker Mark Borchardt’s attempts to complete an ambitious drama called Northwestern. Faced with money problems, Borchardt decides to finish a short horror film, Coven, which he hopes to sell as a means of financing the larger film. Alongside the productions, documentarians Chris Smith and Sarah Price depict Borchardt’s family life, friendships, and regular jobs as he tries to finish the films, get closer to achieving his dreams, and – crucially – hold all his shit together. It’s funny, sweet, sad, and strangely inspiring, not to mention a precise and generous depiction of my home state of Wisconsin. On the occasion of its twenty-fifth anniversary, here are some thoughts about American Movie and why it’s mattered so much to me over the years.

“No one has ever, ever paid admission to see an excuse.”

American Movie is fundamentally about the work of making movies, with Borchardt trying to pull his projects through obstacles both hilarious and heartbreaking. We see him at each stage, from early meetings where his enthusiasm is infectious to the painstaking process of final edits. We see him working with his cast and crew, several of whom have been involved with Borchardt’s projects for years and who applaud Mark’s perseverance even if they don’t always have confidence in his abilities. American Movie pays no greater attention to Borchardt’s big creative decisions than it does to the granular hassles of, say, convincing enough friends and family to clomp out in the snow to serve as extras. But Smith and Price don’t skimp on Borchardt’s larger process either, showing that – even in the often-humorous surroundings – Borchardt’s ambition is perhaps not as far ahead of his ability as some may assume. (In this respect, and others, the film proves an interesting comparison with Tim Burton’s Ed Wood, released just a few years earlier.)

We get only brief glimpses of what Northwestern might have been: abandoned black-and-white footage of a lanky Borchardt and other actors; a brief audition scene depicting an argument about a phone bill; and Borchardt working on the script by himself in his car. The talkative Borchardt describes his lofty vision of documenting the lives of characters who he describes as “Americans still fighting the west with a bottle of vodka in their hand,” in a clouded landscape of “dilapidated duplexes [and] worn trailer courts” where he hopes to consider their everyday dramas with empathy and nuance. I can’t say if Northwestern would’ve been a great or even good film. But one of the greatest accomplishments of American Movie is that it makes Borchardt’s dream project seem like it could have been just that. Maybe we’ll find out someday.

We get far more of Coven, which Borchardt insists is pronounced “coh-ven” because “coven sounds like ‘oven,’ man.” We see the film being rehearsed, shot, and edited; near the end of American Movie, we even see an abbreviated version of the finished product. Coven makes clear what’s hinted at in his talk of Northwestern or even the clips from Borchardt’s grimy early films: Borchardt is not an incapable filmmaker who, to some extent, knows what he’s doing. (One person to recognize this was Roger Ebert.) Borchardt cites The Seventh Seal and Manhattan as influences, even as he remains most influenced by horror classics Night of the Living Dead, Dawn of the Dead, and Texas Chainsaw Massacre, discussing them in a way that echoes their now-canonical status in the genre and the larger history of post-1950 cinema.

This isn’t the only way Borchardt seems ahead of his time. American Movie depicts a bridge point between the indie boom of the early ‘90s – which fueled the belief that aspiring filmmakers could break through telling idiosyncratic stories – and the digital-era democratization of film production in the twenty-first century. Borchardt (a cinephile at heart) still mostly uses old-school methods, but images of his friends and him working on his movies in his kitchen and bedroom are even more familiar now in the era of iPhones and editing software.

But American Movie is about other kinds of work, too. We spend almost as much time with Borchardt as he drives around delivering newspapers and works as a cemetery custodian. And, as much as he talks about his dreams and ideas for the life he wants, he also talks a lot about the life he doesn’t want and would refuse if given the choice.

“I don’t wanna end up being a nothing.”

American Movie is deeply concerned with class. In one evocative scene, Borchardt travels to a wealthy part of the Milwaukee suburbs. Standing outside the large houses, he first expresses his desire to make enough money to move to such a neighborhood, before quickly explaining that his house will be “less obnoxious” than these McMansions. There are many such moments in American Movie, where Borchardt simultaneously expresses his desire to move up the ladder (or just pay off his mounting debts, film-related and otherwise) while also declaiming any interest in compromising himself for the sake of a job or monetary success. This is a familiar dynamic (one found in the best country music, for example) and it animates American Movie as Borchardt tries to figure out who he is, who he wants to be, and what it’ll take to get there.

