Kris Kristofferson died late last month, at 88. You don’t need anyone to tell you that he was one of the most distinctive, consequential songwriters ever—a major figure in country music, of course, but also in that rock sub-genre he helped to invent, “singer-songwriter.” His influence, though, while massive, is often a little misapprehended, I think. It would be nearly impossible to cite a country-leaning songwriter in this century’s Americana scene who wouldn’t point to Kristofferson as a lodestar. His transformative influence on the country music mainstream of the past fifty years is fuzzier. As a songwriter, Kris Kristofferson was an inspiration to Nashville but rarely a model.

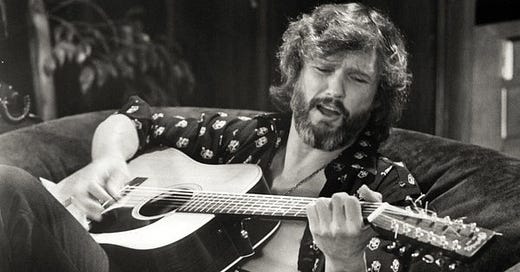

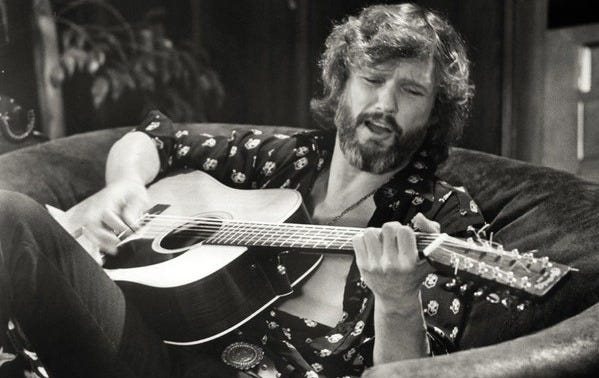

After he became a star, and particularly after he became a movie star, Kristofferson helped bring a new sexy masculinity to the genre, sensitive and chatty rather than strong and silent. He was a proto-Outlaw, importing elements of the Sixty’s counterculture to Nashville (the do-your-own-thing, individualist kind, I mean, not the collective variety) while encouraging so many of his peers to pull on some jeans, grow a scraggly beard and loosen up a little. In a 1975 column in Country Music, journalist Paul Hemphill noted that “one of Nashville’s more traumatic moments came some four years ago” when Kristofferson, “wearing shoulder-length hair and a scruffy suede suit,” had “floated to the stage” of the CMAs to collect his Best Country Song prize. Point being that, in ‘75, he wasn’t standing out any longer.

The dozen or so songs that made Kristofferson’s reputation as an artist—most of them included on his 1970 self-titled debut album, most of the rest on his 1971 follow-up, The Silver Tongued Devil and I—were admired almost out of the gate. And they remain revelatory, both to anyone encountering them for the first time and to those of us fortunate enough to have encountered them for most of our lives.

It took him a minute, though, before he reached the masterpiece phase of his career. He’d enlisted in the Army, then passed on an assignment to teach English literature to West Point cadets. He wanted to become a songwriter instead, like heroes Hank Williams and Bob Dylan. Given these diverging career paths, his first real songwriting success after moving to Music City seemed to find him struggling to have it both ways: “Viet Nam Blues,” a Dylanesque talking blues slamming antiwar demonstrators, became a #12 hit in 1966 for trucker-anthem specialist Dave Dudley. He landed a few more cuts in the next year or so: Johnny Darrell’s “Don’t Tell My Little Girl”; Charlie Louvin’s “Perfect Stranger”; and Buddy Cagle’s “To a House from a Home,” in which Kristofferson’s lyric, a la Willie’s “Hello Walls,” is addressed to the title structure. There were a few more cuts, too, but no hits to speak of.

In 1968 molasses-voiced crooner Roy Drusky became Kristofferson’s first all-in early adopter. Drusky’s album Jody and the Kid featured the Kristofferson-penned title track; a first stab at themes he’d later nail in “Me and Bobby McGee” called “When I Loved Her”; and “Shadows of Her Mind,” a ballad that previewed the poetic tone of lyrics to come:

In the mornin' as I wakened with the dawn / Without warnin' I could feel that she was gone / Leavin' nothin' but her silence next to me...

1969 was the breakthrough. Kristofferson songs were cut at least a dozen times that year, including some real country radio successes: “Me and Bobby McGee” was a #12 hit for Roger Miller; “From the Bottle to the Bottom” went Top 20 for Billy Walker; and “Your Time’s Comin,” a cowrite with Shel Silverstein, climbed all the way to #4 for Faron Young. Kristofferson was a professional songwriter now. His days of emptying trash bins at Columbia or piloting helicopters to oil rigs in the Gulf were forever in the rearview. But these successes, however validating they must have been, were nothing compared to what followed.

In terms of commerce and art, in quantity and quality, Kris Kristofferson’s 1970 has to be in the running for the most successful year a songwriter has ever enjoyed. I’ll just list them:

“Once More with Feeling,” recorded by Jerry Lee Lewis, was another Kristofferson/Silverstein cowrite. It debuted on the country charts in February on its way to #2.

“The Taker,” by Kris and Shel again, became a #5 country hit for Waylon Jennings. It also cracked the Hot 100.

“For the Good Times,” became Ray Price’s signature song, topping the country charts and climbing to #11 pop just after Labor Day.

“Sunday Morning Coming Down,” became a country #1 and pop #46 a month later for friend and supporter Johnny Cash.

“Help Me Make It through the Night” charted in December for another close FOK, Sammi Smith, on its way to topping the country charts and climbing to #8 pop early in 1971.

Once Price, Cash and Smith scored those giant countrypolitan crossovers, Nashville embraced Kristofferson’s songbook with gusto. “Help Me Make It through the Night,” just for one example, was cut by at least 50 different mainstream country singers in 1971 and ‘72 alone. Another couple dozen versions of the song were cut by pop and soul artists during that same stretch. Very quickly, in just two or three years, a handful of Kristofferson songs had already been recorded literally hundreds of times. His songs became so well known, so quickly, that they were parodied for country fans in real time. Country clown Ben Colder released “Help Me Fake It through the Night” and “Sunday Mornin’ Fallin’ Down” while the great Homer & Jethro cut “Fer the Good Times” and “We Didn’t Make It through the Night.” Nashville cat producer/guitarist Jerry Kennedy even released an instrumental tribute album.

Nothing succeeds like success, and Nashville loves to go all in on a commercial trend. Yet, as it turned out, Nashville didn’t suddenly start cranking out a bunch of songs that sounded like Kristofferson must’ve written them. Kristofferson’s moody melodies, his crowded lyric sheets, and his unhurried tempos were rarely emulated directly by other country singer-songwriters. Why? I sometimes wonder if Kristofferson’s singularity wasn’t a happy consequence of his serious limitations as a vocalist, limitations that most other writers never had to learn to live within or to work around. The murmured melodies of his best numbers are lovely and memorable but notably undynamic, even a little claustrophobic. Part of Kristofferson’s genius, it seems, is that his vocal constraints contributed to a defining feature of his songwriting style. His cramped vocal range builds an intimacy into his tunes before the words even register. Kristofferson was one of one.

That is not at all to say he wasn’t tremendously influential. While his peers mostly avoided copying his circumscribed melodies, they ran with his expansion of what a country act might sing or write about. The sexual frankness in some Kristofferson songs cleared space for later country hits like “Easy Loving,” “Behind Closed Doors” and “You’ve Never Been This Far Before,” just for starters, but it’s not like those singles’ hooky melodies were ever going to be confused for a Kristofferson composition along the lines of his “I’ve Got to Have You.” Sammi Smith had an intensely sensual hit with that one in 1972.

Rhodes scholar Kristofferson was often a self-consciously literate songwriter in a way that was new to guitar pulls around town. I’m not a big fan of songs like “Darby’s Castle” or “Duvalier’s Dream,” but will concede they aren’t anything like what Harlan Howard, Dallas Frazier, or even Willie Nelson would’ve ever written. His “Best of All Possible Worlds,” which I love, is clearly written by, and for, someone who did the reading in Western Civ. He deployed irony in ways that were new to country circles as well. While collaborator Shel Silverstein and future fellow Highwaymen Willie, Waylon and Johnny would do that themselves sometimes for laughs, Kristofferson stayed sober. His “Blame It on the Stones” isn’t funny because he’s trying too hard to be funny. His “The Law Is for Protection of the People” is not funny because it’s true.