His money problems are real, and American Movie doesn’t shy away from them. Multiple scenes have him listing what he owes and to whom, and he keeps scrambling to finance Northwestern even as he’s in arrears with everyone from the IRS to child support to his dad. This is not a clichéd romantic portrayal of a starving artist or salt-of-the-earth struggle. It’s pretty clear that Borchardt’s not great with money, that his behavior has harmed his relationships, and that his priorities can slip easily from self-reliant to self-centered. He admits he’s refused work that he feels is beneath him, including blue-collar jobs that he might be qualified for and which helped build a stable working class. He notes with disdain that his father wanted him to become a security guard or truck driver, and he bemoans the fact that his new job feels more like a dead end than a new opportunity. Living in his parents’ home, a cozy space that bespeaks the Borchardts’ ability to gain a foothold, Mark rails against his seeming destiny in a way that mixes admirable defiance with clumsy projection. It’s a claim of alienation mixed with a kind of recognition, a dreamer running headlong into destiny.

This all bursts out (appropriately enough) at a Super Bowl party. As the Green Bay Packers seal their victory in the 1996 game, a drunk Borchardt turns nasty after his mother refuses to drive him to a bar to celebrate. Referring to the defeated New England Patriots, Mark looks into the camera and shouts that “every bitch-ass motherfuckin’ factory worker is gonna go down like that too.” Scolded by both mother and father, Borchardt adds “I will never be like you, you fuckin’ job-workin’ 40-hour motherfucker.” As Mark storms off to his room, Monica quietly assures the filmmakers (and perhaps herself) that he’ll be all right tomorrow when the beer wears off, before quickly pivoting back to her happiness at the Packers victory. Monica Borchardt isn’t given much space here or elsewhere to explore her own life and feelings, and maybe she cares not to share. But she’s clearly seen and experienced this before. Probably many times.

There’s a lot of alcohol in American Movie. Borchardt is seen drinking throughout much of the film (although not the last section), and his friend Mike Schank’s sobriety becomes something that Borchardt lovingly, if not always consistently, supports. For Borchardt, this drinking culture – all too recognizable to those of us from Wisconsin – anchors the larger experience that he wants to document in Northwestern. In the same scene where he tells an interviewer about “fighting the west,” for example, he adds that – for people like him and those he grew up with – there was no reliance on career plan or religious faith, but instead just “drinkin’, drinkin’, drinkin’.” Borchardt in American Movie becomes the character he describes from Northwestern, a merging of creator and subject that he recognizes in one of his post-bender moments of depression. Turning ruminative and rueful following a booze-soaked Thanksgiving, Borchardt processes his blues by working on a character in the Northwestern script. In the same scene, he thanks his friend Mike Schank for being there with him, as he so often is in the film. “I didn’t even want to wake up this morning,” he admits, but “Mike came over and put a smile on my face.”

“Hey Uncle Bill, thanks. Dad and Mom, man, thanks for all the sandwiches and the money. Mike Schank, you happy? Good, ‘cause don’t drink.”

As much as American Movie is about Mark Borchardt, it’s also about the people around him, especially those who (not always willingly) have been brought into his creative work. His parents and brothers hold a complicated place, with Monica particularly expressing both loving pride and the scars of a long and not always positive relationship. (Her final line – “He has a lot of dreams. I hope they come true.” – is quietly devastating.) There’s a suggestion of childhood turmoil, with Mark and his siblings discussing their parents’ fighting and how it may have affected him. His own three kids, from a previous relationship that is briefly and painfully depicted in the film, show up at several points and are even mustered into service to help with editing in an all-nighter that Borchardt gamely turns into a sleepover. (The fact that his eldest daughter Dawn is now a filmmaker herself gives these scenes extra sweetness.) And then there’s Uncle Bill, his dad’s brother who is helping finance Mark’s films and is also the relative with whom Mark seems to have the closest connection.

Uncle Bill is both blood and part of Borchardt’s chosen family, which proves even more important. Mike Schank is a loyal companion and stalwart collaborator, with a deadpan affect that never masks the sweetheart underneath. (Schank’s solo-guitar performances act as the film’s score, including a lovely, lonely version of “Mr. Bojangles” that is its main musical theme.) Another old friend, Ken Keen, is presented as both a good friend and bad influence, who it’s very easy to imagine Borchardt both relying on and getting in trouble with. The film tracks a new relationship with Joan Petrie, who enters as Coven’s production manager and both supports and challenges Borchardt at various points. Most of all, and best of all, is Uncle Bill.