His biggest impact came from his preferred themes and subjects. The era and his smarts, combined with his comparatively privileged background, found him attracted to existential questions and crises that other country songwriters, before and since, have mostly avoided. (There were exceptions: Merle, I am looking in your direction…) Like so many of his early songs, “Me and Bobby McGee” isn’t interested in the material conditions standard to country songwriting, like child rearing or bills that pile up. What pops in the song is that “freedom’s just another word for nothing left to lose,” a line only bumper sticker deep but that, like all great bumper stickers, captures something that rides shotgun with you down the road. A more traditional country songwriter would never have gone there. Indeed, Kristofferson was advised by songwriting pals to cut the philosophy and double down on the specifics of the relationship and its end, as they prompted the story song in the first place. But Kris, bigger issues on his mind, only waves at such details: “Somewhere near Salinas, Lord, I let her slip away…”

When I hear Janis Joplin shouting “Bobby McGee” at a bar or coming from a car on the street, I first think, “Oh, God, not this again.” Then, sure enough, Joplin’s explosion of Kris’ compact melody pulls me in and… we’re off! “I’d trade all of my tomorrows for a single yesterday.” I don’t feel that way when I hear any of Kristofferson’s several recorded performances of the song. The conventional wisdom—which I will push back on in a moment, just a bit—has long been that, as a singer, Kristofferson made a great songwriter. If you enjoy reading brutal critical assessments, then reviews of early Kris Kristofferson albums are probably your jam. The most infamous comes from Robert Christgau, who, upon hearing 1970’s Kris Kristofferson, judged him “the worst singer I've ever heard. It's not that he's off key—he has no relation to key. He also has no phrasing, no dynamics, no energy, no authority, no dramatic ability, and no control of the top two-thirds of his six-note range…” Veteran country journalist Bob Allen once described Kristofferson as “a singer whose gruff, nonchalant singing style verges on tone-deaf” while founding-father country critic John Morthland declared that “every good song he’s ever written has been done a zillion times better by someone else.” And so on and so on.

(Even my wife got in on the action. At a 2011 Kansas City concert with Merle Haggard and the Strangers, Kris apologized several times for the ill effects of the head cold he was getting over. Doris leaned over to me and whispered: “Just how long has he been sick?”)

A few caveats are in order. First, these criticisms are spot on—except when they aren’t. His recording of “Why Me,” where Kristofferson prostrates himself before amazing grace and sounds like he’s an answering an altar call on his hands and knees, is a zillion times better than any other version precisely because of its singer’s oh-so-humble instrument. Every one of his several bedraggled recordings of “To Beat the Devil” beats everyone else’s recording of the song. Second, even while wrestling unsuccessfully with the key or mangling his phrasing, Kristofferson still somehow possessed a soulfulness and emotional presence that could be riveting. His voice typically conveyed a kind of wisdom, too—an effect every bit as performative as any other quality a more technically assured singer might possess. The version of “Sunday Morning Coming Down” off his debut is ostensibly about someone in spiritual crisis but feels at least as sage as desperate.

Finally, and this is very important, he got better. As he aged out of singer-songwriter mode and more into what I’d just call his troubadour era, he made the best albums of his career. Working with producer Don Was for 2006’s This Old Road, 2009’s Closer to the Bone and 2012’s Feeling Mortal, and with co-producers Shawn Camp and Tamara Saviano for 2016’s The Cedar Creek Sessions, he never sounded better. There were several reasons for this. The settings for all these sessions were mostly very spare, either just guitar-and-voice or a small combo, which means Kristofferson wasn’t competing with an arrangement the way he’d often had to do throughout his career. He was able to sing softly, conversationally, instead of having to rock out. The new songs were not going to be recorded hundreds of times, but they were smart, sturdy, and heartfelt, their subjects smaller and more personal, which helped too. He was an old friend at ease, talking to himself. We were lucky eavesdroppers.

Mostly, I think Kristofferson simply grew into his instrument. His crusty voice didn’t improve with the decades, but it didn’t fall off either and the actor in him had learned how better to exploit all the gravel. To borrow a line from one of his better late songs, “Pilgrim’s Progress,” he had perfected himself in his own peculiar way. One of one.

If you like what you’re reading here, please think of subscribing to No Fences Review! It’s free for now, although we will be adding a paid tier with exclusive content soon. Also, if you’d like to support our work now, you can hit the blue “Pledge” button on the top-right of your screen to pledge your support now, at either monthly, yearly, or founding-member rates. You’ll be billed when we add the paid option. Thanks!

I'm right there with you with the Don Was and Saviano/Camp albums. I'll add the Austin Sessions in there, too, for, I feel, a more grown-into voice on his evergreens.

Excellent. I swear by his live record BROKEN FREEDOM SONG.