The more I watch American Movie, the more I think Bill Borchardt is the most interesting and most important person in it. He’s the voice of healthy skepticism, waving at Mark’s grand plans with a dismissive “that’ll be the day” and worrying about his nephew’s plans for Bill’s money, which resides safely in the bank as Bill lives cheaply. But he’s also one of Mark’s greatest supporters, offering not only resources but encouragement both spoken and unspoken. There’s clear affection even in moments when Bill chides Mark or grows frustrated with him. (This leads to one of the film’s best scenes, when Bill is asked to re-record the opening line of Coven and grows increasingly exasperated over multiple takes. Out of Coven context, Bill’s increasingly frazzled reading of “It’s all right, it’s okay, there’s something to live for” feels like a kind of desperate mantra.)

Bill can be a vibe-killing sourpuss, but also a source of warm humor. Mark seems to understand and delight in his uncle’s curmudgeonly side: nearly every exchange involves Mark needling Bill to be more communicative or curious about what life has to offer, even at his advanced age. Bill mostly doesn’t reciprocate, but sometimes Mark finds a way through. I particularly love the scene of Bill in his trailer singing an original song for Mark, one of several he wrote about “what happened to me.” The song starts as a typical lament for lost love before Bill sings flatly about the woman’s death, and the fact that he’ll “visit your grave every day” before hilariously correcting to “well, not every day, but I’ll visit it sometimes if I ever find it.” As Bill sings this odd ballad, there’s a shot of Mark looking at his uncle with the purest expression of love in the entire film. And then the scene fades out, with Bill playfully scatting “doodley-do” as they head out into the cold.

They’re heading to Thanksgiving, where Mark gathers with his chosen family – Joan, Mike, Ken, and Bill – while his parents, brothers, and kids are notably absent. The scene contains a moment of astonishing tenderness, as Mark helps Bill take a bath. Filmed through a partially open bathroom door, the two men tease each other, helped no doubt by the peppermint schnapps Bill enjoys while bathing, and Mark cares for his uncle with an easy intimacy. After dinner, both drunk, Mark and Bill hunker down in the living room where Bill deflates Mark’s latest pronouncement about cinema by replying “cinnamon?” And then they start giggling.

Their bond comes through even more strongly in the film’s final scene. Sitting outside Bill’s trailer, Mark tries to talk him up about the possibilities of Northwestern and starts pontificating again about the American dream. Bill ignores him, noting under his breath that it’s past time for his dinner before raising his head and delivering a closing speech, with words that serve as both heartfelt blessing and stern advice. His final line (delivered just before a text crawl notifying us of his death soon afterwards) serves as a benediction: “Make everybody happy. Be a comedian.”

“Make everybody happy. Be a comedian.”

American Movie is really funny. Many lines – whether famous, like the “coven”/“oven” thing, or less well-known, like Monica’s “maybe he plays the five-dollar ones” (trust me, it’s hilarious) – seem crafted by comedy writers in both structure and execution. A few scenes, like the one where Mark repeatedly tries (and fails) to put an actor’s head through an improperly scored cabinet door, play like classic comedy setups. The film’s broad-stroke personalities (grumpy Uncle Bill, gentle goofball Mike) embody well-worn comedic character types. And, even though it has both dark moments and a melancholy tone, American Movie has made me laugh harder over the years than almost any other film.

I’ve wondered sometimes if I’m laughing at this crew rather than with them, or even about them in a way that avoids finger-pointing mockery. This tension is something that seems to define some aspects of the film’s larger popularity, as well, especially as Mark and Mike became internet-era celebrities. (The filmmakers, to their credit, mostly avoid encouraging such gawk either in the film or how they talk about it.) It’s one of the main reasons why your mileage may vary on American Movie, and even my own has varied over the years. When I was younger, I’m sure I used to respond more mockingly than I do now, which I’ll chalk up less to learned maturity and more to realizing how much closer these folks are to me in ways that I didn’t always appreciate. I still sometimes wonder if my enjoyment of American Movie isn’t based at least in part of my own weird projections or distancing. It’s impossible to know for sure, I guess, and I’m not even sure it’s possible to make such easy distinctions. But I still find this movie hilarious, and - after spending so much time with American Movie - I’m pretty convinced me that these guys are in on the joke.

It isn’t just about the zingy nature of so many lines – “there’s dialogue here that would make the Pope weep” – or the sharp timing of reactions that bespeaks the participants’ familiarity and rapport. It’s not just about the fact that Mark, Bill, Monica, and the rest are clearly intelligent people, with a layered understanding of themselves and their world. It’s also about the fact that they all clearly understand that they’re performing here, offering a version of themselves that sometimes leans into their silly side or plays it against the other parts of their personae. To me, the clearest tell comes in the scene where Mark, his parents, and Uncle Bill go out to lunch for Bill’s birthday. After a voiceover discussing how Mark’s father always admired his older brother, Bill looks at the camera and dryly offers the following bit of wisdom: “nice day if it doesn’t rain.” The camera stays on him, and Mark next to him, as both begin to chuckle.

“These are the vistas right here…There’s lonely roads, but there’s warm houses and cars.”

I’m almost positive that I’ve heard people in Wisconsin say “nice day if it doesn’t rain.” I’ve probably said it myself. Indeed, I’ve never seen a better depiction of my home state than American Movie. Part of it is the same reason why Mark saw potential in Northwestern: this film makes Wisconsin’s weather into a character, from the sky that Mark describes as the “umbrella of gray over you,” to the varying levels of snow that line streets and sidewalks, to the chilly air evoked by bundled-up coats and hot puffs of forced air, to the gleaming, liberating sun of spring and summer. The changing seasons mark time passing before anyone speaks a line or reveals a new development, like when they return to the same stretch of woods in three consecutive seasons, all in the hopes of capturing another small piece of Coven. It’s only in the summer that they finally get the film done, and the sunset over the triumphant final screening glows with the hazy calm of the fleeting season. (At one point, it frames Uncle Bill like a halo.)

More than the landscape, though, American Movie exudes much of the culture that I recognize with fondness. There’s the dry understatement of the humor, especially in Uncle Bill’s comments and even the muffled resonance of his voice. There’s the seeming stoicism that barely hides a backstory that isn’t spoken and doesn’t need to be, like when Monica concludes about Mark’s tangled relationship with his ex that “There’s nothing that lasts. But I think this will last for a long time.” There’s the way that excitement and concern get expressed through the same guarded observations. There’s the grudging commitment to work as a symbol of both one’s pride and one’s regrets: “I been out here three fuckin’ times now, man,” Mark admits of one attempted scene, “doing the same shit.” There’s the repressed emotion in monosyllabic interjections like “mmm” and “oh,” and the boiling over into moments of explosive catharsis. There’s all the beer, and the way it both creates community and alienates people from each other. (Not to mention from themselves.) And, on top of all that, there’s the single most Wisconsin moment ever captured on film: Mark turns to his mother as they trudge out in the woods to record some audio and says, with offhand exasperation, “Hey, how the hell far away is this marsh now?”

But what most reminds me of Wisconsin, or at least my Wisconsin, and why I usually recommend American Movie on those terms, is because of the way that it engages with the state’s people without turning them into exotic clichés. The folks in American Movie feel like real people, for both better and worse. Their accents and clothes and turns of phrase (which all warm my heart as a Badger State boy now living elsewhere) don’t turn them into a gloss of “ya hey” cornpone or hardscrabble lives on the frozen tundra. I’m not from the Milwaukee area, so perhaps it reads differently on a local level in a city with its own distinct and important stories, but American Movie stands atop a very short list of films that I consider worthy depictions of where I’m from.

At the same time, it’s not just a regional thing. I reckon that American Movie is a whole lot smarter and more profound than, say, the similarly named American Beauty, released the same year to acclaim and success and now rightfully forgotten. And it’s way the hell more entertaining. So, here’s to a great film. Here’s to a Wisconsin that I love and miss. And here’s to us all following Bill Borchardt’s advice to make everybody happy. I’m not sure it’ll work, but it’s sure as hell worth a try.

PS - Mark Borchardt is still making movies - you can check out what he’s up to here.

If you like what you’re reading here, please think of subscribing to No Fences Review! It’s free for now, although we will be adding a paid tier with exclusive content soon. Also, if you’d like to support our work now, you can hit the blue “Pledge” button on the top-right of your screen to pledge your support now, at either monthly, yearly, or founding-member rates. You’ll be billed when we add the paid option. Thanks!